Many people wake up on New Year’s morning with firm resolutions in mind — and many of those resolutions are related to alcohol.

Some want to give up drinking. Some want to cut back. Some turn to Alcoholics Anonymous or other groups for support. Still others take the decisive step of entering rehab.

All can look to Father Theobald Mathew as a patron. He played a gigantic role in founding the movement, now diverse and widespread, to help problem drinkers help themselves.

A Capuchin Franciscan, Father Mathew served in Ireland after the Acts of Union that merged his country with Great Britain as a single “United Kingdom.” Native Irish, and especially Irish Catholics, awoke in the early 1800s to find themselves second-class citizens in their own land.

The country sank into an economic and moral depression, and people took refuge in drink.

In the 1830s, per capita annual consumption of beer and whiskey hovered around 3.5 gallons of each.

Habitual drunkenness kept the Irish people impoverished and resentfully dependent on their British overlords. Yet they were unable to sustain any movements of social change. Resistance meetings regularly degenerated into drunken brawls. A third of Ireland’s people in the 1830s were paupers.

Everyone knew there was a problem, but everyone seemed helpless to do anything about it.

Various temperance movements arose and failed. Often their founders were evangelical Protestants, and so were viewed with suspicion by the fiercely Catholic Irish people. Protestant temperance advocates knew they could make no progress until they found an ally in the Catholic clergy.

In the mid-1830s, a Quaker temperance leader approached Father Theobald Mathew. Father Mathew was renowned as a pastor and confessor and for his work with the poor, but he had no connection with the total-abstinence movement. In fact, two of his brothers and one of his brothers-in-law owned distilleries. Father Mathew himself enjoyed wine, brandy and spirits, though never to excess.

But he had to admit that many of the paupers he met were poor precisely because of alcohol abuse. On reflection, Father Mathew felt conscience-bound to take up the cause of teetotalism. “Here goes, in the name of God,” he declared, and he pledged never to drink alcohol again.

And then he called others, too, to do as he had done.

Ireland was ready for Father Mathew. His success was swift and stunning. Within a year, the local society alone had increased fourfold to 24,000 members.

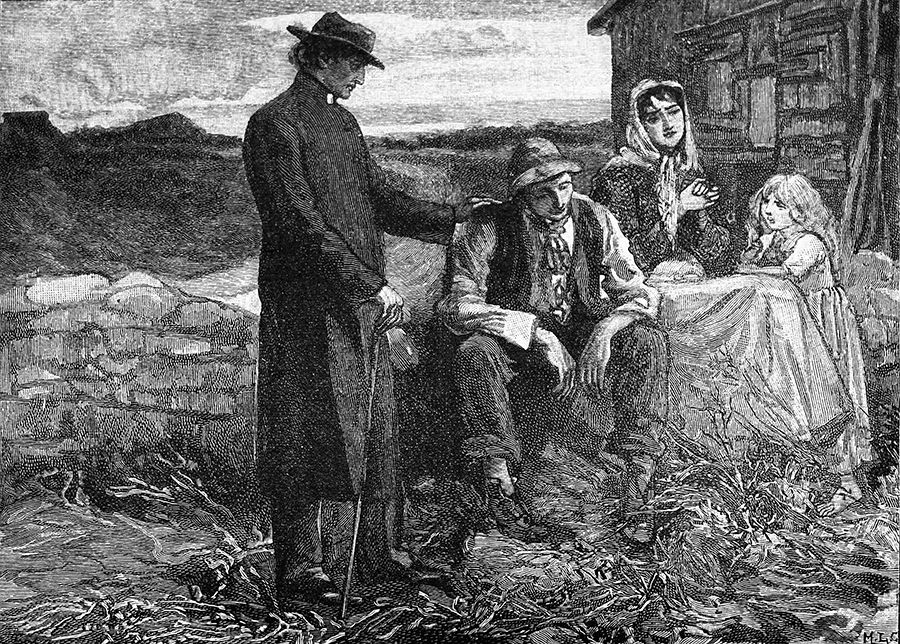

From his home in Cork, Father Mathew traveled all over Ireland and drew crowds in the hundreds of thousands. At each appearance, he stood for hours while the men, women and children came before him — one at a time — and knelt and recited the words of the total-abstinence pledge: “I promise, while I belong to the Teetotal Abstinence Society, to abstain from all kinds of intoxicating drinks, unless used medicinally, and that I will discountenance, by advice and example, the cause of intemperance in others.”

