What with 2020 at our doorstep, an exhibit sub-themed “A Fresh Look at Utopia” seems apropos.

Through Feb. 24, 2020, at the Huntington Library and Gardens in San Marino, “Beside the Edge of the World” features new work by five individuals: writers Robin Coste Lewis and Dana Johnson, and artists Rosten Woo, Nina Katchadourian, and Beatriz Santiago Muñoz.

Each spent a year exploring the institution’s library, art, and botanical collections to create works that make up the exhibition’s content.

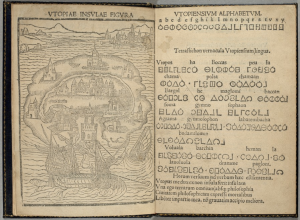

As their point of departure the five artists took St. Thomas More’s “Utopia,” (1516), “a truly golden little book,” as he described it, about a mythical ideal island. (The Huntington owns a first edition, complete with map).

A satire of politics, society, and religion, More considered such perpetually relevant topics as the tendency of kings to start war, squander money, and create poverty in the working classes due to greed.

The name utopia comes from the Greek, meaning “no place,” or more popularly “nowhere.”

An introductory essay by Jennifer A. Watts, the Huntington’s curator of photography and visual culture, points out that in 1919, when Henry and Arabella Huntington signed the trust for “a 600-acre idyll filled with literary and historic treasures, British paintings, French decorative arts and exotic plants as a center for art and scholarship,” the East Coast intellectual elite still regarded Southern California to be “nowhere”: a cultural wasteland filled with slackers, pipe dreamers, and the upstart nouveau riche.

I guess we showed them!

I started with Beatriz Santiago Muñoz’s video installation, “Laurel Sabino y Jagüilla.” Her quest, which I pieced together from the wall commentary and an adjacent vitrine, was to find samples of two endangered Magnolia species indigenous to her native Puerto Rico. Muñoz filmed in the Puerto Rican rainforest and in the gardens of the Huntington itself.

The film has neither credits, beginning, nor end. People, mostly women, walk through the forest clearly intent on searching for a particular kind of leaf but also resting, wondering, and ruminating. They speak in Spanish and subtitles appear.

I braced for preciousness but in fact loved the film. “At the level of forest, older trees give communication to younger ones.” “Plants have poetry that we don’t understand well.” “It waits. Enough. Like that. Period.”

The background noises of dripping water and birdsong were as well wonderfully soothing. “Everything is leaf,” observed Goethe, the 18th-century German writer noted for his treatises on botany, anatomy, and color.

If you think of the perpetually-being-born infant Jesus in the womb of Mary as a “leaf” of sorts, not to mention actual leaves and trees and everything they do and stand for, you kind of have to agree with him.

Dana Johnson’s short story, “Our Endless Ongoing,” is based on the life of Delilah Beasley (1867-1934), American historian, author, and one of the first African American women to be published regularly in a major metropolitan newspaper: she was a columnist for the Oakland Tribune. In “The Negro Trail-Blazers of California” (1919), Beasley gave face and voice to California’s mostly otherwise overlooked “Black pioneers.” In resurrecting this little-known figure, Johnson has returned the favor.

Robin Coste Lewis, poet laureate of LA, considered a chapter from Thoreau called “Former Inhabitants; and Winter Visitors.” She erased much of the existing text, and created a haunting poem about the free black community that once lived at Walden Pond.

In “Another World Lies Beyond,” artist Rosten Woo took as his subject Robert V. Hine (1921-2015), a prominent historian and scholar of utopian communities in California. In reflecting upon the notion of a perfect state, Woo tells a series of interrelated stories through artifacts, a gallery installation, and audio tours in the gardens.

Reflecting on the notion of utopia, I have to admit that for me a fictional ideal world would exclude certain people: people who make noise, people who are hateful, people who don’t get that everything is leaf and act accordingly.

But all over again I realize that to someone else — probably to a whole lot of people — I am that person who doesn’t “get it.” As my friend Father Terry says, “The good news is that God loves you. The bad news is that he loves everyone else, too.” If that is not a picture of the cross, I don’t know what is.

Artist Nina Katchadourian focused her research on monsters depicted in the library’s maps and rare books.

Afterward, I walked through the grounds and looked for her kinetic sculpture “Strange Creature,” which is to be installed in the Chinese Garden.

I didn’t find it, possibly because the Chinese Garden is undergoing a major expansion and all around the edges there is earth-moving equipment, unsightly plastic fencing, and quite a bit of noise, which unfortunately drowns out the peaceful sound of the mini-waterfall and the serenity that might otherwise be invoked by the glassy surface of the reflecting ponds.

But no matter. As science fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin observed, “What kind of utopia can come out of these margins, negations, and obscurities? Who will even recognize it as a utopia? It won’t look the way it ought to.”

I wandered over to the Japanese Garden instead and found a nice bench overlooking a grove of scarlet maples and golden gingkos, resplendent in the afternoon sun.

Let’s face it. The Huntington may be about as close to utopia this side as a person can get.