The biblical story of Saul is one of the great tragedies in all of literature. Saul’s story makes Hamlet look like a Disney character. Hamlet, at least, had good reasons for the bitterness that beset him. Saul, given what he started with, should have fared better, much better.

His story begins with the announcement that, in all of Israel, none measured up to him in height, strength, goodness, or acclaim. A natural leader, a prince among peers, his extraordinary character was recognized and proclaimed by the people. They made him their king. The beginning of his story is the stuff of fairy tales, and it goes on in this way for a while.

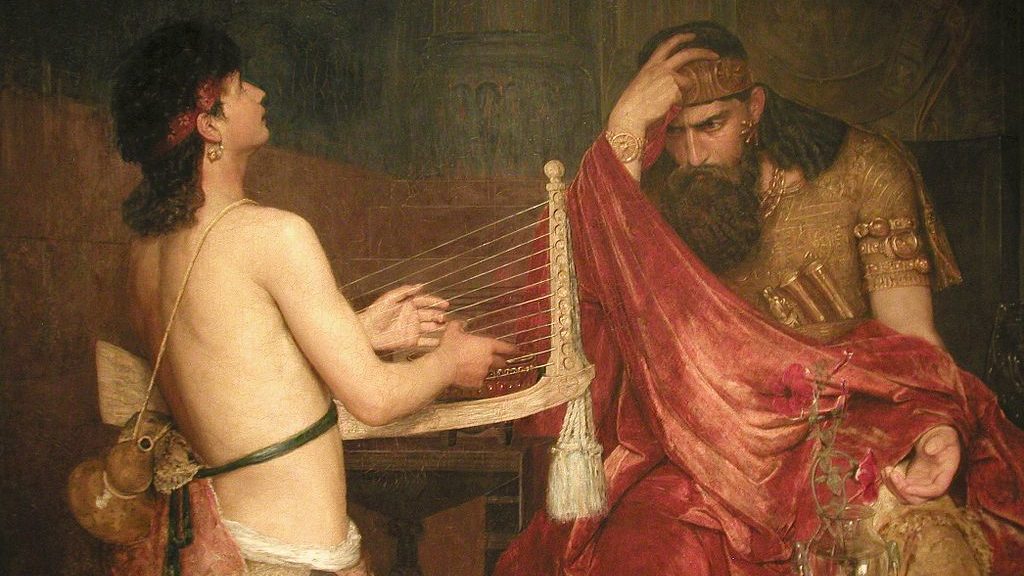

However, at a point, things begin to sour. That point was the arrival of David on the scene — a man younger, more handsome, more gifted, and more acclaimed than he was. Jealousy sets in and envy begins to poison Saul’s soul. Looking at David, he sees only a popularity that eclipses his own, not another man’s goodness, nor indeed what that goodness offers to others. Instead, he grows bitter, petty, hostile, tries to kill David, and eventually dies by his own hand, an angry man who has fallen far from the innocence and goodness of his youth.

What happened here? How does someone who has so much going for him — goodness, talent, acclaim, power, blessing — grow into a bitter, petty man who ends up taking his own life? How does it happen? The late Margaret Laurence, in a brilliant, dark novel, “The Stone Angel” (University of Chicago Press, $17), offers a good description of how this happens and how it happens in ways that are hidden to the one undergoing the transition.

Her main character, Hagar Shipley, is a “Saul” of sorts. Hagar’s story begins like his: She is young, innocent, and full of potential. What’s to become of such a beautiful, bright, talented, young woman? Sadly, not much at all. She drifts into everything: adulthood, an unhappy marriage, and into a deep unrecognized and unspoken disappointment that eventually leaves her slovenly, frigid, bitter, and without energy or ambition.

What’s as remarkable as sad is that she doesn’t see any of this herself. In her mind, she remains the young, innocent, gracious, popular, attractive young girl she once was in high school. She doesn’t notice how small her world has become, how few real friends she has, how little she admires anything or anyone, or even how physically unkempt she has become.

Her awakening is sudden and cruel. One winter day, shabbily dressed in an old parka, she rings the doorbell of a house where she is delivering some eggs. A bright young child answers the door and Hagar overhears the child tell her mother: That horrible, old egg-woman is at the door! The penny drops.

Stunned, she leaves the house and finds her way to a public bathroom where she turns on all the lights and studies her face in a mirror. What looks back is a face she doesn’t recognize, someone pathetically at odds with whom she imagines herself to be. She sees in fact the horrible, old egg-woman that the child saw at the door rather than the young, gracious, attractive, big-hearted woman that she imagines herself still to be. “How can this have happened?” she asks herself. How can we, imperceptible to ourselves, grow into someone we don’t know or like?

In some way, it happens to all of us. It’s not easy to age, to accept the fall from what we dreamed for ourselves, to watch the young take over and receive the popularity and acclaim that once were ours. Like Saul, we can fill with a jealousy that we don’t recognize, and like Hagar, we can grow bitter and ugly without knowing it. Others, of course, do notice.

It’s not that we don’t gain something as this happens. Usually we grow smarter, wiser in the ways of the world, and remain goodhearted, generous people. However, we tend to be nastier than we once were, whine too much, feel too sorry for ourselves, and give ourselves over more to curse rather than bless those who have replaced us, the young, the popular, the acclaimed.

And so, the penultimate spiritual and human task of the second half of life is to give up this jealousy and ugliness and come back again to the love, innocence, and goodness of our youth, to revirginize, move toward a second naiveté, and begin again to admire something.

At the beginning of the Book of Revelations, John, purporting to speak for God, has some advice for us, at least for those of us beyond the bloom of youth: “I’ve seen how hard you work. I recognize your generosity and all the good work you do, but I have this against you — you have less love in you now than when you were young! Go back and look from where you have fallen!”

We might want to hear this from Scripture before we overhear it from some young girl telling her mother that some dour, bitter, old person is at the door.