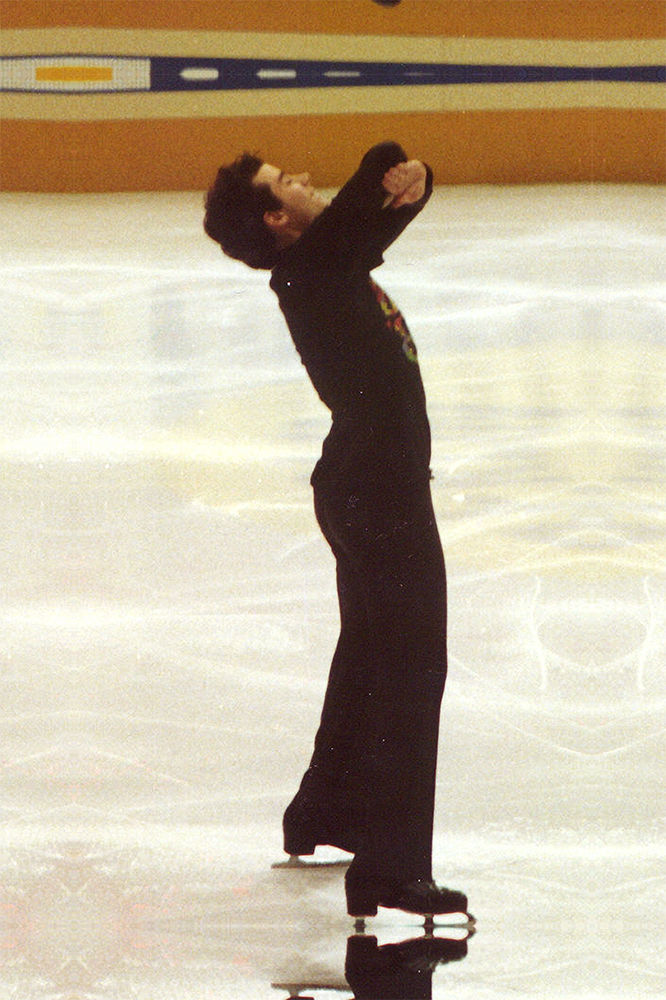

Christopher Bowman (1967-2008) was a flamboyant, profoundly talented figure skater from Southern California who blazed bright, burned out fast and died young.

He was known during his brief career as Bowman the Showman. His drinking, drug use and erratic, unpredictable behavior infuriated and perplexed his coaches, family and fans.

His left bicep bore a tattoo of a pitchfork-brandishing red devil with the caption: “Nobody’s perfect.”

And to watch him, even on grainy 1980s Youtube videos, is to be transported.

Born in Hollywood to parents Joyce and Nelson Bowman, he was a professional model as a baby and did commercials and TV shows as a child.

He won the World Junior Championship at the age of 15. He was also a two-time U.S. National Champion and a two-time World Medalist (silver in 1989, bronze in 1990). He won 7th place in the 1988 Olympic Winter Games and placed 4th in 1992.

You don’t have to know anything about skating — which I don’t — to involuntarily grin the second he came onto the ice. You don’t have to be a judge to know that his insouciant joy, his wild-card choreography and his courage were in a class to themselves.

He flirted, blew kisses, swiveled his hips, mugged — and, somehow, got away with it. He made a triple lutz-triple toe loop look like the result of a carefree afternoon’s work. Even skating to the cheesy “Wooly Bully” by Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs at the 1989 World’s Exhibition, he was indescribably charismatic.

At the 1990 U.S. Championships he botched two jump combinations and improvised the last two minutes of his long program, which in the skating world is apparently unheard of. He explained afterwards: “I had an attack, a strategy, the heart, soul and aggressiveness to challenge.” He won the bronze, but he and Frank Carroll, his coach of 18 years, parted ways as a result.

His counterparts were perhaps not so much skaters as bullfighters, tightrope-walkers: the gypsy flamenco dancer Carmen Amaya, of whom blogger KeriLynn Engel wrote: “In Spanish culture, and especially in flamenco, there is a word called duende, usually translated as spirit, soul or fire. It is a difficult concept to translate, but it is meant to convey the heart, soul and emotion of flamenco. Different styles of flamenco dancing convey different emotions, but they all have duende. As a folk music, flamenco embodies the hopes, joys and sorrows of the Romani people, and expressing this in dance is duende.”

Meanwhile, Bowman’s personal life was a mess. In “Inside Edge: A Revealing Journey into the Secret World of Figure Skating” by Christine Brennan, the chapter on Bowman is entitled, “The Great Wasted Talent.” Toller Cranston, the former skater who briefly coached Bowman — and very unwisely allowed him to move into his Toronto apartment — entitles his relevant chapter “The Electric Chair.” Bowman later admitted that from 1987 to 1992, he had a $950 a day cocaine habit.

In 1992, he retired from competition. He skated, briefly, for the Ice Capades. He gained weight. He became homeless, cleaned up, got married and fathered a daughter, started coaching, first in Massachusetts, then Detroit. On an “Inside Edition” episode aired in 1998, he spoke of the women, the drugs, the arrests. “I want to have a good time. I want to be the Hans Brinker from hell. But I don’t want to wind up dead.”

He was found in a North Hills Budget Inn on Jan. 10, 2008, gone at the age of 40 from what was ruled an accidental drug overdose.

I don’t subscribe to the notion that drugs fuel creativity. For the addict, they dull creativity and, eventually, one way or the other, snuff out the soul. But I do think that the artist, the athlete and the addict are alike —driven by a hunger for transcendence.

Perhaps that is why so many outsize talents in music, art and sports die so young. Perhaps such charisma, such “duende,” such hunger, are too much for certain mere mortals to contain.

Upon hearing of Bowman’s death, former coach Frank Carroll observed: “It’s such a helpless feeling, when everything you think you’ve done has done nothing in the long run.”

But to say that just because Bowman died young he was a “wasted” talent — and that the efforts of those who loved him amounted to nothing in the long run — I can’t subscribe to either.

To watch his Men’s Free Skate program in the 1989 U.S. Championship, especially knowing of his inner struggles at the time, is to witness humanity at its near best.

That’s not to romanticize bad behavior or addiction; it’s to acknowledge that Christopher Bowman paid the price. It’s to thank him, and all who supported him, for what he achieved: a little epiphany of a star eternally shooting, twirling, jumping across the skating field of the cosmos.

Heather King is a blogger, speaker and the author of several books.

Interested in more? Subscribe to Angelus News to get daily articles sent to your inbox.