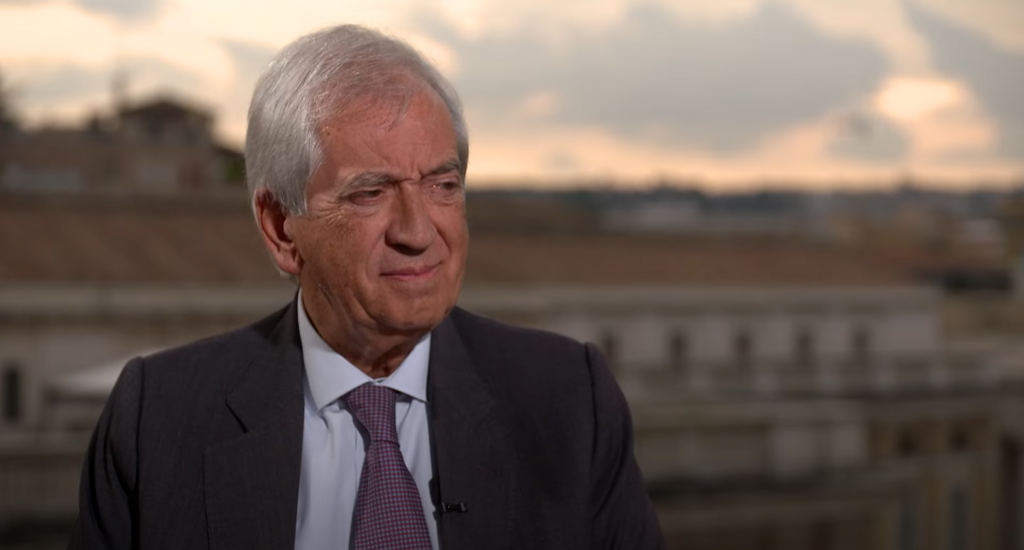

ROME — To be honest, it’s sometimes difficult to know quite what to make of Libero Milone, the former auditor general of the Vatican, who was ousted in 2017 and who’s tried ever since to present himself as a martyr for the cause of reform.

Most recently, Milone staged a press conference in Rome a day after Vatican officials showed a distinct lack of enthusiasm for a $9.6 million lawsuit against the Secretariat of State that Milone and a former deputy hope to file in the Vatican’s civil tribunal, refusing to authorize Milone’s chosen lawyer to appear before Vatican courts. The two men are seeking compensation for damage to their reputations and livelihoods, and, in the case of the deputy, also harm to his health.

During the news conference, Milone angrily called the Vatican’s legal system “Orwellian” and the silence of Pope Francis on his case “deafening.”

A former CEO of Deloitte in Italy, Milone was hired by Pope Francis in 2015 to become the first auditor general of the Vatican, one of three new institutions created by the pontiff a year earlier to undergird his financial reform. Milone was supposed to serve a five-year term, but instead was canned two years later under circumstances which, to this day, remain murky.

Repeatedly, Milone has suggested he was removed because he knew too much, and that he and his team were on the verge of exposing the misdeeds of powerful figures such as Italian Cardinal Angelo Becciu — who, at the time, was the No. 2 official in the Secretariat of State, and who’s now on trial before the Vatican court for financial crimes.

Milone also charged that he and his team were being spied on by Cardinal Becciu and former Vatican security czar Domenico Giani, despite the fact that one of the charges against Milone was that he was spying on other senior Vatican officials.

Milone has claimed that certain documents related to his case have been forged, either in part or in whole, and that prior to his dismissal he was subjected to an abusive interrogation by Gianni and compelled to sign what amounted to a prefabricated “confession.”

Making the whole thing even more macabre, Milone’s deputy, Ferruccio Panicco, is a cancer patient who claims Vatican investigators seized his medical records and refused to return them, forcing him to restart treatments and impairing his chances of surviving prostate cancer.

It’s all so tangled that it’s tempting to write off the Milone saga as a soap opera, the rights and wrongs of which are basically impossible to adjudicate.

The problem with that instinct is that it ignores one salient fact: Milone is hardly an isolated case.

By now, you actually could field an entire football team with all the personalities brought into the Vatican to promote financial reform but who, in one way or another, ended up as casualties of the process.

Beyond Milone and Panicco, the lineup includes:

- René Brülhart, former president of the Vatican’s Financial Information Authority

- Tomasso di Ruzza, Brülhart’s top deputy

- Ettore Gotti Tedeschi, former president of the Institute for the Works of Religion (the “Vatican bank”)

- Ernst von Freyberg, also a former president of the Institute for the Works of Religion

- Cardinal George Pell, former secretary for the Economy under Pope Francis

- Danny Casey, an Australian businessman and Pell’s top aide

- Joseph Zahra, a founding member of the Vatican’s Council for the Economy

- George Yeo, also a founding member of the Vatican’s Council for the Economy

- Giulio Mattietti, a former vice-director of the Institute for the Works of Religion

In some cases, these individuals were either forced out or actually charged with some form of misconduct. In others, they were simply quietly let go, replaced by other personalities who signified a change in direction.

Included in that group is a former member of the board of directors of Parmalat and the Italian chairman of Santander Consumer Bank; a former vice-chair of the Egmont Group, the world’s leading consortium in the fight against money laundering the financing of terrorism; a financial analyst for Three Cities Research; a former CFO for a sprawling archdiocese; a professionally licensed data protection officer; a former head of the largest bank in Malta; and, last but not least, a former foreign minister in Singapore.

At one point or another, all these figures were hailed by Vatican spokespersons as symbols of a bright new day of financial transparency and accountability dawning under Pope Francis. Eventually, however, all were either cut loose — in some cases, actually charged with crimes before a Vatican tribunal — or simply allowed to fade away.

Is it possible that all 11 of these individuals, despite their reputations for professional success and integrity in other arenas, turned out to be incompetent, corrupt, or simply unhelpful, at least as far as their Vatican service goes?

In theory, sure, though the odds against such a scenario would seem fairly long.

Another explanation, arguably more probable, would be that there’s an establishment inside the Vatican which resents outsiders and resists change. Despite all of Pope Francis’ attempts at reform, that establishment still wields time-honored methods for showing outsiders the door — gently and quietly when possible, harshly and loudly if necessary.

It may well be, as his detractors suggest, that Milone has a bit of a persecution complex. Given that he’s hardly alone, however, it’s probably worth considering the possibility that the problem may not be entirely in his imagination.