“The Glacier Priest” (University of Notre Dame Press, $38), a biography of Father Bernard Hubbard, SJ, by Josh McMullen, paints a portrait of a creative and energetic personality whose ministry greatly affected the Church in the United States, but who remains largely unknown.

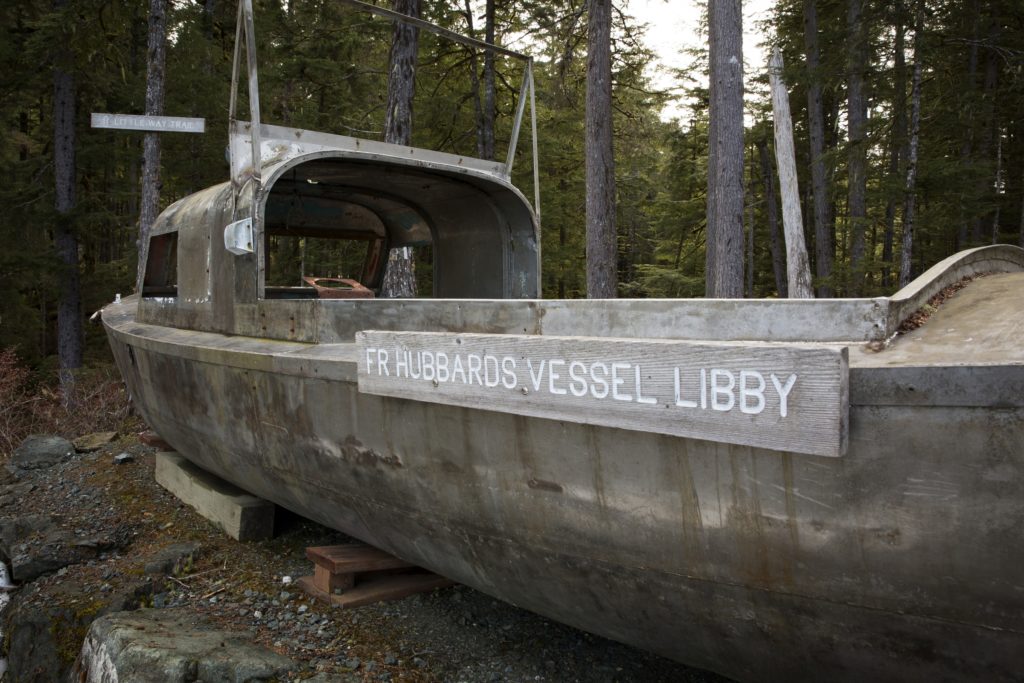

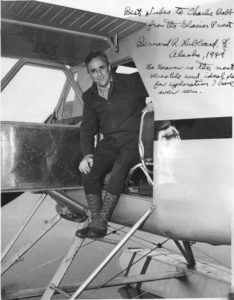

A geology teacher at Santa Clara University, Hubbard was also a famous photographer, explorer, and lecturer who, using books, movies, journalism, radio, and television, reached millions through his talks about Alaska. From the 1930s until his death in 1962, he helped to craft the state’s history and mythology. The Catholic Church in Alaska could still use someone like him raising funds.

His story is as colorful as his super-sized personality. The priest crossed glaciers and climbed mountains and volcanoes. He hiked, flew, and dogsledded across the most difficult terrain, many times risking his life.

Blizzards, melting ice, pumice pits, below-zero weather, wild animals, problems with the team for the dogsled, lost food supplies — all of these were extreme challenges he faced. No wonder Hubbard attempted to make a commercial movie of his adventures, although it never competed with “Nanook of the North” for box office appeal.

His talent as a storyteller as well as his slides — and sometimes his dogs used as props — made him a popular and entertaining lecturer.

McMullen writes that Hubbard created a persona, the “Glacier Priest,” and his exploits made him a hero. The Young Catholic Messenger magazine published a comic strip celebrating his adventures. He also wrote three books, developed hundreds of short films, and took more than 200,000 pictures, which were published widely with his articles. He was a celebrity as well as a teacher and priest.

Hubbard thought of himself as an explorer like some of the heroes of his Jesuit order. His message was not just geology and geography, but virtue and endurance. His subplot was always the wilderness as the locus of bravery, and strength and humility versus the false, materialistic values of what he called “chiselization.”

