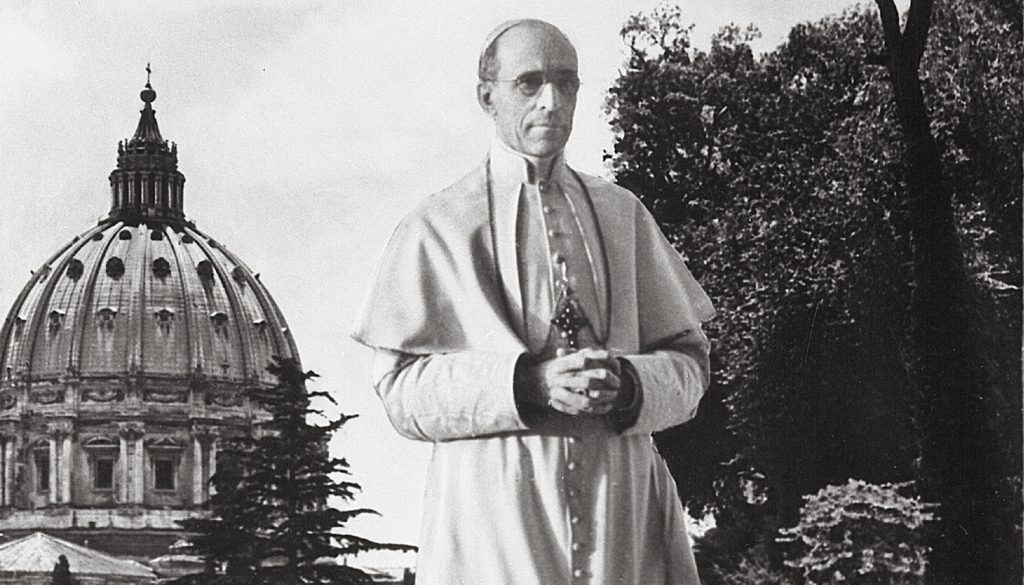

ROME — Though the Vatican’s archives on Pope Pius XII were only accessible for a few days after their historic March 2 opening, which was nine years in the making but which had to be shut down again due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, it turns out that was more than enough time to reignite what have mockingly been dubbed the “Pius Wars.”

The term refers to a historical back-and-forth that’s been bubbling since the early 1960s over whether Pope Pius, who governed the Catholic Church during World War II, was, in the infamous title of John Cornwell’s book, “Hitler’s Pope,” or whether he actually was a quiet hero who defended Jews and deserves the mantle of sainthood.

In general, the dynamics of the debate work like this.

Liberals convinced the institutional Church is fatally flawed tend to embrace the idea that Pope Pius reflected a Christian variant of antisemitism that helped pave the way for the Holocaust, because it serves a reform agenda. Conservatives who tend to reflexively defend the institution when it’s under attack spurn that claim because, well, among other things, it serves to discredit liberals.

What all this reinforces is a point that should have been clear long ago: The idea that the definitive opening of the Pope Pius archives would settle the historical debate over the wartime pontiff was always delusional. In all likelihood, any future detail to emerge from one of the roughly 200,000 moldy boxes containing some 2 million documents from 1939 to 1953 will simply provide additional grist for the mill.

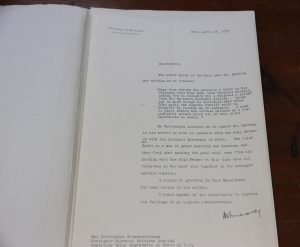

The latest case in point came in early March, when a German Church historian named Father Hubert Wolf, who leads a team of researchers from the University of Munster, announced that they’d discovered a previously unknown letter that appears to suggest the Vatican was aware of mass killings of Jews in Nazi-occupied Warsaw and Lviv in September 1942 because it was presented with an inquiry from the U.S. government citing a Jewish Agency for Palestine report.

According to Wolf, the Vatican under Pope Pius failed to take those reports seriously, citing a memo by a low-level official in the Secretariat of State, Msgr. Angelo Dell’Acqua, informing the U.S. that Rome couldn’t confirm the report and advising caution because Jews “easily exaggerate.”

(In reality, according to historian Michael Hesemann, what Msgr. Dell’Acqua actually wrote was that exaggerations in wartime are common, “also among Jews.”)

“This is a key document that has been kept hidden from us because it is clearly anti-Semitic and shows why Pius XII did not cry out against the Holocaust,” Father Wolf has been quoted as saying.

Predictably, a number of defenders of Pope Pius have swung into action, arguing the document is not the bombshell Father Wolf implies, and citing anew the wartime pope’s numerous behind-the-scenes gestures of solidarity and support for Jews.

Unsurprisingly, it turns out that Father Wolf is identified with the liberal side of most German Catholic debates. The headline of a profile last year by the Katholische Nachrichten-Agentur, the main German Catholic news agency, described him as a “thorn in the side to conservatives,” noting that Father Wolf has advocated the abolition of clerical celibacy, a more “contemporary” sexual morality and the popular election of bishops.

Meanwhile, some of the most withering commentary about Father Wolf’s purported revelation has come from robustly conservative commentators and sites, all of which confirms that the crossfire is about ideology at least as much as evidence.

Complicating things further is the fact the debate over Pope Pius inevitably influences the relationship between Catholics and Jews, since many Jewish historians and activists share a critical view of Pope Pius’ record.

To the extent that facts still matter in such a context — and it would be naïve to believe they’ll be the only thing, or even the primary factor — here they are.

The big picture about Pope Pius vis-à-vis the Holocaust is clear. He knew about mass killings of Jews, even if the full scale wasn’t clear, and to the extent he judged prudent, he denounced it, for instance in his famous Christmas address of 1942, in which he referred to the “hundreds of thousands of persons who, without any fault of their own, sometimes only for reasons of nationality or ethnicity, are destined for death or progressive elimination.”

However, Pope Pius avoided grander public gestures, such as excommunicating Catholics in the Nazi regime, because he felt doing so would make things worse, both for Jews and the institutional Church he was elected to lead.

One can think that was the right course or not, but no further historical evidence will ever change opinion because it’s counterfactual: not what the pope did, but what he should have done.

If Pope Francis or anyone else in the Church’s power structure is waiting to move forward with Pope Pius’ sainthood cause on the theory that perhaps additional evidence will end the controversy, therefore, that’s deeply unlikely.

Alas, there’s no magic bullet to avoid the hard judgment involved in looking at a complicated, mixed historical record, and discerning whether or not sanctity can still be glimpsed through it all.