Richard Flanagan, Booker Prize-winning novelist, was raised and lives in Tasmania.

His new book, “Question 7” (Knopf, $28), takes its title from a metaphysical puzzle posed in a short story by Russian writer Anton Chekhov:

“Wednesday, June 17, 1881, a train had to leave Station A at 3 a.m. in order to reach Station B at 11 p.m.; just as the train was about to depart, however, an order came that the train had to reach Station B by 7 p.m. Who loves longer, a man or a woman?”

Chekhov’s point is that the writer’s job is to ask the deepest questions without purporting to answer them.

In a family memoir that weaves together the romance between H.G. Wells and Rebecca West, the development of the atom bomb, and his father’s internment as a Japanese POW, some of the questions Flanagan asks include: Who owns the truth? Is there a final accounting? If there’s no one left to remember that a particular incident happened — the brutal torture inflicted by a group of camp guards; the incineration of a city and its people — does that mean the incident never happened?

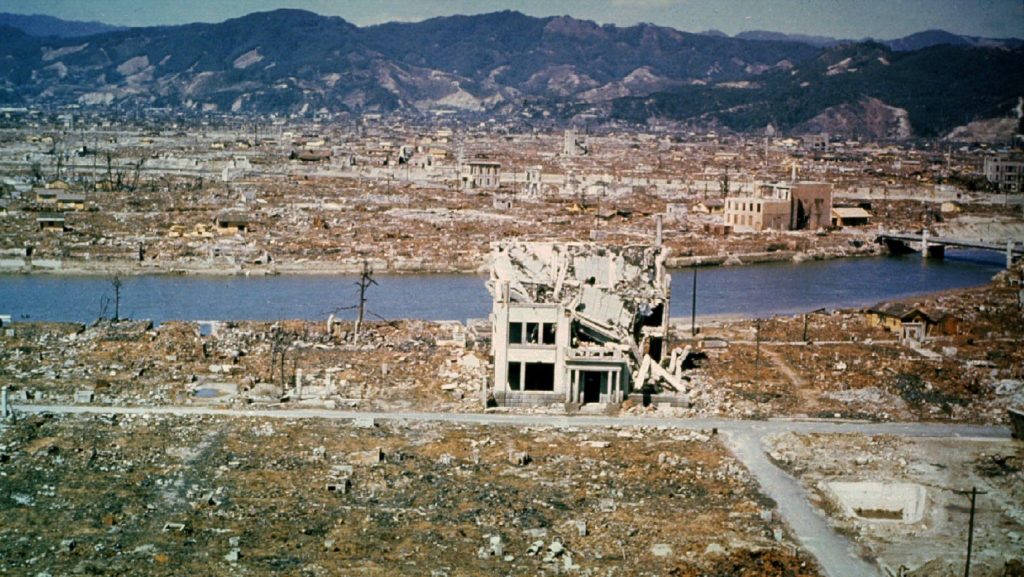

On the morning of August 6, 1945, U.S. Army Major Thomas Ferebee released “Little Boy” — the largest man-made explosion in human history — on the civilians of Hiroshima, and went on his way, sleeping well that night and to the end of his life, expressing not a shred of remorse.

He did have one qualm that morning: Would he still be able to have children? Unlike the approximately 120,000 Japanese who died that morning and the tens of thousands more who suffered for years with radiation poisoning, leukemia, and/or third-degree burns, he was able to and had four sons and five grandchildren.

“Is it because we see the world only darkly that we surround ourselves with lies we call time, history, reality, memory, detail, facts?” Flanagan asks. “Do possibly more corpses tomorrow justify possibly fewer corpses today?”

“If it is a question that can never be answered, it is still the question we must keep asking.”

As Flanagan grows up, his own father is a beneficent presence: mostly (and understandably) silent, enigmatic, alone. He seems to have “passed through something” and spends a lot of time in his office. He’s repelled, however, at the thought of violence or vengeance. “War is an obscenity,” he tells his son many years later.

Flanagan doesn’t point fingers exactly. He simply points out the facts. We can do with them what we like. We can wish those we see as wrongdoers harm in the afterlife. We can realize that we, too, have hurt people, knowingly or unknowingly, and gone on with our lives. We’ve failed people. We’ve not been heroes when we’d hoped we might be.

The book, Flanagan observes at one point, is a love letter to his parents. He also admits that when they became elderly and incapacitated, and asked him to be their full-time caretaker, he refused.

The book, Flanagan observes at one point, is a love letter to his parents. He also admits that when they became elderly and incapacitated, and asked him to be their full-time caretaker, he refused.

In a masterful, nail-biting chapter in the book’s last section, he describes being trapped in a kayak when he was 21.

The boat was wedged between rocks, with tons of water bearing down. He was there for hours, while a friend, P--, courageously, valiantly, tirelessly, dove down again and again into the raging water trying to dislodge it. At the eleventh hour, when the two were both at the tail end of their strength, the kayak, miraculously, moved an inch … then on the next try, another inch, and so Flanagan had in one sense died — “should” have died — and yet lives.

You might think the two would remain lifelong friends — but no. They barely speak after that day.

In a way, that story is a counterpart to an earlier one in which Flanagan travels to Japan to revisit the site of the slave labor camp where his father had also almost died. Nothing remains. The villagers, friendly and warm, remember nothing. Mr. Sato, a former guard, is an old man now, shrunken, frail, and cares for a disabled daughter.

No act of evil can ever be undone, Flanagan seems to be saying; no penance can erase it.

Moreover, simply to be alive means that we have elbowed out or benefited, consciously or unconsciously, willingly or unwillingly, from the suffering or death of any number of people.

If H.G. Wells hadn’t written the novel “The World Set Free,” Hungarian physicist Leo Szilard might never have become obsessed with how to create and patent the nuclear chain reaction that made possible the atomic bomb.

If the bomb hadn’t been dropped on Hiroshima, the war may not have ended when it did, the POWs may not have been set free, Flanagan’s father wouldn’t have made his way home to Tasmania, nor married his mother, and he, Richard, wouldn’t have been born.

So is that chain of events good or bad? Who can say? And yet “Question 7” is a book of hope.

The brutal camp guard may have had selective amnesia but on another occasion, three Japanese women came to his father with gifts, asked him to tell his story, and listened.

At the end of this “strange ceremony,” weighed with “dignity and goodness, the women — who were not personally responsible but had taken upon themselves the burden of exposing Japanese war crimes — said they were sorry.

“I could never have believed that saying sorry could mean so much.”

Why do we do what we do to each other? Who loves longest?