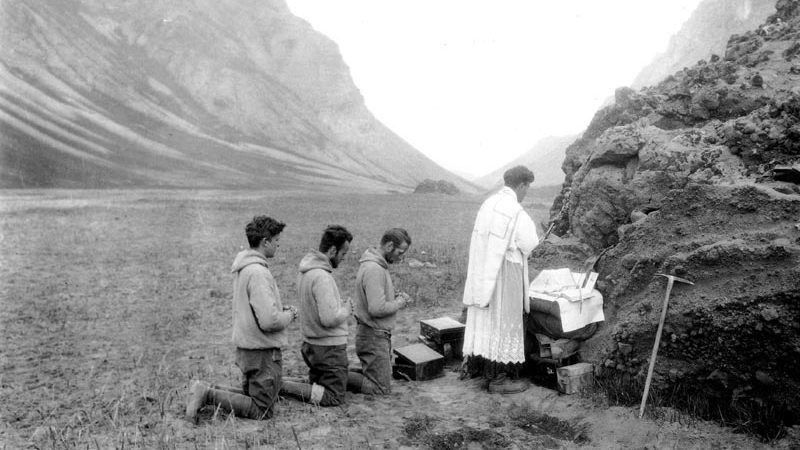

At the same time, he was a devout priest of the traditional Jesuit spirituality. He said his Mass on a makeshift altar in the snow in the open air, with a certainty that Christ the King of the Universe was made present to the wild beauty of the wilderness. He said his breviary by the campfire, and his soul saw poetry in the untamed Alaskan landscapes.

He loved his husky dogs, once kissing and hugging them after a narrow escape from a mishap on the sled. But he took that love to a sometimes bizarre extreme: He had two of his favorite dogs from his sled teams stuffed and kept them around. Tenderness as taxidermy.

McMullen tells of Hubbard growing up in a devout Catholic family. His father was a fervent convert from Episcopalianism (an odd thing since he was a descendant of French Canadians, but McMullen does not explain the rarity). Hubbard’s vocation to the Jesuits meant enduring the rigorous training of his time, which included for him an extra-long period before Holy Orders.

Sent after World War I to study theology in Innsbruck, Austria, he experienced not only a different culture but also the post-war scarcity of the time. Always generous, and always proactive, while he was in seminary he raised money for the Passion Play for Oberammergau when a lack of funds threatened its production.

In Austria, he fell in with the dethroned Hapsburgs and formed a lifelong friendship with the former Crown Prince, Otto.

I enjoyed “The Glacier Priest” because it brought to my attention a priest with extraordinary talents and a breadth of experience, and aspects of American Catholic history I knew nothing about. There are so many unwritten chapters on that subject, and this book fills in some of the blank spaces on the map, like Hubbard did with his Alaskan explorations.

McMullen’s writing is sometimes a bit term-paper-ish, and some of his generalizations about Catholic culture and American history seem stretched. His concentration on Hubbard contributing to a positive image of Catholic priests in a sometimes hostile Protestant culture, somehow precludes mentioning other contemporary famous clerics like Archbishop Fulton Sheen, Father Edward Flanagan (of Boys Town fame), Charles Coughlin, and Father Daniel Lord, SJ.

McMullen makes clear Hubbard was the subject of his own entrepreneurship — the explorer extraordinaire, a one-man priest as superhero franchise. His superiors were worried about his humility, and McMullen provides a lot of evidence in their favor.

He was not above dramatizing even some of the real dangers of his explorations. The author lets slip a typical biographer’s ambivalence describing Hubbard’s ego: “…[He] often agreed to things without thinking them through, especially if they expanded the influence of the Glacier Priest.”

McMullen’s work made me feel that I know Hubbard — and glad that I do. I have much less sympathy with his critics, because I agree with Hubbard that envy is endemic in some clerical circles.

The book reminded me of Jack London’s stories of Alaska. Hubbard admitted being inspired by “The Call of the Wild,” although his philosophy was far from London’s. They certainly both loved their canines.

One London story in particular connects with themes of Hubbard’s ministry. “The Story of Jees Uck,” narrates the spiritual nobility of a woman of mixed blood, who has a child by a rich American, Neil Bonner, who had been punished by his father and sent to work in a trading post of the family’s company.

Neil leaves her when he hears of the death of his father, swearing, of course, to return. London observes that even he believed he would. He was unaware of her pregnancy. Jees Uck never stopped believing in Neil. After giving birth and refusing other men’s proposals, she makes her way to him in an odyssey from Alaska to San Francisco, with her child, only to meet his new wife and their daughter. In a decision that London calls a great renunciation, she decides not to make trouble, and goes back to Alaska, the rich American wife no wiser.

The son, named after his father, is sent away by a French missionary to be educated and eventually becomes a Jesuit himself. “And in the end there returned to Alaska one Father Neil, a man mighty for good in the land, who loved his mother and who ultimately went into a wider field and rose to high authority in the order.”

The story has Alaskan history, the wilderness and the weather, the cultural tensions of the indigenous people and the brave pioneers, and the Jesuit missionary effort all rolled into one. There is even a dog. If Hubbard never read the story, it is a shame.