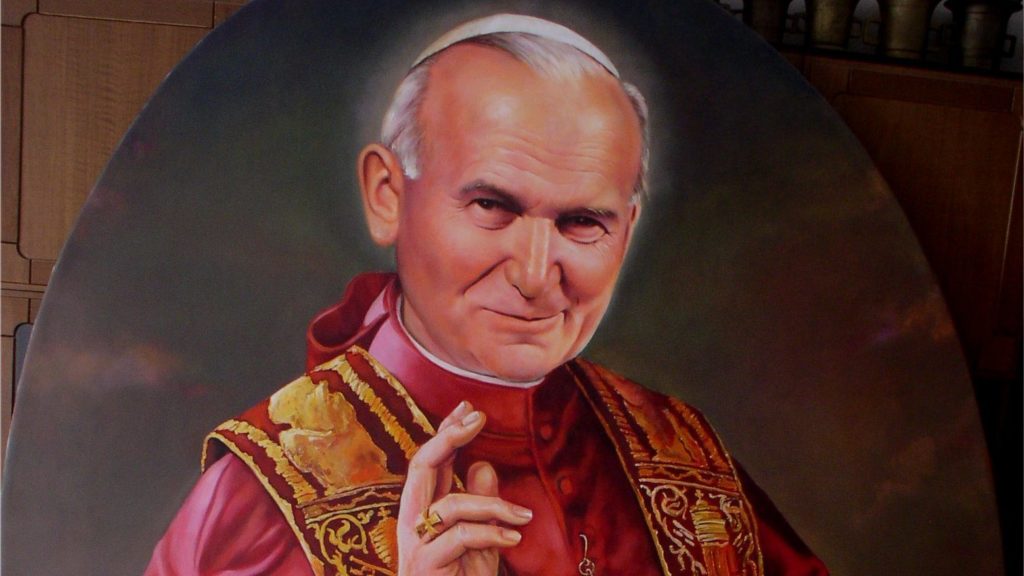

It still makes me smile when I see the feast day coming up on the calendar: Oct. 22, St. John Paul II, pope.

I met him, briefly, not long after I became Catholic. I spoke with him about a theologian we both admired: Matthias Scheeben. He consoled me on the death of my father.

And all the while this new Catholic was thinking: Am I really speaking with the pope?

Today, as an old Catholic I look at the calendar and think: Did I really speak with a saint?

John Paul embodied God’s fatherhood to a household as big as the world. Because he was a father, he witnessed to the unity of all God’s family. And he spoke to that family in a language with universal appeal — the language of the Bible. As a Protestant, I was first drawn to him by the beautiful and brilliant way he wove Scripture into everything he did.

That particular quality set him apart from his predecessors of the post-Reformation era. It’s not that these men were unscriptural or anti-scriptural. But they represented a profoundly different pastoral style. Their methods were scholastic, precise, emphasizing ever-finer distinctions in thought. Moreover, their pastoral style set the tone for preachers and teachers throughout the Catholic world. So Protestants, of my cast of mind at least, found Catholic literature easy to dismiss as insufficiently biblical.

But John Paul took up the model of the Second Vatican Council, which itself had been profoundly shaped by the mid-20th-century “return to the sources” — the Catholic biblical, liturgical, and patristic movements.

John Paul began his term with the biblical “Be not afraid,” the exhortation of prophets and angels — and God himself — uttered whenever history, whether personal or civilizational, had taken a momentous turn (see, for example, Genesis 46:3 and Luke 2:10). And he confirmed his pervasively scriptural style in all of his early documents. In his first encyclical, Redemptor Hominis (“The Redeemer of Man”) in 1979, 10 out of the first 12 footnotes direct the reader to the Bible; and almost three-quarters of the 205 notes throughout the document are scriptural citations.

Even his “theology of the body” addresses, delivered 1979-81 and continued in 1984, were not merely theological arguments or pastoral exhortations.

They were sustained and technical studies of texts from the Book of Genesis, the Gospel of Matthew, and St. Paul’s Letter to the Ephesians, selectively drawing from modern Scripture scholarship.

As pope, he synthesized and proclaimed the teachings of Vatican II in the language of Vatican II, which is the language of the Bible.

How fitting that he died exactly 40 years after the close of Vatican II. In biblical terms, 40 years is a generation. His papacy embodied Vatican II. He presented the fullness of faith to the world in the most understandable ways, and drew millions, including me, into the heart of the Church. The end of his papacy was the end of a generation.