Eighth in a series on the Book of Psalms.

Because they were songs, the psalms served as the most useful means of transmitting culture. They were memorable, and so they were easily quotable.

Philo of Alexandria, the great Jewish scholar of the first century A.D., quotes the “Psalter” more than any other book in the Bible, except for the books of the Law. In the New Testament, references to the psalms even surpass references to the Torah. All told, 103 out of 150 psalms appear in the pages of the New Testament, and many are quoted more than once.

Jesus’ self-understanding draws deeply from the psalms. The Letter to the Hebrews portrays him as quoting the psalms at the very moment of his incarnation: “When Christ came into the world, He said, ‘Sacrifices and offerings you have not desired, but a body you have prepared for me; in burnt offerings and sin offerings you have taken no pleasure.’ Then I said, ‘Lo, I have come to do your will, O God,’ ” (Hebrew 10:5–7; Psalm 40:6–8).

In the last agony of his earthly life, Jesus quoted the psalms twice from the cross: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me” (Matthew 27:46; Psalm 22:1) and “Father, into your hands I commend my spirit” (Luke 23:46; Psalm 31:6). In between that first moment and the last, Jesus invoked the psalms at key events in his ministry, including his temptation in the desert and the Sermon on the Mount.

The psalms remained important to the early Christians. Pope St. Clement I, writing as early as A.D. 67, cited the psalms almost 50 times in the course of a single letter!

Many of the Church Fathers wrote commentaries on the psalms; Origen and St. Jerome may have written three apiece. St. Gregory of Nyssa reported that, in the fourth century, the psalms were sung everywhere and by everyone — “whether walking, at sea, or engaged in sedentary activities … [by] men and women, healthy and ill.” St. Jerome wrote that, in his day, farmers in the fields sang the psalms while they were working.

Nevertheless, St. John Chrysostom was still able to complain that “those singing it daily and uttering the words by mouth do not enquire about the force of the ideas underlying the words.”

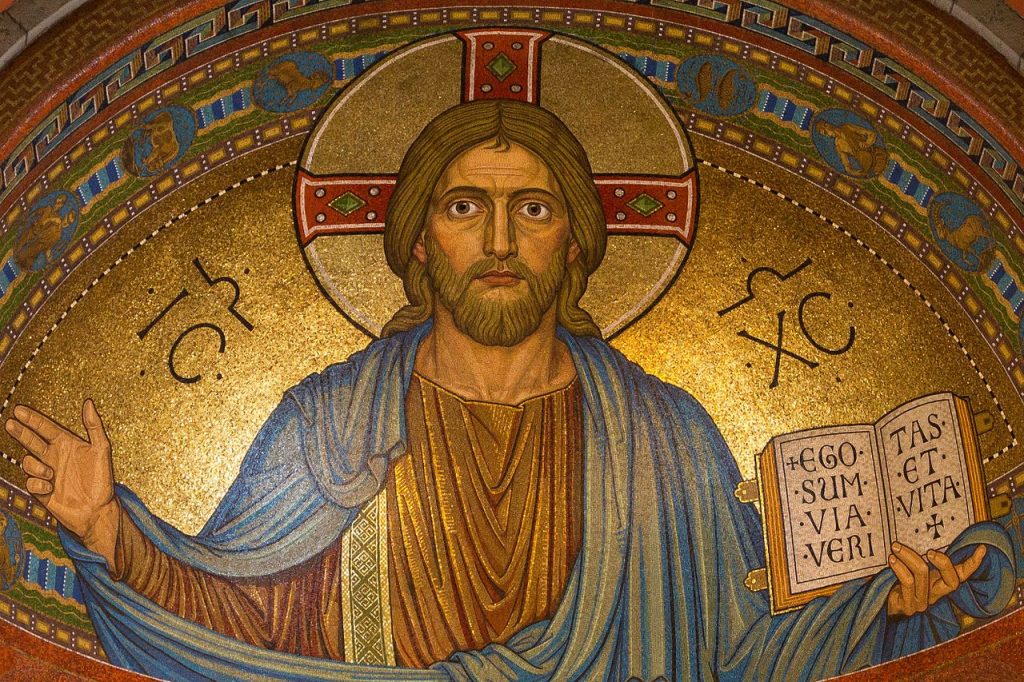

What were those underlying ideas? For the early Christians, the psalms were about Christ; he was the main character in the book. Spiritual writers would see him present in the psalms on several levels: the psalms were the prayers of Christ; they were prayers to Christ; and they were prayers about Christ. But, if Christ was the character, what was the story? What was the big idea?

The story we’ve been trying to discern — the story within the “Psalter” — was the same for God’s chosen people, the Jews, as it would be for the Church. It’s the story of the Covenant, and we’ll talk more about that in our next column.