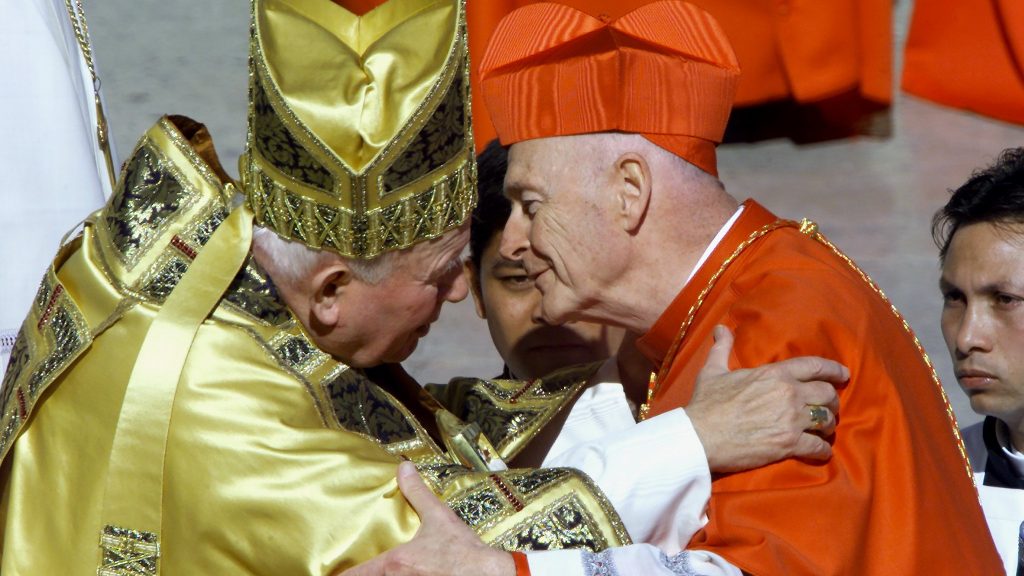

In the wake of the Vatican’s explosive report on Theodore McCarrick, the ex-cardinal and ex-priest brought down two years ago by revelations of sexual abuse and misconduct, some observers say the report “taints” the legacy of St. Pope John Paul II because he’s the pontiff who promoted McCarrick despite confidential warnings about his behavior.

The report shows that when St. John Paul named McCarrick to the Archdiocese of Washington, D.C., in 2000, he had a letter from the late Cardinal John O’Connor of New York outlining various accusations made against McCarrick, including claims of sexual advances to priests; anonymous charges of pedophilia; and reports of sharing his bed with young adult men, including seminarians.

Nonetheless, St. John Paul chose to overlook those concerns and put McCarrick in Washington, positioning him to expand his reach and influence for the next 20 years.

So, is that enough to steal St. John Paul’s halo?

To begin with, there’s no indication that St. John Paul actually believed McCarrick was a predator and promoted him anyway. Instead, the record suggests that the pontiff allowed himself to be convinced, for a variety of reasons, that the claims against McCarrick were unsubstantiated, potentially even malicious, and gave him the benefit of the doubt.

Moreover, if the report taints St. John Paul’s memory, then-Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI and, for that matter, Pope Francis, have to take some hits too.

The report shows that under Pope Benedict, the Vatican received renewed reports of misconduct by McCarrick — at that stage, it didn’t involve abuse of a minor — and appealed to him to withdraw from public life to avoid scandal, though without concluding he was guilty. That appeal, however, was largely ignored by McCarrick and no one ever did anything to enforce it.

As for Pope Francis, the report largely sets aside the claim by Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, the former papal ambassador in America, that had personally briefed the new pontiff on the charges against McCarrick in 2013, saying “no records support Viganò’s account.” Pope Francis never saw any of the documentation in the case prior to 2018, according to the report, and neither Pope Benedict nor Canadian Cardinal Marc Ouellet, prefect of the Congregation for Bishops, ever discussed the case with him.

Yet the fact remains that the report says both Italian Cardinal Pietro Parolin, the Vatican’s secretary of state, and then-Archbishop Angelo Becciu, at the time the “sostituto,” effectively the pope’s chief of staff, did discuss the concerns about McCarrick and indications given to him earlier. Yet, the report demonstrates, Pope Francis believed the charges had been settled by St. John Paul and Pope Benedict, and didn’t launch any investigation of his own until the public scandals of 2018.

In other words, it wasn’t just one pope who dropped the ball in some way, but three.

Moreover, these decisions weren’t being made by popes in isolation. The report also shows how bishops both in the United States and in the Vatican, at critical junctures, repeatedly insisted on giving McCarrick the benefit of the doubt, and how McCarrick’s own denials often overrode any claims to the contrary.

To put the conclusion into a soundbite: If the McCarrick report taints a legacy, it isn’t so much that of St. John Paul or any other single individual, but rather an entire clericalist culture in which bishops are taken far more seriously than laity or rank-and-file priests and religious.

In that October 1999 letter by Cardinal O’Connor, which was addressed to the papal ambassador at the time, Colombian Archbishop Gabriel Montalvo, Cardinal O’Connor suggested that if Archbishop Montalvo wanted to get to the bottom of things, he should talk to a lawyer who had worked with McCarrick, a layman named Tom Durkin, and to a priest psychologist named Msgr. James Cassidy, who’d consulted the psychiatrist treating a couple of priests who reported being victimized by McCarrick.

The report shows neither man was ever consulted. Instead, the Vatican relied entirely on the opinions of other bishops in reaching its conclusions.

A similar pattern repeated itself at other important moments in the saga. A bishop would bring damning accusations to the attention of a Vatican official. In assessing them, other bishops would be asked for their opinion, most of whom urged caution and voiced doubt about McCarrick’s guilt. What usually tipped the scale was McCarrick himself, who offered unfailingly persuasive denials.

In other words, it was a conversation about a bishop carried on exclusively by other bishops, with anyone outside the club relegated to the sidelines. If you’re looking for the “bad guy” in this story, that culture quite probably is the most compelling candidate.

Pope Francis has created new mechanisms for reporting and investigating alleged offenses by bishops, including both the crime of abuse and its cover-up, intended to make sure that those voices outside the episcopal club are taken seriously. Time will tell if they work as advertised, but the importance of making such a reform effective is, arguably, the most important conclusion of all from the report.

None of this is to suggest there isn’t individual responsibility, too, and that’s going to be parsed by historians and prosecutors alike. Just within the last few days a Polish member of the European Parliament has called on prosecutors in Kraków to open a probe into the role of Cardinal Stanislaw Dziwisz, St. John Paul’s right-hand man, in covering up sex abuse crimes, and such an inquiry theoretically could fold in Cardinal Dziwisz’s role in the McCarrick case. Other figures in the story could come in for similar attention.

Yet a fair reading of the record would seem to suggest that this wasn’t just a couple of bad actors making decisions based on craven motives. Instead, it seems generally that decent people were hoodwinked by a master manipulator, who got away with it because those in charge were wearing blinders imposed by a culture that said bishops are to be trusted, and everyone else taken with a grain of salt.

Until that changes, simply putting a couple of figures in the dock won’t solve the underlying problem. If it took the Vatican two years and 461 pages to produce a report that hammers home that conclusion, then it will have been time and ink well-spent.