Whether we realize it or not, the invasion of technology into our essential human experiences is proceeding at a dizzying pace. With the advent of Artificial Intelligence, the phenomenon is headed for exponential growth.

Whether the aim is to create children with certain traits, erase sex differences, or use AI agents to take the place of real companions, scientific “advances” are fundamentally changing how we live and relate to one another. The very fabric of our human ecology is being rewoven in a million labs and boardrooms across the world. Some of the results promise to be disastrous.

As a society, we desperately need an examination of the proper use of technology. But we should not expect the techno-optimists gleefully running the experiment to stop and consider the immense implications of their work. No, this may be up to the Catholic Church, with her long tradition of reminding men and women of moral, ethical, and theological truths as they rush pell-mell down the exciting branching roads of history.

To ponder man’s relationship with technology is to ponder his essential nature, since the use of tools is an inextricably human trait. To be human is to navigate our environment tool in hand, whether that tool is a honed ax or a scientific calculator. When are we using tools properly (preventing childhood diseases) or monstrously (producing and destroying our own children in labs)? One intelligent guide was provided by Pope Francis in his encyclical on the environment.

In “Laudato Si’ ” (“Praise Be to You”), Pope Francis warned of falling into a worldview he called the “technocratic paradigm” in which technological achievements take priority over all else. You can see the tendency at work, among the techno-optimists and their sponsors, who approach problems without recognizing any moral constraints, ignoring deeper spiritual and social dimensions.

To them, technology is a universal solution and nature something to be mastered. Their aim is a future in which man’s dominion over his environment will be complete.

This unhinged anthropocentrism has grave implications. It promotes the exploitation of nature over responsible stewardship of God’s creation, fostering a “throwaway culture” that discards people and resources.

It puts technology at the service of the individual human will’s drive for pleasure, power, and profit, instead of at the service of the common good. It treats living beings as “mere objects” subject to “unrestrained manipulation,” making of human life a product instead of a priceless gift. It creates a utilitarian hellscape, in which societal ideals are valued more highly than persons. It marginalizes the vulnerable, crushes the poor who can’t access its benefits, and destroys solidarity by prioritizing individual autonomy.

The central mistake here is getting the purpose of technology wrong. When a man picks up an ax he must wield it responsibly, ethically, and morally. The same goes for his AI agent generator or the hormones that he uses to modify the bodies of adolescents. He must respect the natural limits that keep us personally and as a species flourishing, connected, rooted, and healthy, even when the limits seem to chafe our will.

In other words, he must preserve what Pope Francis called “integral ecology,” which is “inseparable from the common good.” The common good being “the sum of those conditions of social life that allow social groups and their individual members … thorough and ready access to their own fulfillment.”

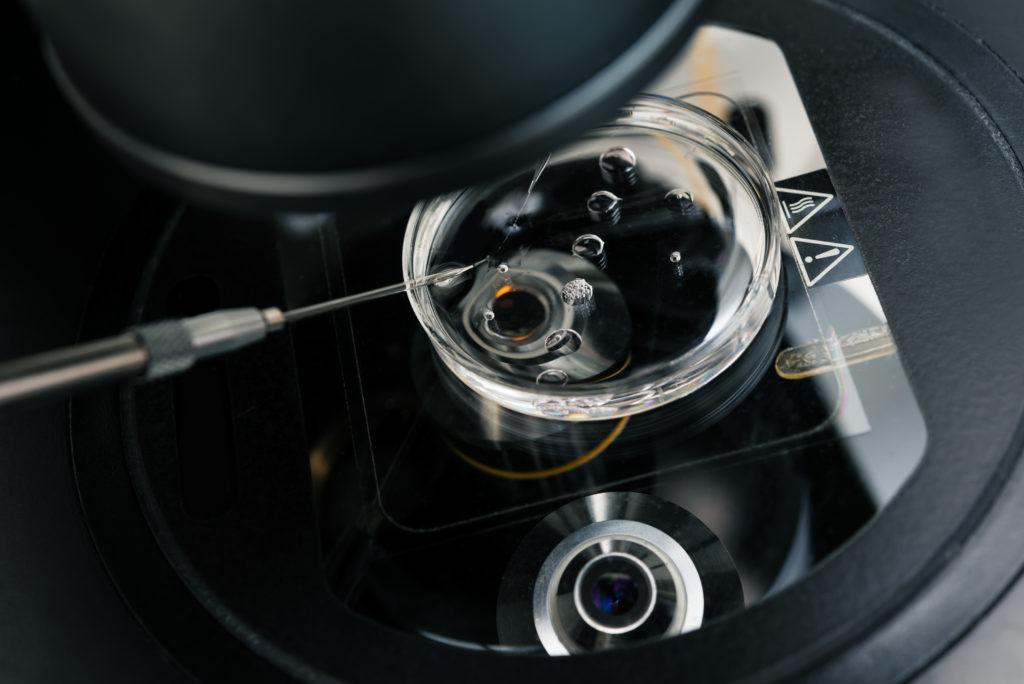

It helps to apply these concepts to something relatively simple: the creation and selection of embryos. The couple that longs for a child and is dazzled by the temptation to pick the embryo that best fits their expectations will have trouble denying themselves that technology.

But these practices gravely violate an integral ecology. They disrupt the natural order by turning a sacred act tied to the marital union (procreation) into a lab procedure, and children into products. The consumerist frenzy around IVF (U.S. annual revenues over $5 billion and rising) encourages young women to put off childbearing in favor of a technological “rescue” later in life.

Expensive embryo selection will reserve “enhanced” offspring to the wealthy, creating a genetic divide between the rich and poor. It will produce a culture in which only certain traits are valued, marginalizing those who opt out or can’t afford access. In a world in which the rich make “perfect” babies in a lab, what will society’s tolerance be for the disabled children born to poor parents? Will charity and patience survive?

The future is here already, about to burst out of a lab in Palo Alto and already transforming your children’s experience at school or online. Who will tell them — and remind us — that God gave us our technological abilities so that we could fulfill his divine plan, not make up our own plans as we go along?

Inventions and innovations should be oriented to the common good that Pope Francis talked about. If we heed his advice, the future might just look more like God’s kingdom than the fever dreams of a fallen and weak humanity.