A little over two years after he joined the movement, he had personally brought 2.5 million into it — 30 percent of the total population of Ireland. By 1845 that number had more than doubled, to 6 million, and teetotalers held a clear majority.

The effect on Irish society was astonishing. Consumption of spirits dropped by half. Felony convictions decreased by a third.

Father Mathew’s success was incontestable, but it was also controversial. Some Irish clergy even accused him of heresy. They pointed out that Jesus himself took wine, used wine in the institution of the Eucharist and turned water into wine for a wedding feast. Therefore, alcohol consumption was not intrinsically evil, and could in fact be considered a great good.

These critics thought it wiser to counsel moderation, though they acknowledged that there were some for whom moderation did not work. The moderationists wrote off such “drunks” as incorrigible.

Father Mathew responded by making a distinction. The cardinal virtue of temperance does, he pointed out, enjoin everyone to moderation in drinking. Moderation fulfills the requirement, but total abstinence is the perfection of the virtue.

He drew an analogy. Everyone is called to chastity in sexual matters, but some are called to its perfection, which is celibacy; so, in a similar way, all are called to temperance in the consumption of alcohol, but some are called to its perfection, which is total abstinence.

His opponents weren’t exactly won over, but Father Mathew kept working.

In 1845, the great Irish Potato Famine placed greater demands on him. He opened a soup kitchen that fed up to 4,000 people each day. And every day, he gave 60 to 70 paupers a decent burial in his cemetery.

And he didn’t let up in his barnstorming against drink. He worked himself to exhaustion. In April 1848, when he was 57 years old, he suffered a stroke that left him partially paralyzed, but he recovered sufficiently to continue his plans for a voyage to America the following year.

In the United States he was greeted as an A-List celebrity. In New York City he stayed as a guest at the home of the mayor. He dined at the White House, where President Zachary Taylor raised a toast in his honor. (It was a glass of water, of course.) In the Senate, Father Mathew was admitted to the floor, only the second foreign visitor to be so honored. At the end of his two-year tour, he had pledged more than a half million people in U.S. cities.

It was to be his last glorious act. Soon after arriving home he retired, exhausted, from temperance work. Early in 1856 he suffered another stroke, and he died on Dic. 8 of that year.

But his work continued, and his movement gained much momentum in the following century.

Those who woke up pledging sobriety on Jan. 1 this year can thank Father Mathew for first spreading the idea abroad.

What can you do?

‚Ä¢ Pray the “Serenity Prayer,” composed by the Protestant theologian Reinhold Niebuhr (1892-1971): “God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change; courage to change the things I can; and wisdom to know the difference.”

‚Ä¢ Read books written by others who’ve chosen sobriety — like Heather King’s “Parched” and “Redeemed,” or “The Soul of Sponsorship: The Friendship of Fr. Ed Dowling, S.J. and Bill Wilson in Letters,” by Robert Fitzgerald, SJ.

• Visit helpful websites:

— Calix Society: CalixSociety.org

— National Catholic Council on Addiction: NCCAtoday.org

— Alcoholics Anonymous: AA.org

— National Council on Seniors Drug & Alcohol Rehab: https://rehabnet.com

• Talk to your parish priest.

• Attend a meeting of Alcoholics Anonymous. Visit the AA.org website to find one nearby.

Mike Aquilina is the author of more than 50 books, including “The Mass of the Early Christians,” and co-author with Cardinal Donald Wuerl of “The Mass: The Glory, the Mystery, the Tradition.” His most recent book is “A History of the Church in 100 Objects.”

Interested in more? Subscribe to Angelus News to get daily articles sent to your inbox.