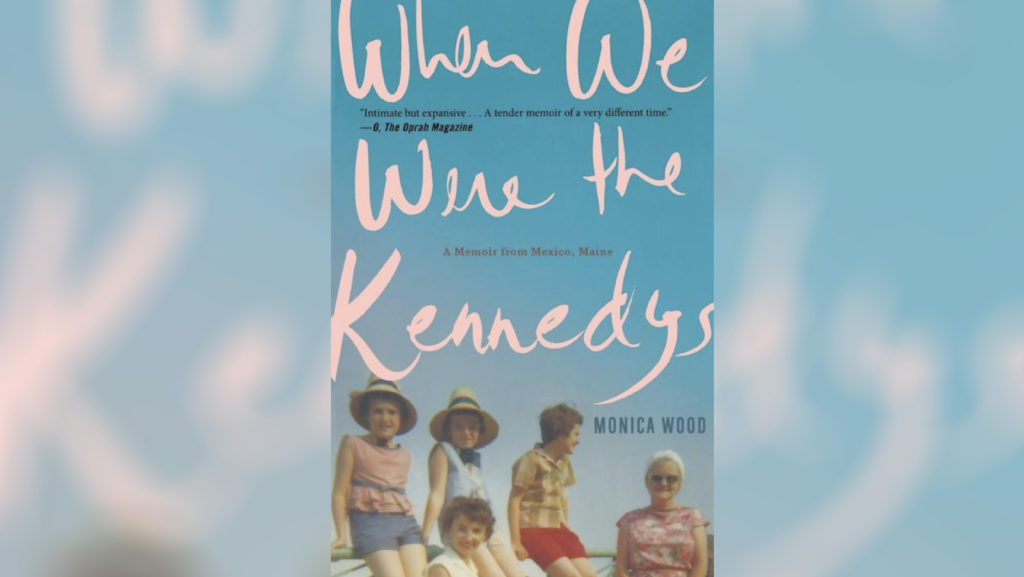

“When We Were the Kennedys: A Memoir from Mexico, Maine” (Mariner Books, $14.95) is the story of a Catholic, blue-collar childhood; of the trauma of losing a parent early, of love of family and place, and of forgiveness.

It’s a perfect book, in other words, for Christmas.

Written by New York Times best-selling author Monica Wood, the book begins in April, 1963.

Towering over the town of Mexico, Maine, and its adjacent, larger neighbor, Rumford, was what residents called “the mill”: the Oxford Paper Company. “That boiling hulk on the riverbank,” Wood describes it, “the great equalizer that took our fathers from us every day and eight hours later gave them back, in an unceasing loop of shift work.”

If Oxford Paper was Mexico’s North Star — for a time at least, a beneficent God — Albert Wood — “loose with laughter, physically tough, a natural lightheart” — was the patriarch and North Star of the author’s family.

He and Mrs. Wood have five children. Two are older: Barry, 27, married with children, lives nearby. Anne, the oldest daughter, at 21 is already ultra-conscientious, daintily beautiful, and teaching Spencer’s “The Fairie Queen” at a local high school.

Then had come three late-life daughters: Betty, mentally disabled, Monica (Monnie), and Cathy, the youngest.

All three attend St. Theresa’s, a local French Catholic elementary school. They eat their oatmeal each morning with a resident parakeet perched on the rim of their bowl and a tabby twining between their legs, as their mother presses their uniforms piece by piece at the ironing board, sending them off with starched collars, neatly pleated skirts, and their lunch bags.

The town is a melting pot: French, Italian, Polish. Their father has brought his heart, his work ethic, and his lilting phrases from Canada’s Prince Edward Island: “Desperate-handsome,” “For crying out gently,” “Fearful-grand.”

They live on the third floor of a triple-decker apartment house. On the ground floor are their scrimp-and-save landlords the Norkuses, Lithuanian refugee/immigrants. “Make stop you jump!” they yell at the girls who constantly run up and down the stairs, and “No bring friend!”

As the story opens, Monnie is in fourth grade, Cathy and Betty are in second. They’re getting ready for school one morning when the news comes: their father has died in a neighbor’s driveway, felled instantly by a heart attack.

The memoir constellates around this unthinkable, unspeakable loss. “I’ve lost my best friend!” keens their mother, and spends several months in bed.

The family is shattered, forever, but somehow they keep going. Anne is their guiding light. The neighbors bring tuna casseroles, soda bread, offers of help.

Denise Vaillancourt, whose parents welcome Monnie to their own crowded table, becomes a lifelong friend.

Then there’s Father Bob, their mother’s brother, who wears his collar and “blacks” wherever they go. The girls burst with pride when Father visits their classroom: Toll booth collectors wave them through: “Go right ahead, Father, no charge.”

Their lives are shot through with the Church’s angels, saints, and prayers, its quirks, its rituals, and rules.

“Like most Irish Catholic families in 1963, mine had a boiled dinner on Sundays after Mass and salmon loaf on Fridays. We had pictures of Pope John and President John and the Sacred Heart of Jesus hung over our red couch… We went to Mass on Sundays and high holy days, singing four-part Tantum Ergos from the choir loft.”

On overnight visits to the rectory, Father Bob says a private Mass for “his girls.”

Afterward, “we’d rush the sacristy to watch him shed his vestments, smooth out their gilded folds, and hang them in a closet made special. He stashed the chalice and paten. Everything so tidy, so proper … we learned the after-Mass protocol the way children in other places learn to trim a sail or wax their skis.”

Betty is neither sentimentalized, nor indulged, nor immune from teasing. She’s simply a cherished member of the family, accepted and accommodated without question, without comment.

When J.F.K. is assassinated the same year their father dies, their mother feels an instant sense of identification. Jackie, Caroline, and John-John have also lost a husband and father. Jackie, too, bravely attended the funeral Mass, well-behaved children in tow. The extended Kennedy family, like the Woods, even have a child with Down syndrome.

So deep is “Mum’s” imagined bond with the Kennedys that she marshals the whole family to take a road trip to Washington, D.C. En route, they stop in Baltimore to pick up Father Bob, who it turns out has been in a Catholic hospital drying out: “Just nervous,” Mum smooths over his alcoholism.

“The Catholic tradition of my childhood — which I recall with affection, some awe, and a measure of yearning — did not allow for randomness. … Wherever you fit into the plan — giving Communion or receiving Communion; top of the class or mentally retarded; working or on strike; whole and happy or hacked to pieces by grief — you fit. That was the Plan’s cruel beauty. You wept if you had to, hid your face and gnashed your teeth, but you knew that if you repaired to your bed of pain it was because God wanted you there — only you, only there — to complete the unknowable requirements of something great and vast and ultimately beautiful.”

“Believe it or not, this was a comfort.”

It still is.

Merry Christmas.