Nellie Mae Rowe (1900-1982) was a self-taught artist from Fayetteville, Georgia, known for her colorful drawings, sculptures, hand-made dolls, collages, and “home installations.”

In fact, over time she made her entire home, a modest clapboard structure located on a busy street in the Georgia town of Vinings, into a giant work of art she called her “playhouse.”

Adorned with dinnerware hung from trees, festooned with colored lights, and surrounded by chewing gum sculptures, Christmas ornaments, and plastic images of Jesus, the dwelling irresistibly drew attention.

Passing cars rubbernecked, slowed down, and often screeched on the brakes and stopped.

Through Aug. 17, LA’s California African American Museum is featuring an exhibit of her work — the first in 25 years — called “Really Free: The Art of Nellie Mae Rowe.”

Rowe was the second youngest of 10 children, nine girls and a boy. Her daddy had “lived in slavery times” and taught the children to pick cotton, haul corn, and plow. Nellie Mae didn’t care for any of those activities. “I just liked to draw and make dolls.”

“When I was a little girl I would lay down on the floor and get my pencil and draw. I would draw all different things and after I finished drawing I would go in the kitchen and steal some flour, make it up into dough, and stick the drawings up on the wall. My sister would say. ‘Mama, make Nellie quit putting those drawings up,’ but Mama would let me go on doing it.”

Her mother quilted, and sewed all the girls’ dresses, and Rowe remembers making her own first doll at the age of 10.

But she was put to work in the fields early, and ran off at 17 to marry her first husband, who died six years later. She then married Henry Rowe, a farmer several years her senior. They built the house in Vinings in 1936, and Nellie Mae began working as a domestic for the family across the way, a job she would hold for the next 30 years.

Once in a while she’d draw: nothing much, a big picture on brown paper.

When Henry died in 1948, however, she started to let loose, hanging strings of beads, bottles, and stuffed animals from bushes and trees around the house.

But it was only in the late 1960s, when she was no longer working for the Smiths, that she was free to practice the art she was born for. “This is the talent that [God] gave me and I have to use it,” she proclaimed.

She’d been trained since birth in “making do”; she’d always been able to make something out of nothing.

And in the last decade and a half of her life, Nellie Mae Rowe burst into bloom.

Drawing on pieces of cardboard, recycled paper, fabric, and even pancake mix lids, she made exuberant crayon paintings, often depicting the activities and rituals of her childhood: “Untitled (Nellie Mae Making it to Church Barefoot),” 1978-82, for example.

She drew pictures of herself surrounded by plants, flowers, and friendly beasts. Another drawing, playfully expressing her joy to be free at last from household drudgery, declares, “My house is Clean Enough To Be helty and it Dirty Enough To Be happy.”

Over time, her work became increasingly sophisticated. Whether her subject was one of the wrestlers she loved to watch on TV — in particular, Claude “Thunderbolt” Patterson, or the mystery of a woman’s capacity to give birth, she moved from concentrating on a single figure to complex compositions with flowing but controlled lines.

Rather than directly addressing the social and political concerns of the day, Rowe’s “statement” was her art, her very life.

“I am black and I love my blackness,” she told a reporter in 1978. She also once said, “I have no energy to draw pictures about slavery times. It makes me feel sad. You must not think back to those times because these are new days.”

During the late ’70s and into the ’80s, Rowe’s work gradually came to be celebrated; she is now recognized as one of America’s premier folk artists. Her work is held in numerous collections, including The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Morgan Library, the American Folk Art Museum, all in New York City; as well as museums in Atlanta, Dallas, Baltimore, and many other major cities.

An experimental documentary based on Rowe’s life and art was launched in 2023. Runs the trailer: “Chewing gum sculptures, a wealthy gallerist, a firebrand wrestler, a notorious murder case and the segregated south — it’s all part of Nellie Mae Rowe’s boundless universe. “This World is Not My Own” reimagines this self-taught artist’s world and her life spanning the 20th century.”

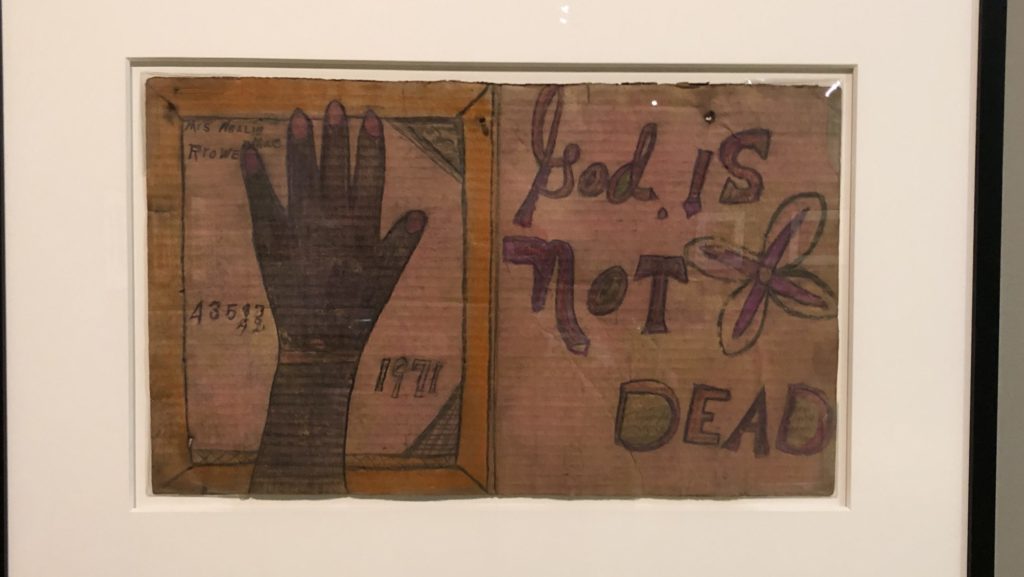

“God Is Not Dead” (1971), a simple work in crayon and pencil on corrugated cardboard, could be her credo. A framed black hand, a drawing within a drawing, is outstretched in wonder, triumph, and praise.

“The pictures I am proud of that I have made are of my hand. I leave my hand on the wall. When I’m gone they can see a print of my hand. I love that — to see a print of my hand. I’ll be gone to rest but they can look back and say ‘that is Nellie Mae’s hand.’ ”