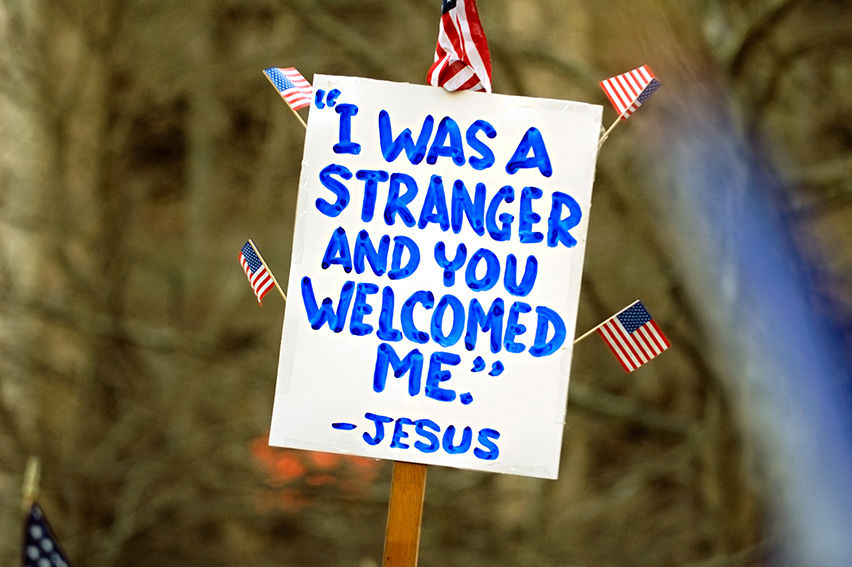

Whenever we have been at our best as Christians, we have opened our churches as sanctuaries to the poor and the endangered. We have a long, proud history wherein refugees, homeless persons, immigrants facing deportation and others who are endangered take shelter inside our churches. If we believe what Jesus tells us about the Last Judgment in the twenty-fifth chapter of Matthew’s Gospel, this should serve us well when we stand before God at the end.

Unfortunately, our churches have not always provided that same kind of sanctuary (safety and shelter) to those who are refugees, immigrants and homeless in their relationship to God and our churches. There are millions of persons, today perhaps the majority within our nations, who are looking for a safe harbor in terms of sorting out their faith and their relationship to the Church.

Sadly, too often our rigid paradigms of orthodoxy, ecclesiology, ecumenism, liturgy, sacramental practice and canon law, however well-intentioned, have made our churches places where no such sanctuary is offered and where the wide embrace practiced by Jesus is not mirrored. Instead, our churches are often harbors only for persons who are already safe, already comforted, already church-observing, already solid ecclesial citizens.

That was hardly the situation within Jesus’ own ministry. He was a safe sanctuary for everyone, religious and nonreligious alike. While he didn’t ignore the committed religious persons around him, the Scribes and Pharisees, his ministry always reached out and included those whose religious practice was weak or nonexistent. Moreover, he reached out especially to those whose moral lives were not in formal harmony with the religious practices of the time, those deemed as sinners.

Significantly, too, he did not ask for repentance from those deemed as sinners before he sat down at table with them. He set out no moral or ecclesial conditions as a prerequisite to meet or dine with him. Many repented after meeting and dining with him, but that repentance was never a precondition. In his person and in his ministry, Jesus did not discriminate. He offered a safe sanctuary for everyone.

We need today in our churches to challenge ourselves on this. From pastors to parish councils — and from pastoral teams to diocesan regulators to bishops’ conferences, to those responsible for applying canon and church law, to our own personal attitudes — we all need to ask: Are our churches places of sanctuary for those who are refugees, homeless and poor ecclesially? Do our pastoral practices mirror Jesus? Is our embrace as wide as that of Jesus?

These are not fanciful ideals. This is the Gospel, which we can easily lose sight of, for seemingly all the right reasons. I remember a diocesan synod where I participated some 20 years ago. At one stage in the process we were divided into small groups and each group was given the question: What, before all else, should the Church be saying to the world today?

The groups returned with their answers and everyone, every single group, proposed as its first-priority apposite what the Church should be saying to the world as some moral or ecclesial challenge: We need to challenge the world in terms of justice! We need to challenge people to pray more! We need to speak again of sin! We need to challenge people about the importance of going to church! We need to stop the evil of abortion! All of these suggestions are good and important. But none of the groups dared say: We need to comfort the world!

Handel’s “Messiah” begins with that wonderful line from Isaiah 40: “Comfort, comfort my people, says your God.” That, I believe, is the first task of religion. Challenge follows after that, but may not precede it. A mother first comforts her child by assuring it of her love and stilling its chaos. Only after that, in the safe shelter produced by that comfort, can she begin to offer it some hard challenges to grow beyond its own instinctual struggles.

People are swayed a lot by the perception they have of things. Within our churches today we can protest that we are being perceived unfairly by our culture, that is, as narrow, judgmental, hypocritical and hateful. No doubt this is unfair, but we must have the courage to ask ourselves why this perception abounds, in the academy, in the media and in the popular culture. Why aren’t we being perceived more as “a field hospital” for the wounded, as is the ideal of Pope Francis?

Why are we not flinging our church doors open much more widely? What lies at the root of our reticence? Fear of being too generous with God’s grace? Fear of contamination? Of scandal?

One wonders whether more people, especially the young and the estranged, would grace our churches today if we were perceived in the popular mind precisely as being sanctuaries for searchers, for the confused, the wounded, the broken and the nonreligious, rather than as places only for those who are already religiously solid and whose religious search is already completed.

Oblate of Mary Immaculate Father Ronald Rolheiser is a specialist in the field of spirituality and systematic theology. His website is www.ronrolheiser.com.