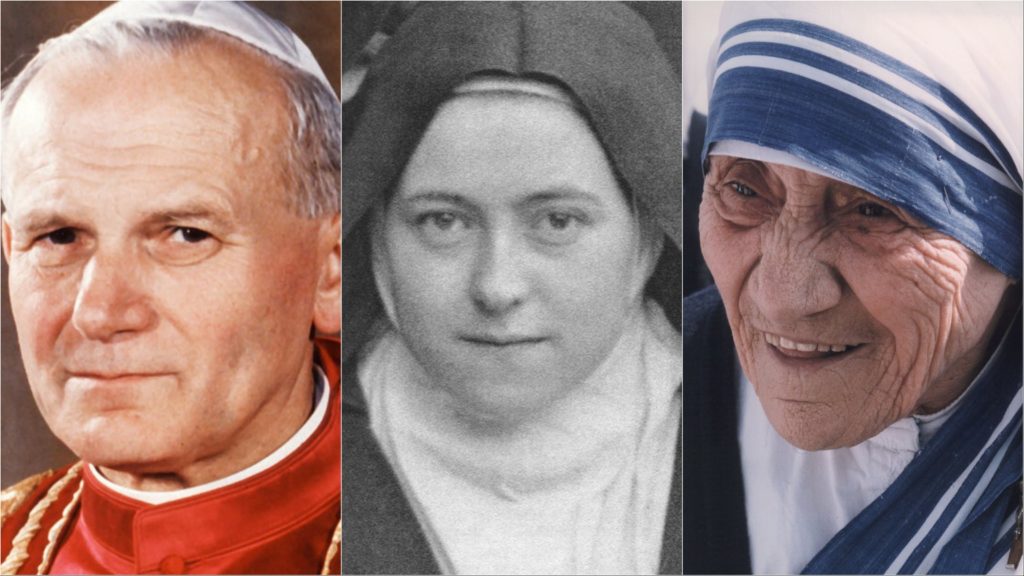

Jan Tyranowski (1900-1947), Catholic layman, served a crucial role as spiritual adviser to the young Karol Wojtyla, who later became St. Pope John Paul II.

An eccentric figure with white-blond hair and a distinctive, high-pitched voice, Tyranowski lived with his mother and several cats across the street from the Wojtylas in Poland.

He worked as a tailor, was voluntarily celibate, and cultivated an intense prayer life, often aggressively trying to recruit the young people of the neighborhood to participate in his “Living Rosary.”

In February 1940, Wojtyla was 27. Tyranowski was 40. The two met at a meeting in a local parish hall. Immediately the future pope was drawn by Tyranowski’s spiritual fervor.

A year later, Wojtyla’s father died. Shattered by the blow, young Karol spent more and more time with Tyranowski. The two endlessly discussed Scripture as well as the mystical writers Teresa of Ávila and St. John of the Cross.

“I must decrease; he must increase,” observed John the Baptist, a truth Tyranowski, bending over his needle and thread, must have known well. A reader of men’s souls, he seemed to have sensed that his friend was destined for greatness and glad to have taken last place himself.

For his part, Wojtyla saw something in the odd little tailor that few others could, and came to value deeply his spiritual guidance.

“Tyranowski was truly one of those unknown saints,” noted Pope John Paul II (now himself a saint), “hidden among others like a marvelous light at the bottom of life at a depth where night usually reigns.”

Then there was Jacqueline de Decker, also known as Mother Teresa’s “Spiritual Powerhouse.”

British journalist Kathryn Spink tells the story in “I Need Souls Like You: Sharing in the Work of Mother Teresa Through Prayer and Suffering” (HarperCollins, $10.35).

Born in 1913, de Decker came from a well-to-do Belgian family. Hoping to work with the Missionaries of Charity, she made her way to India and, in 1947, walked halfway across the country to meet Mother Teresa.

Instead she was forced back to Antwerp by a chronic, debilitating spinal illness. Her dreams shattered, de Decker was devastated.

But in the fall of 1952, she received a letter from Mother Teresa that read in part:

“You have been longing to be a missionary. Why not become spiritually bound to our society which you love so dearly? While we work in the slums, you share in the prayers and the work with your suffering and your prayers. The work here is tremendous and needs workers, it is true, but I also need souls like yours to pray and suffer.”

De Decker proceeded to marshal many of her fellow patients into becoming “Sick and Suffering Co-Workers,” each a link to an individual Missionary of Charity. In turn, Mother Teresa pledged to pray for them.

Encased in a corset, constrained by a surgical collar, de Decker also came to look after the welfare of some 2,000 prostitutes, careening around Antwerp’s red light district in a specially adapted car tending to “her girls.”

Mother Teresa came to call de Decker her “sick and suffering self.” By 1980, she had undergone 34 operations for her illness, which was never officially diagnosed. She herself called it GGD, or “God-Given Disease” — her recognition that emptiness, “failure,” and weakness were the means by which God used her. De Decker died on April 3, 2009.

“Love demands sacrifice,” wrote Mother Teresa. “But if we love until it hurts, God will give us his peace and joy. … Suffering in itself is nothing; but suffering joined with Christ’s Passion is a wonderful gift.”

Finally: How would you like to be the “difficult” sibling of St. Thérèse of Lisieux? The one who couldn’t behave or fit in no matter how hard she tried? The one who didn’t “shine”? The one who failed three times at religious life before succeeding?

Such was the destiny of Servant of God Léonie Martin (1863-1941).

The other four Martin sisters were intelligent, lively, and charming. Léonie, the middle child, was expelled from school, suffered from eczema, and occupied the smallest bedroom at Les Buissonnets, the family home. Even her own mother referred to her as “poor Léonie.”

Thérèse entered the Carmelite convent, died of TB at 24, and left a spiritual memoir that would change the world.

After several failed attempts at religious life, Léonie, by contrast, entered the Monastery of the Visitation at age 35. She followed the path of the “little way” developed by Thérèse — whom she considered her spiritual mentor — was faithful to her vows for 41 years, and died at 78.

She was obscure in life and, eclipsed by her much beloved and world-renowned sister, obscure in death. Then, around 1960, prayer requests directed toward Léonie began coming in to the monastery. People identified with her isolation within the family, her difficulty in finding her vocation, her brokenness, her life of silent prayer.

Her cause for beatification was opened in 2015.

As biblical scholar Anne Marie Pelletier notes: “[T]he Christian life is not an athletic performance!”

“The true Christian life is always a matter of poverty offered to God and transfigured by him.”