As Christ observed, “There are many rooms in my Father’s mansion” (John 14:2).

Thank heaven for that.

The communion of saints includes movers and shakers, the organizers, the administrators, the top ecclesiastical guns. There are the nuns who founded orders, built convents, and changed the face of education or health care. There are the martyrs, the stigmatists, and those who persevere through severe physical disabilities.

And every once in a while, there’s a figure so tragicomically out of step that I begin to believe there’s hope even for me.

One such person would be Servant of God John Bradburne (1921-1979), Third Order Franciscan, missionary and poet, who worked with lepers in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and was murdered by guerillas near the end of the country’s 15-year civil war.

Born to an Anglican vicar and his wife in Cumberland (now Cumbria) County, England, Bradburne was baptized into the Church of England and served with the Indian Army during World War II in India, Malaya, and Burma.

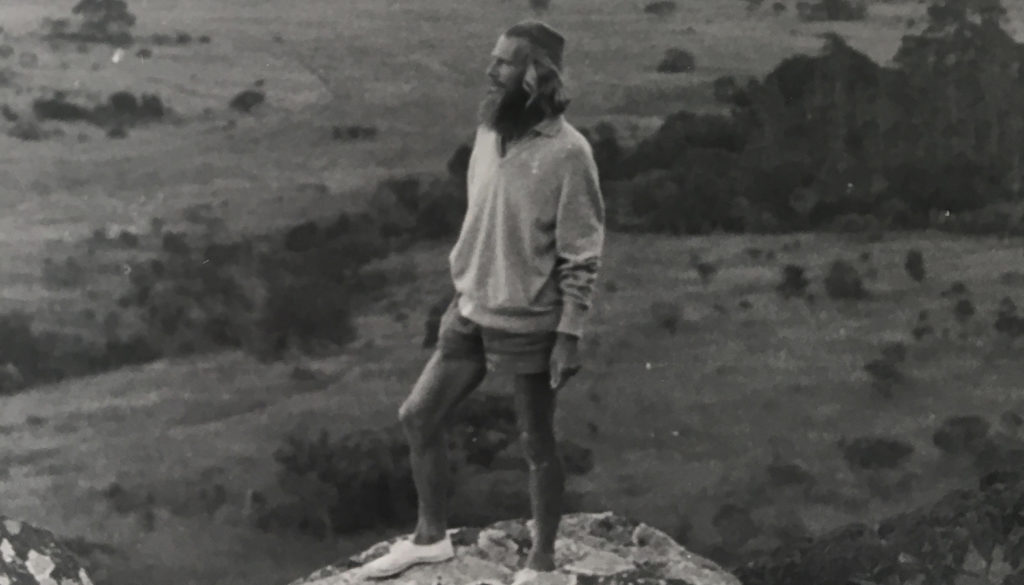

A seeker, dreamer, and wanderer with a generous heart and few practical skills, he was deeply drawn to silence and solitude. During the war, faith became the dominant impulse in his life. He also met the future Father John Dove, SJ, who would play a decisive role in Bradburne’s life.

He returned to England after the war, staying with the Benedictines at Buckfast Abbey. There, he converted to Catholicism and was received into the Church in 1947.

Bradburne had no interest whatsoever in politics, social issues, or current events. He longed to become a monk at Buckfest, but on the eve of taking vows, he fell madly in love with an older woman, panicked, and simply fled.

In the biography, “Strange Vagabond of God,” Dove charts Bradburne’s subsequent nomadic existence. He wandered through England, France, Italy, Greece, and the Middle East, often on foot, carrying his belongings in a small bag with almost no money.

He tried, and failed, to join the Benedictines in England, the Carthusians in Israel, the Order of Our Lady of Mount Sion, and an abbey in Belgium.

He visited the Holy Land twice, lived for a year in the organ loft of a tiny church in Italy, and for a time served as caretaker of Hare Street House in Hertfordshire, the former residence of Catholic writer Robert Hugh Benson.

Bradburne never learned to drive and had few practical skills. He played plainchant on the harmonium and recorder, loved birds, decorated his living quarters with feathers and pebbles he found on his walks, and ate but once a day. With more than 170,000 lines of verse, he holds a Guinness World Record as the most prolific poet in English.

He could also be prickly, especially when noise and people intruded too heavily on his solitude.

In 1953, Bradburne took a private vow to Our Lady never to wed and consecrated himself to a life of celibacy.

On Good Friday 1956, he joined the Secular Franciscans.

In 1962, he wrote Dove, asking “Is there a cave in Africa where I can pray?” Then he rambled around Africa for seven years before arriving in 1969 at the Mutemwa (meaning, “You are cut off”) Leper Colony in Rhodesia, 90 miles northeast of the capital of Harare.

The conditions were abysmal, but Bradburne enlisted help from a nearby Catholic mission and tenderly cared for the abandoned residents: washing, bandaging, and bathing, as well as burying the dead.

After all that, he tangled with the local Leprosy Association and, in spite of his devoted service, was kicked out. For the last six years of his life, he lived in a tin hut just outside the enclosure’s perimeter, sweltering in the heat and continuing to minister to his beloved “family.”

Dove notes that Bradburne was a profoundly affectionate person “who was seldom fully understood and always gave more than he received, often to his cost in heart and spirit, and even in material goods. He would give his all to those he loved, as indeed he did at the end, with his life.”

The Rhodesian Bush War (also known as the Zimbabwe War of Independence) lasted from July 1964 to December 1979, and pitted the white minority ruling government against two African nationalist parties.

As the war neared its conclusion and approached the leper colony, several lay and Catholic aid workers and missionaries were killed by guerillas. Bradburne’s friends urged him to leave, but he refused.

He was abducted on Sept. 3, 1979, and while kneeling in prayer two days later he was shot in the back.

During the course of his life, he had developed three wishes: to help the victims of leprosy, to die a martyr, and to be buried in the Franciscan habit.

He was granted all three.

His cause for beatification was opened in September 2019. A true child of God, he had once noted: “I am so useless, and clueless and un-illustrious. That makes me more truly confident in the power and guidance of the Holy Spirit.”