Who still reads poetry? In a digital age and in a time when the empirical has for the most part replaced the spiritual, what’s the value of poetry? What does it bring to the table?

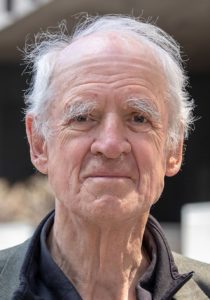

One of the intellectual giants of our generation, Charles Taylor, in a recent book, “Cosmic Connections, Poetry in the Age of Disenchantment” (Belknap Press, $29.95), answers that question. Poetry is meant to reenchant us, to help us see beyond the tedium of everyday ordinariness, to see again the deep innate connections among all things.

For Taylor, as children, we are in touch naturally with the deep innate connections among all things; however, our normal growth and development work at dissolving our original inarticulate sense of cosmic order. But we sense this loss and have an inchoate longing to recover that sense of wholeness.

And that’s where good poetry can help us.

When we experience something, we don’t simply receive it, like a camera taking a photo, we help define its meaning. In Taylor’s words, “We do not just register things; we re-create the meaning of things.” Thus, like any good work of art, the function of poetry is to transfigure a scene so that the deeper order of things becomes visible and shines through. The French poet, Stephane Mallarme, suggests that the function of art is not to paint something, but to paint the effect it is meant to produce.

For Taylor, a good poem can do that. How? By helping us see things from a bigger perspective.

Wrapped up in our own lives, we are too close and so absorbed that we cannot properly name what we are going through. “Poetry gives it a plot, a story, and this in a way that gives it a dramatic shape. We can now see our life as a story, a drama, a struggle, with the dignity and deeper meaning that it has. For example, by giving poetic expression to a distressful emotion, poetry allows us to hold it at a distance. The business of the poet is to make poetry out of the raw material of the unpoetical. As William Wordsworth once said, poetry is “emotion recollected in tranquility.”

And to do that, the poet needs to employ a different language.

Here’s how Taylor puts this: “Poetry is the ‘translation’ of insight into subtler languages. What cannot adequately be understood in instrumental language, namely, value, morality, ethics, love, and art, requires explorations that can only be carried out in other vocabularies. The language of empiricism is essentially an instrument by which we can build a responsible and reliable picture of the world as it lies before us, but that world is no longer seen as the site of spirit and magic forces. Rather the universe is now understood in terms of laws defined purely by efficient causality.”

And he goes on: “So a crucial distinction comes to the fore, between ordinary, flat, instrumental language which designates different objects, and combines these designates into accurate portraits of things and events, all of which serve the purpose of controlling and manipulating things. … [while] on the other hand, truly insightful speech [good art] reveals the very nature of things and restores contact with them. Poetic language gives us a sense that we are called, we receive a call. There is someone or something out there.”

Poetry parallels music as a paralinguistic practice. But what has any of this to do with spirituality, not least Christian spirituality? Aren’t poetry and art purely subjective and, as such, often amoral? Taylor would sharply disagree insofar as this pertains to good poetry and good art. Good art, he suggests, is never a matter “of shifting taste.”

Taylor suggests that the meanings we experience in good poetry and art have their place alongside moral and ethical demands. Why? Because, for Taylor, in good poetry and good art, “the experience is one of joy and not just one of pleasure.” The difference? “You experience joy when you learn or are reminded of something positive, which has a strong ethical or spiritual significance, whereas intense pleasure tends to enfold you even more in yourself.” For Taylor, joy awakens a “felt intuition” which is not merely subjective. It is an opening to the ontological, to God.

Finally, quoting Baudelaire, Taylor leaves us with this insight: “It is both by poetry and through poetry, by and through music, that the soul glimpses the splendor beyond the grave; and when an exquisite poem brings tears to the edge of the eyes, these tears are not the proof of an excess of enjoyment, they are rather the testimony of an irritated melancholy, of a postulation of the nerves of a nature exiled in the imperfect and which would like to seize immediately, on this earth, a revealed paradise.”

So, what has poetry to do with spirituality?

To recast St. Augustine: You have made us for yourself, Lord, and when poetry and music stir our hearts with irritated melancholy, we recognize that ultimately our rest lies in you alone.