For the uninitiated, Turner Classic Movies (TCM) has been a staple of cable and streaming services for almost as long as there have been cable and streaming services. It highlights films from the past 100 years of filmmaking.

Though most of the films resonate from the “golden era,” when monolithic movie studios dominated the landscape and churned out enormous amounts of product between the 1930s through the 1950s, TCM also shows a smattering of silent films, foreign classics, and every now and then, a film sneaks in from the 1970s or 1980s.

Each month on TCM is dedicated to a specific star or film genre. For October, TCM has decided to highlight a different kind of star, or in this case, stars: robots. Since October is the month of Halloween, it kind of makes sense.

I think watching these films from so many different eras tells us a lot more about human beings than it does robots. In many of the films, that is the intent. In others, it may be unintentional but all the more telling.

In the 1930s, awful looking robots made up of washing machine parts populated Saturday matinee serials. In the 1940s, World War II had given the world plenty of real-life monstrosities to contend with and robots went into a latent dormancy.

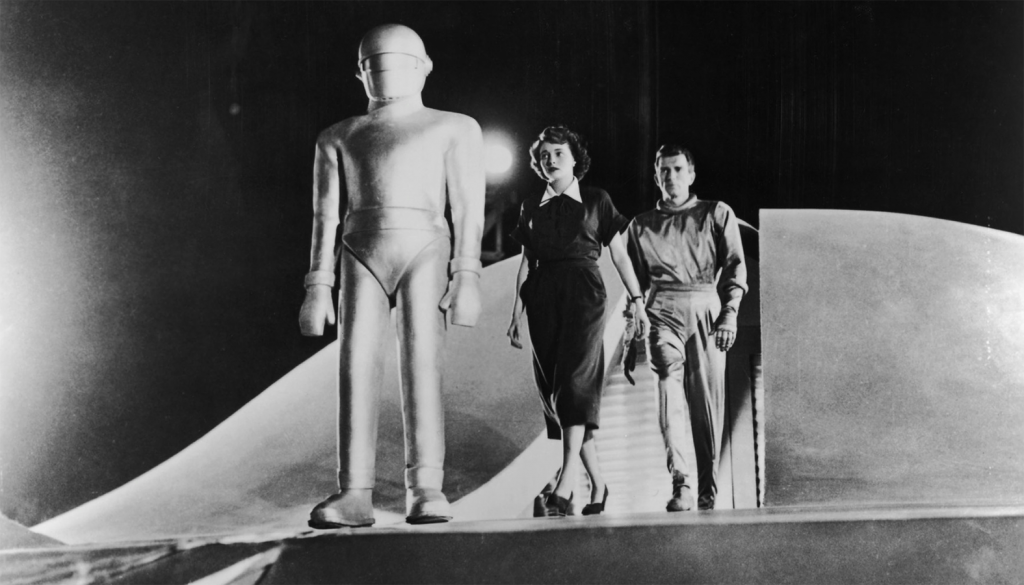

In the 1950s, robots roared back. Science fiction films of dubious budgets exploded onto drive-in movie screens like so many mushroom clouds over the Nevada nuclear testing site. With some exceptions, like TCM’s showing of “The Day the Earth Stood Still,” the robots were there to menace humanity, and to be overcome by human spirit and human ingenuity.

In “The Day the Earth Stood Still,” a menacing looking robot is actually a kind of galactic peacekeeper. This is the first taste of robot as overlord. It is a film far ahead of its time and ushers in a humanistic-centered, not God-centered, take on humanity. If the higher power is a man in a silver suit and not a first-century carpenter, then the logical progression is that the machines designed by such “higher beings” would also levitate over mere earthlings.

In the classic silent film “Metropolis,” a dystopian future (Are there ever any other kind depicted in movies?) is a bifurcated world of the select haves who live above ground, and the multitudinous workers who slave away in a subterranean nightmarish existence, making the life of leisure possible above.

A robot is created by a mad scientist with the aim that “she” will thwart a growing revolutionary movement down below. Technically speaking, this robot from a film made a century ago is still a wonder to see. But as marvelous the filmmaking accomplishment, Director Fritz Lang’s point about the dehumanizing effects of the industrial revolution is overt. Even though the robot takes on humanlike beauty, “she” is no replacement for the look-a-like heroine of the film.

Things have gotten decidedly more out of focus in the decades that followed. Though there is much to like about the Marvel Avenger movies, and I possess the capacity to suspend my disbelief these films require, I was always troubled by the arc begun in the “Avengers: Age of Ultron” movie. An artificial intelligence is implanted into a human-looking android called Vision. This is not your robot made from the imagination of a prop man and the parts department at Universal Studios in the 1950s. Vision looks human and is hyper intelligent.

The problem I have is when one of the Avengers falls in love with him.

Giving robots or monsters human feelings is not new. It ruined King Kong’s tour of the Empire State Building. What is different here and in other “robot movies” is that, unlike those from an earlier era where the robot was a device to explore fears and cultural angst about the future, now, they represent a lot of confusion we as a culture have about the essence of being human — namely, that we are made not in the image of circuitry and inorganic technology, but in the image of God.

The computer HAL in “2001: A Space Odyssey” has no outwardly robotic features, but it is a machine with a distinct personality. When his artificial intelligence becomes a lethal problem, a movie that, up until this point, was a ponderous artsy display of set pieces turns into a riveting man vs. machine struggle for survival.

Once this episode in the film concludes, the movie returns to its indecipherable, at least by me, visually stunning Stanley Kubrick home movie. Ironically, a nonbeliever like Kubrick produced one of the last films where humanity, even if it is mysterious to us, surpasses the circuitry.

Machines would pose problems for people in later films like the “Terminator” franchise, but more and more robots have become the protagonists in films and “live” not to serve humanity but to find meaning in their lives. I thought that was our job — the robot builders.

It is not much of a stretch to connect the confusion of robots as autonomous “beings” with equal claims to “life” as any mere human, with the current state of a culture where animals have been given their day in court regarding their autonomy and rights.

Worshiping the created more than the Creator is just another way of describing artificial intelligence.