“I first walked the Hunts Point neighborhood of the Bronx because I was told not to.”

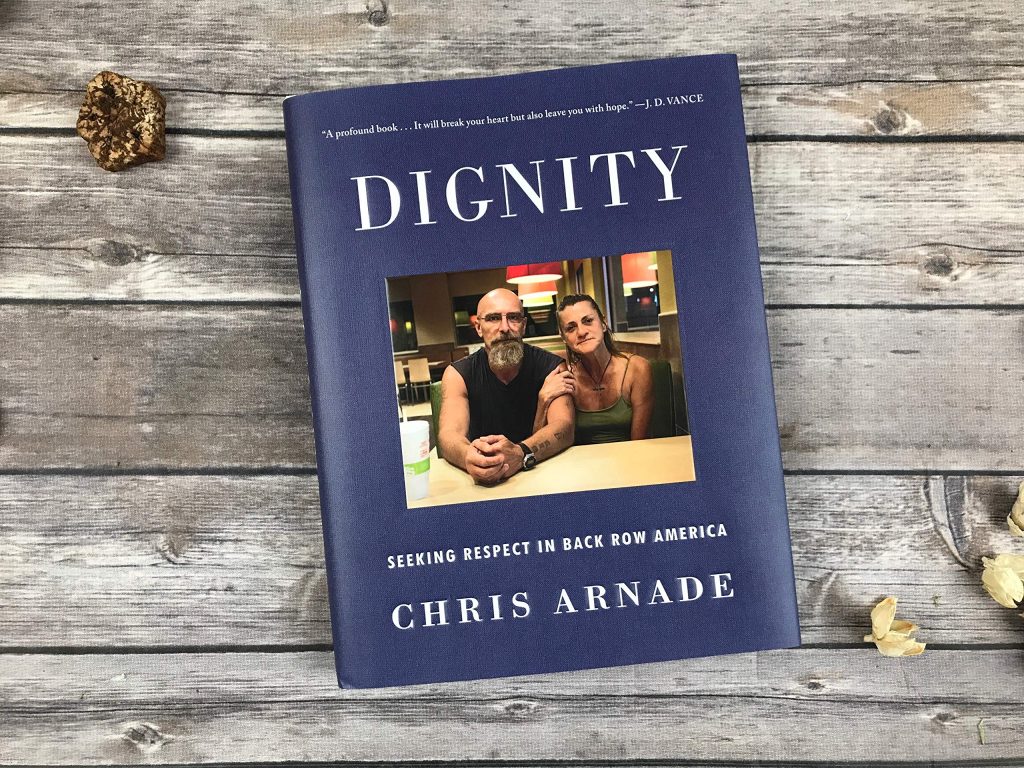

So begins “Dignity: Seeking Respect in Back Row America” (Sentinel, $18), a recently published photo essay collection by Chris Arnade.

A former Wall Street bond trader, Arnade had achieved the American dream when in 2011 he began to get restless. He’d always taken long walks around Manhattan, but now he started venturing into “the less seen parts of New York City, the parts people claimed were unsafe or uninteresting.”

He found his way to Hunts Point, notorious for two things: drugs and prostitutes. Almost entirely black and Latino, roughly 40 percent of its residents live below the poverty line.

He talked to whoever would engage. He brought along his camera and started taking portraits. To his surprise he found community, beauty, creativity, and a sense of place: barbershops, bike shops, pigeon keepers.

He also found the addicts and sex workers, and found as well that they were accepted as part of the community. He befriended Takeesha, who’d been put out on the streets by her mother’s pimp when she was 12 years old. How did she want to be described? asked Arnade. “As who I am,” she replied, without missing a beat, “a prostitute, a mother of six, and a child of God.”

By 2015 he’d quit his job, left Hunts Point, and started taking road trips to towns across America hollowed-out by corporate greed, drug addiction, and white flight. He put 150,000 miles on his car and spent three years sitting beside, talking with, and listening to the stories of the people whom the mostly white elite purport to want to help.

He has no particular “answers.” He has no axe to grind nor agenda to promote.

He doesn’t romanticize the people of “Back Row America.” He gives faces, names, voices, and histories — dignity — to the otherwise unseen and unheard: in Selma, Alabama (where if you’re willing to ruin your hands, you can get a “slave labor” job chipping cement off old bricks for 10 or 20 bucks a day); in Portsmouth, Ohio, where a single, jobless father pushes his kids around town in a shopping cart; in Bakersfield, California, aka “McMeth,” statistically the most back row city in the country.

He discovered that in dying towns all over the country, the local McDonald’s is the new town square. Retired gents in Gary, Indiana, meet for morning coffee and swap stories about the old days. Elderly ladies gather to play bingo. Homeless people can charge their phones, cadge sponge baths, ice and free refills, and sit for hours gossiping, snacking, or napping.

The back row consists of individuals, not types. He finds Trump supporters. He finds those carrying placards reading “American was NEVER great!” In the projects of Cleveland, he talks to a black man, smoking on his stoop, who observes, “You know what I think about Trump? He is so racist, he is past racism, into something we can’t even comprehend.”

Wherever he is, he goes to “services” at the closest church each Sunday morning, and finds himself welcome. He makes this essential point:

“Religion and faith are essential for surviving the streets of the South Bronx. … There are dirty Bibles in crack houses, Korans in abandoned buildings. … Rosaries, crucifixes, and religious icons are worn for protection and good luck. Pages of the Bible are torn out, folded up, and kept in pockets, to be pulled out and fingered nervously or read over in times of stress or held during prayers. ...

“[C]hurches understand the streets, understand everyone is a sinner and everyone fails.”

That the front row’s cultural disdain for religion constitutes a kind of reverse colonialism, in other words, is a notion lost on the elite. A second, related insight has to do with one of the front row’s favored solutions to poverty: just move.

“Telling members of the back row that they should solve their own problems by moving is insulting, no matter who you’re talking to. But it is particularly insulting to African Americans; their entire history in the United States is of forced and coerced movement.”

Everywhere Arnade finds a pride of place, an ache for family, a longing for home. Everywhere, he encounters people staying in blighted areas because they want to take care of their parents, stay close to their friends, raise their kids with the same food, culture, and community with which they were raised.

Arnade understands this impulse to stay put stems not from laziness or fear, but rather a kind of stubborn love that the privileged — whose ties to friends, community, and family tend to be more attenuated, who unthinkingly pull up stakes in pursuit of high-paying jobs, who pride themselves on their “mobility” — can scarcely begin to understand.

In the end, the real glory of “Dignity” may lie here: “The walks, the portraits, the stories I heard, the places they took me, became a process of learning in a different way. Not from textbooks, or statistics, or spreadsheets … but from people.”

That’s the Incarnation in action. “Jesus knew human nature well.” Walking the hills, plains, temple plazas, and city centers of his own time — talking to people, looking into their eyes, reading their hearts: that’s how he learned, too.