The benchmark for great literature is its timelessness. Frankly, I wish Charles Dickens’ “A Tale of Two Cities” wasn’t so relevant right now. But in light of recent events, a quick review of this book feels like it was written yesterday, which makes it a handy manual for navigating the turbulent waters of our latest, non-microbe crisis. Besides the ability to continue to provoke and inspire, great literature, like Dickens’ novel, juggles more than one thought at a time effortlessly.

One of the primary thoughts in “A Tale of Two Cities” that makes it so “current” details the social injustices of 18th-centiry aristocratic France that necessitated a response, but had that response devolve into the insanity of groupthink and mob rule.

Not wanting to spoil the ending for anyone considering reading the book or to give some free book report fodder for any lazy eighth-grader, suffice it to say the protagonist of “A Tale of Two Cities” is a man motivated and changed forever by love.

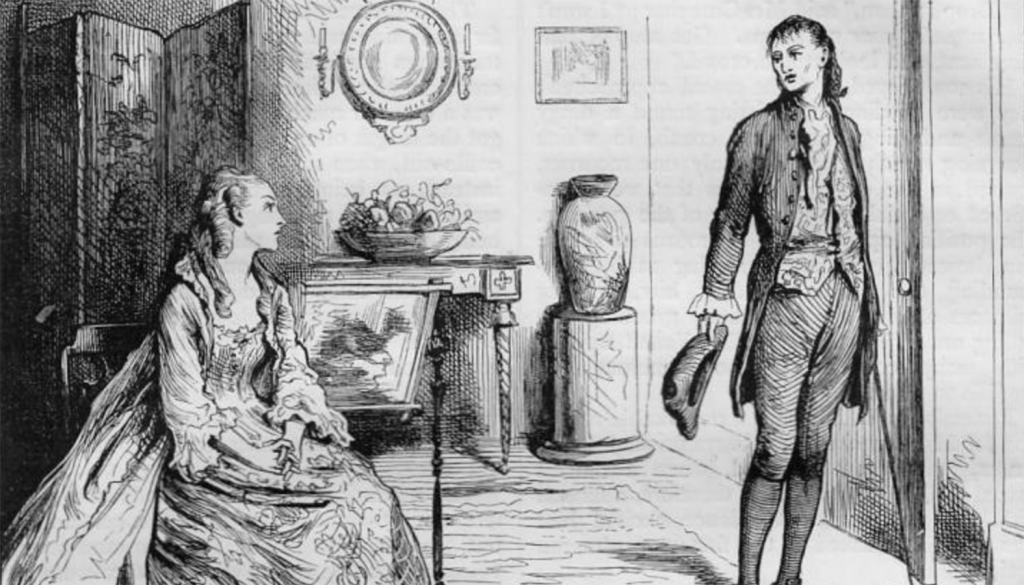

At first, the character of lawyer Sydney Carton thinks the love he has for a beautiful young woman in distress is the eros kind. He soon discovers her heart belongs to another, which begins his momentous transformation, and through a series of twists, turns, and conscious decision-making on his part to be a better man, he embraces the agape form of love, and in doing so, changes the world — the world of the woman he loves from afar. You eighth-grader, you have to read the book to find out how he does that.

The story unfolds under the cloud of the French Revolution. Since what I’ve been seeing being played out on LA’s streets reminds me of the French Revolution, I returned to Dickens’ story for reference and a little inspiration. I found both.

Dickens does not sugarcoat atrocities committed by those in power, and is likewise not timid about painting members of the ruling class with the dark and ominous colors they deserve. Yet he is also quick to show us what happens when a mob is left to its own devices and groupthink begins to creep into every crevasse left open by a declining sense of order.

The book is not a polemic against injustice and cruelty, though injustice and cruelty are exposed like gaping wounds from all sides in the universe Dickens creates. But he is after bigger game, and that is where we should all be looking right now. The author is much more concerned about the journey taken by his main character and how that journey will impact the people in his orbit. Again you eighth-grader, you’re on your own; just be assured the impact Sydney Carton makes is lasting and profound.

Dickens wrote fiction, but real life is filled with people who swam against the tide or did not go along when a mob became a singular organism, almost always leading to death and destruction. No one remembers the name of the man who wielded the axe upon St. Thomas More, but we do remember St. Thomas.

Not one person in the crowd before Pilate was identified by name, but Joseph of Arimathea returned to Pilate after the fact and did the right thing. The names of the legions of Selma police officers with their fire hoses and German shepherds are lost to history, but we remember the name Martin Luther King Jr.

As in “A Tale of Two Cities,” sometimes the real world turns on the action of an individual. It rarely turns, for the better at least, from the actions of a mob bent on vengeance or revolution.

Mobs, like the one Dickens shows, who cheer enthusiastically with every drop of a guillotine’s blade, take on a singular character and seem to swallow up individuals who may, by themselves, never consider letting out a howl of approval at a decapitation, or pick up a rock and hurl it through a storefront window. Mobs have acted this way long before Dickens was born and as we have seen lately, continue to manifest the same power over people, long after the author’s death.

Injustice will be with us always, and putting “faith” into any man-made system and expecting Utopia is a fool’s errand.

But there is an answer to our current nonfictional situation. And it’s the same answer we’ve known since Pontius Pilate had truth staring him right in the face.