ROME — To be honest, Synods of Bishops in the Vatican aren’t generally the stuff of high drama. Participants are often selected because they support the agenda of the pontiff who convened the meeting, and synod staff are generally adept at guiding things toward the desired conclusions.

Yet because these affairs involve human beings, many of whom, to be clear, are alpha personalities accustomed to doing things their way, there are always surprises along the way, and that’s certainly true at the midway point of the Oct. 6-27 Synod of Bishops for the Pan-Amazon region in the Vatican.

Herewith, a sampling of noteworthy twists and turns.

First, it’s striking that at a Synod of Bishops, at least in the early stages, most of the stars of the show haven’t been prelates at all. In fact, you could make the argument that the two figures who’ve made the deepest impression aren’t even human.

That’s because the most memorable moment so far remains something that actually happened two days before the synod’s formal opening.

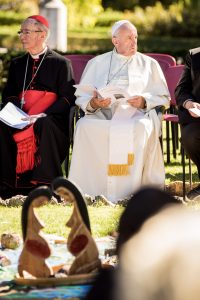

On Oct. 4, the feast of St. Francis of Assisi, the pope participated in an indigenous ceremony in the Vatican gardens in which people knelt and prayed before two images of semi-naked pregnant women, causing no small amount of consternation in traditionalist Catholic circles who suspected some sort of pagan ritual.

Two weeks later, Vatican spokesmen were still attempting to put out the fire.

Paolo Ruffini, the Vatican’s communications czar, told reporters Oct. 16 that he took the statues to simply be representations of life with no special spiritual significance, and that “looking for pagan symbols is seeking evil where there’s no evil.”

Beyond that minifracas, participants in the synod will tell you that the speeches which have stirred the most reaction have come from the representatives of the roughly 400 indigenous communities in the Amazon rainforest.

Other protagonists at the Vatican’s daily briefings have included luminaries from outside the Catholic Church, such as the U.N.’s Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Victoria Lucia Tauli-Corpuz, (and a non-Catholic, whose father is an Anglican priest), and Brazilian scientist Carlos Afonso Nobre, who won the 2007 Nobel Prize for his work on the IPCC report on climate change.

In all, there are just about 170 bishops among the full body of roughly 260 synod participants, suggesting this is less a synod “of” bishops than a meeting “with” bishops.

For a second surprise, despite early attempts to project strong consensus, it’s become clear there is actually disagreement on at least one point: the ordination of married men to solve priest shortages in isolated rural communities in the Amazon.

The synod began with its relator, or chairman, Brazilian Cardinal Cláudio Hummes, putting the married priests debate squarely on the table, saying the request came from many indigenous communities during the consultation phase.

At an early news briefing, Brazilian Bishop Erwin Kräutler said “two-thirds” of the prelates in the hall are favorable to ordaining the so-called “viri probati,” meaning tested married men.

Yet as things have unfolded, some discordant notes have been struck.

At an Oct. 16 briefing, for instance, Bishop Wellington Tadeu de Queiroz Vieira of Cristalândia in Brazil said that in his opinion, the problem with attracting new priests in the Amazon isn’t the celibacy requirement but scandals and poor behavior by some priests, so the antidote isn’t marriage but deeper holiness.

Queiroz also claimed to not be alone in feeling that way: “I think there are many who share my views,” he said.

It remains to be seen how the synod will handle the issue in its concluding document, but there seemed to be a growing sense at the halfway point that “specific problems,” such as the married priests debate, shouldn’t mar a broad consensus on other matters.

It’s noteworthy that despite being a synod about the Amazon, many of the loudest voices in and around it aren’t native to the Amazon.

For example, there have been complaints from women’s activist groups about the fact that no women have the right to vote in the synod, with the public faces of those complaints coming mostly from Europe and North America.

A news conference at Rome’s Foreign Press Club just before the synod, staged by a group called Voices of Faith, featured a strong turnout of nuns from a convent in Switzerland, but no actual Amazonians.

Meanwhile, several counterevents organized by more conservative and traditionalist groups have featured well-known pundits from Italy, the United States, and other first-world settings, but few figures from the Amazon itself.

Even inside the synod, it’s often striking how many of the bishops and other figures playing lead roles are foreign missionaries, descendants of foreign-born ancestors with roots in Europe, or who’ve had their formation and studies in Europe.

Bishop Carlo Verzeletti of Castanhal, Brazil, who’s spoken in favor of married priests, was actually born in Trenzano, Italy, in 1950, and was ordained in Brescia before going to the Amazon as a Donum Fidei priest in 1982. Kräutler himself was born in Austria and headed to Brazil as a missionary in 1965, the year the Second Vatican Council ended.

Bishop Eugenio Coter of Pando, Brazil, who’s spoken in favor of deeper inculturation and giving an “Amazonian” face to the liturgy, was born in 1957 in Brescia in Italy, the home region of St. Pope John XXIII.

In other words, the Synod on the Amazon is another case in which the local and the universal are colliding, with results yet to be determined.

No matter how the synod ends, it won’t be the final word. A synod is merely an advisory exercise, so everything depends on what Pope Francis decides to do with what he hears, and given this maverick pope’s reputation for upsetting the apple cart, that may be a prescription for more, and bigger, surprises still to come.