Around this time of year, we Catholics begin to hear the term “Paschal Mystery” — meaning the mystery of Jesus’ death and resurrection — a lot more. But what does it really mean for you and me?

It means Jesus’ death, remembered on Good Friday, and his new life, celebrated and experienced at Easter, are ours, too.

For St. Paul, this experience happens through baptism: “We were indeed buried with him through baptism into death, so that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might live in newness of life” (Romans 6:4). In another place, he asserts, “For you have died, and your life is hidden with Christ in God” (Colossians 3:3).

Still, the terms may come off as a bit metaphorical.

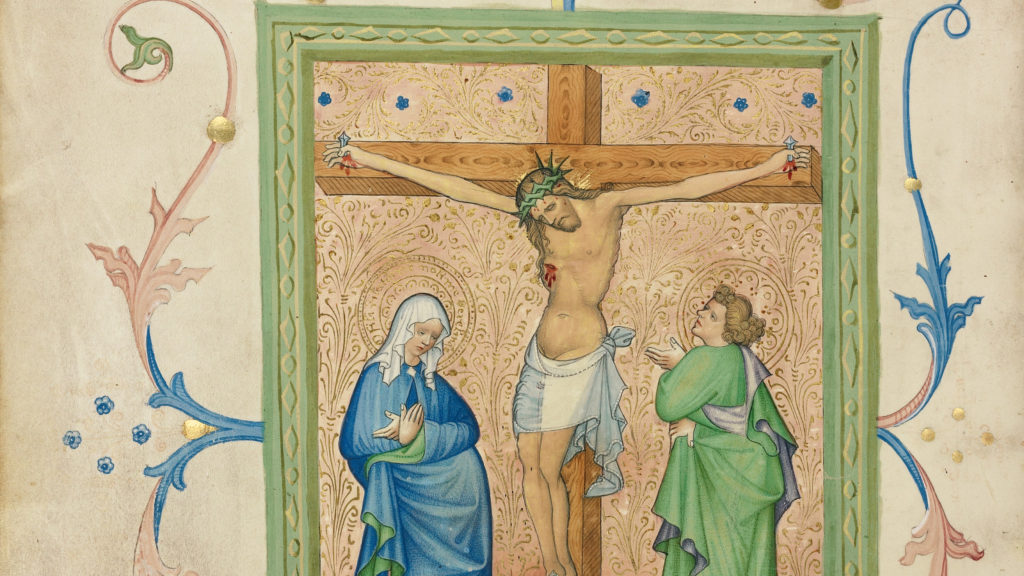

But on Good Friday, when we read the Lord’s passion according to the Gospel of John, we hear that right before his death, in the final act of his agony on the cross, Jesus entrusts us to his own mother — and her to us.

He turns to Mary and says, “Woman, behold, your son.” Then he says to John (and through him to each of us), “Behold, your mother” (John 19:26–27).

If we look at the entirety of Jesus’ life and ministry as recorded in the Gospels, we see how Jesus spent it preparing his disciples to experience the Paschal Mystery — and drawing his own mother into it, too.

Jesus’ passion and resurrection only appear at the end of his earthly journey, but they are not some unfortunate addition or epilogue to it. Rather, everything was oriented toward it from the start.

In the first chapter of the Gospel of Mark, Jesus, who has no sin, lowers himself to receive “a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins” (Mark 1:4). In solidarity with sinners, Jesus goes down into the waters of the Jordan, foreshadowing his descent into death.

In Chapter 2, he speaks of himself as the bridegroom who will be taken away, a veiled allusion to his violent death (Mark 2:20). In Chapter 3, his enemies are plotting “against him to put him to death” (Mark 3:6). As the story advances, allusions to his suffering become more frequent and more direct. Halfway through the Gospel, Jesus openly predicts his passion and resurrection as he heads to Jerusalem with his disciples.

Throughout, Jesus makes a point of calling the disciples and pulling them into his own life. Not because he wants them to suffer, but because he’s preparing them for the most important experience of their lives.

Each time he speaks of his passion, the disciples resist it, whether it’s Peter rebuking Jesus (Mark 8:32), the disciples quarreling about who is the greatest (Mark 9:34, or James and John seeking the places of honor (Mark 10:37).

Undeterred, Jesus patiently explains what kind of life he’s drawing them to: one of denying themselves and following him, giving priority to the small and vulnerable among us (Mark 9:36), taking the last place (Mark 9:35; 10:43), and receiving the kingdom like a child (Mark 10:15). Becoming servants, small and vulnerable, taking the last place, Jesus invites them into his own lifestyle, which he will exemplify most fully on the cross.

Mary is no stranger to this path of smallness, vulnerability, service, and self-denial. In the annunciation scene, she responds to God by saying “be it done unto me according to your word.” She understands that accepting God’s plan means renouncing whatever other plans she might have had.

For Mary, this means even giving up the human ties with her only son. When Jesus seemingly distances himself from her during his public ministry — “Who are my mother and [my] brothers?” (Mark 3:33) — she learns to die to the human bonds that bind her to Jesus and to give rise to a new way of relating to him. “My mother and my brothers,” Jesus says, “are those who hear the word of God and act on it” (Luke 8:21).

When her 12-year-old Son, for whom she and Joseph had anxiously looked for three days, stated that he had to be in his Father’s house, Mary and Joseph did not understand what he said to them (Luke 2:50). She struggles with understanding God’s designs and learns to accept what surpasses understanding, a lesson she will undertake again at the cross.

In a small but telling detail, St. Luke tells us that she mentions Joseph first: “Your father and I have been looking for you” (Luke 2:48). Mentioning Joseph first, she takes the last place.

Because she is so perfectly set on the path of smallness, self-denial, service, and childlike trust, Jesus wants us to hold on to her — “Behold, your mother” — as we enter our dying and rising with Christ. She will intercede for us when our wine runs short. And she will encourage us — “Do whatever he tells you” (John 2:5) — to help bring about the new wine so that “we too might live in newness of life.” (Romans 6:4)

This is good news. This Easter, if we’re struggling to be small, take the last place, or trust in God; her Son wants us to enter the Paschal Mystery with his mother, holding on to her as we live out our dying and rising with Christ.