Unless you’ve been in a coma these past few months, you’re most likely aware of the “far-reaching and ambitious exploration of Latin American and Latino art in dialogue with Los Angeles” sponsored by the Getty and known as “Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA.”

Through January 2018, there will be photography, video art, performance art, sculpture, painting, workshops, screenings, lectures and concerts. Participants will include more than 70 institutions throughout greater L.A.

In Palm Springs, for example, you could take in, among other exhibits, “Carved Narrative: Los Hermanos Chávez Morado” at Sunnylands Center & Gardens (through June 3, 2018).

In Claremont, you could visit, say, “Revolution and Ritual: The Photographs of Sara Castrejón, Graciela Iturbide and Tatiana Parcero” at Scripps College (through Jan. 7).

Right here in town, you could almost dip a finger into a different event each day. The Getty itself is featuring, among other related exhibits, “Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy of Ancient Americas” and “Photography in Argentina, 1850-2010: Contradiction and Continuity” (both through Jan. 28).

I decided to zero in on “La Raza” at the Autry Museum of the American West (through Feb. 10, 2019).

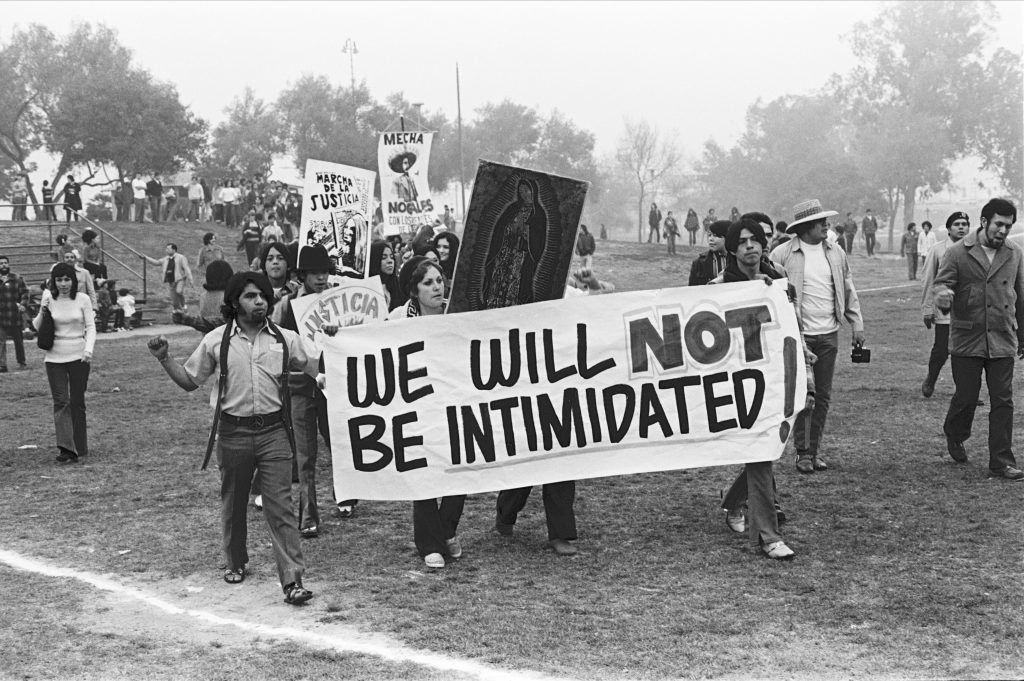

“La Raza” (meaning, roughly, “the people”) was the L.A. newspaper-turned-magazine central to the Chicano Rights Movement of the 1960s and 1970s. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the publication’s founding.

Pioneers in photojournalism, the La Raza staff used art, satire, poetry, political commentary and, above all, photography. They recently dug into their archives and bestowed a stupendous gift upon UCLA’s Chicano Studies Research Center — more than 25,000 images previously inaccessible to the public.

The Autry exhibit features more than 200 of them, digitally printed and mounted, along with compelling text, graphics and commentary. On Oct. 15, I attended a seminar at the museum of three former La Raza photographers.

Joe Razo has a law degree from Loyola and served as editor from 1968 to 1972. He was working as an organizer in Lincoln Heights when he first read a copy of the newspaper and realized he had similar interests — and better research skills. He called the next day, began writing for them and never looked back.

Devra Weber has a Ph.D from UCLA, teaches at Riverside on the history of U.S. frontiers and has authored or collaborated on several books. As a young graduate student studying working-class history, she began at La Raza by doing layout and taking photos in East L.A., eventually becoming a valued staff photographer.

Raul Ruiz was a photographer and editor at La Raza from 1969 to 1977. He joined as a student in Latin American studies at Cal State L.A. He now has a Ph.D. from Harvard and is professor of Chicana/o Studies at Cal State Northridge.

As a college student, Ruiz observed, he thought history was for “other people.”

“We had a poor self-concept,” Razo continued. “Our men were portrayed in movies and TV as gangbangers and criminals. Our women were ‘hot tamales’ with castanets. There was a rich cultural legacy that was not being taught. Without role models or self-concepts, our kids were angry, hostile, frustrated.”

“El Movimiento” — the Chicano Movement — began, in fact, with an effort to improve the education available to the Latino community. The idea was to focus the anger, the drive, the motivation exteriorly on the institutions — police, schools — that discriminated.

To witness these veterans of the movement, still vital, with senses of humor intact, swapping anecdotes and trading war stories, was to see the history of our city come alive.

rn

rn

rn

La Raza staff member Maria Varela in Denver, Colorado, 1969. (COURTESY OF UCLA CHICANO STUDIES RESEARCH CENTER / © LA RAZA STAFF PHOTOGRAPHERS)

They spoke of the primary role of women in the movement. They remembered the East L.A. walkouts of 1968, when students rose up against unequal conditions in LAUSD high schools.

Particularly gripping was the story of the police killing of L.A. Times journalist Ruben Salazar during the National Chicano Moratorium March against the Vietnam War on Aug. 29, 1970.

As for the exhibit itself, 50 years later, the art, layout and colors of the magazine covers are still boldly compelling. Tension runs like an electric current through the images of demonstrations, marches, picket lines and an overwhelming, combat-ready police presence.

Sections include “Signs of the Times” (banners, posters, flags, graffiti, murals), “The Other and the State” (surveillance as a form of control) and “The Body” (physical damage caused by LAPD aggression).

A central, interactive touchscreen table provides access to 12,000 additional images from the full La Raza archive. The day I visited, a lively group of gray-haired friends were poring over it, exclaiming every so often, “Hey man, that’s Ricardo!” or “Damn, I remember that street corner!”

With all that, it was “Portraits of a Community” — weddings, parties, funerals — that to my mind brought the era deeply alive. A mariachi band. A beauty parlor. A couple of classy old gents — suits, canes, fedoras — sitting on a Soto St. bench.

Perhaps my favorite image was of a dreary institutional hallway where, beneath a sign reading Central Jail, a young Latino couple stole a clandestine, exultant embrace. Had someone just made bail? Whatever the backstory, you just knew the two were about to say, “Let’s get out of here, call some friends, cook a feast, crack open some beers and start dancing.”

La Raza. The people.

Heather King is a blogger, speaker and the author of several books.