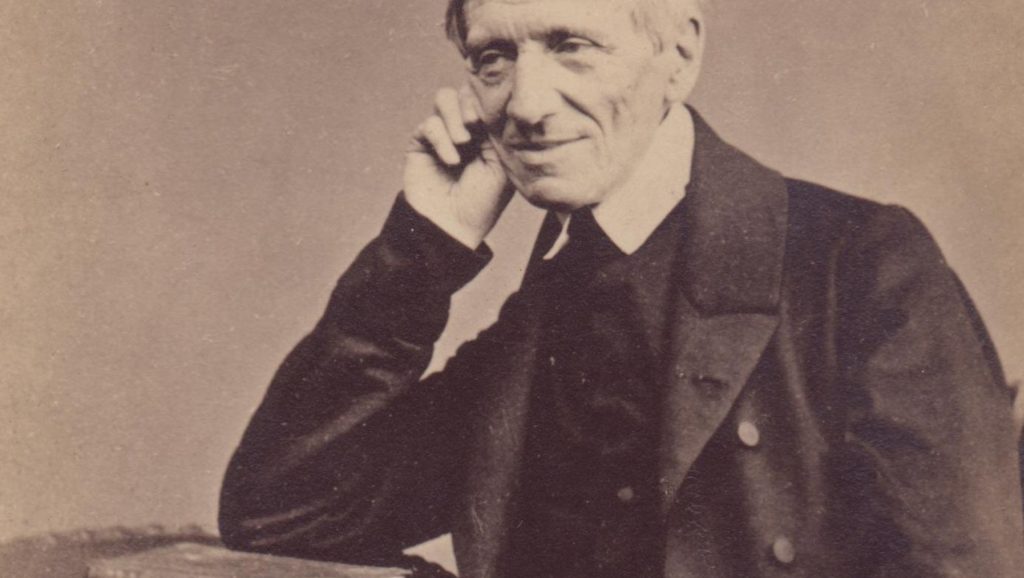

Lately I’ve read two books by St. John Henry Newman. One is Newman’s first novel, “Loss and Gain,” while the other is that classic “history of my religious opinions” (Newman’s words), the “Apologia Pro Vita Sua.” Although the two volumes could hardly be more unalike in most respects, both are of considerable interest for what they tell us about the process of religious conversion.

Let’s start with “Loss and Gain.” Published in 1848, just two years after Newman’s own conversion, its central character is an Oxford student named Charles Reding whose religious journey, from Anglicanism to Catholicism, parallels Newman’s. The story is by no means autobiographical — Reding isn’t Newman by another name — but the process of conversion is much the same in both cases.

Both conversions, the one in the story and Newman’s in real life, are what might be called Oxford conversions. Reding’s occurs in the heyday of the Oxford Movement, the Anglican renewal effort that sought to make English Anglicanism more Catholic, and ended — for those like Newman who, after much prayer and study, finally took the step of “crossing the Tiber” and became Catholics themselves.

And the key to conversion? Above all God’s grace of course, but, paradoxically, in human terms the key is often the objections raised by others against what is for Reding, as it was for Newman, no easy decision. Time and again this obstacle moves the young man to persist even though persisting means breaking with family and friends and even his beloved Oxford.

On the morning of his final parting, Reding bids an intensely personal goodbye to the university, described in lyrical terms. “The morning was frosty, and there was a mist; the leaves flitted about; all was in unison with the state of his feelings. … There was no one to see him; he threw his arms round the willows so dear to him, and kissed them; he tore off some of their black leaves and put them in his bosom.”

In the case of the “Apologia Pro Vita Sua,” the spur lay in the very circumstance that led to the book (“How great a trial it is to me to write the following history of myself,” Newman writes at the start). The story is familiar. An Anglican clergyman and popular writer named Charles Kingsley took an unprovoked cheap shot in a journal review at Newman and Catholic priests generally, alleging something very like habitual untruthfulness on their part.

Newman demanded a public apology, Kingsley hedged, and the upshot was a series of pamphlets by Newman putting the whole episode on the record. The pamphlets were the basis for what became the Apologia.

The book is not an easy read, since it assumes a familiarity with religious language that comparatively few readers today possess. But it contains memorable writing, such as this on the Catholic Church — an assembly of vastly different individuals “brought together as if into some moral factory, for the melting, refining, and moulding, by an incessant, noisy process, of the raw material of human nature, so excellent, so dangerous, so capable of divine purposes.”

These two books together point to a surprising conclusion: Often, as here, despite significant opposition, someone persists in a life-changing decision at least partly because the opposition has the unanticipated consequence of reinforcing the determination to persist. Although that may seem like a banal conclusion, in the hands of a master like Newman it sheds helpful light on what might otherwise look like incomprehensible stubbornness.