I really dislike clichés. Not because they are clichés and a lazy way of transmitting thought, but mostly because of the kernel of truth that resides in them in encapsulated form — which is probably why this form of linguistic sloth has survived as long as it has — and which is kind of irritating.

The truth of the cliché “You don’t realize what you have until you’ve lost it” was writ large on all our foreheads this past Easter week, and it stung. My family and I went from practically living at church from Holy Thursday through Easter Sunday to being shuttered inside our home with our own liturgical needs left to our own devices. I felt like an orphan.

Holy Thursday was problematic, as nobody wanted me to wash their feet. Good Friday gave us the most “bang for our buck” as we recited some beautiful Stations of the Cross that had been devised by St. Pope John Paul II. We then read the passion of the Lord from the Gospel of John and finished the liturgical events with our family tradition of watching “Ben Hur.”

Holy Saturday was another matter altogether. I thought of building a fire outside and lighting candles, but without the presence of an ordained minister of the sacraments and a sense of the sacred, we would have looked more like Druids than practicing Christians, so I scrapped the idea. The splendor and beauty of the Easter vigil just cannot be replicated outside the confines of a church, which brings me to a cliché that has less truth in it than I used to believe.

I have realized that whereas the “church” is more than mere buildings and sacramentals and rituals, the body of Christ is poorer for the lack of them. Noah built an ark, Abraham built an altar, Solomon built a temple, and Jesus turned bread and wine into his body and blood, and he took a real and tangible table and turned it into an altar of sacrifice.

Scripture is filled to the brim with real places, real people, and tangible things that have been bestowed with deeper meaning to feed our souls. We are tactile craving creatures. Jesus obviously knew this in his human nature every time he stubbed a toe or felt a lamb’s wool.

Not hearing the bells return on the Easter vigil, smelling the incense, and gazing upon the art inside our church to help us along in our inner spiritual journey left a void. This current crisis would have been hard enough if it had occurred in the lazy days of summer, post-Lent and pre-Advent. But the fact it hit us square in the face during the holiest time of the liturgical year really does create a sense of communal suffering.

But like all the suffering and sadness that we remember and pray upon during the days leading up to the Lord’s passion, Easter comes just as constantly, only this Easter was like no other.

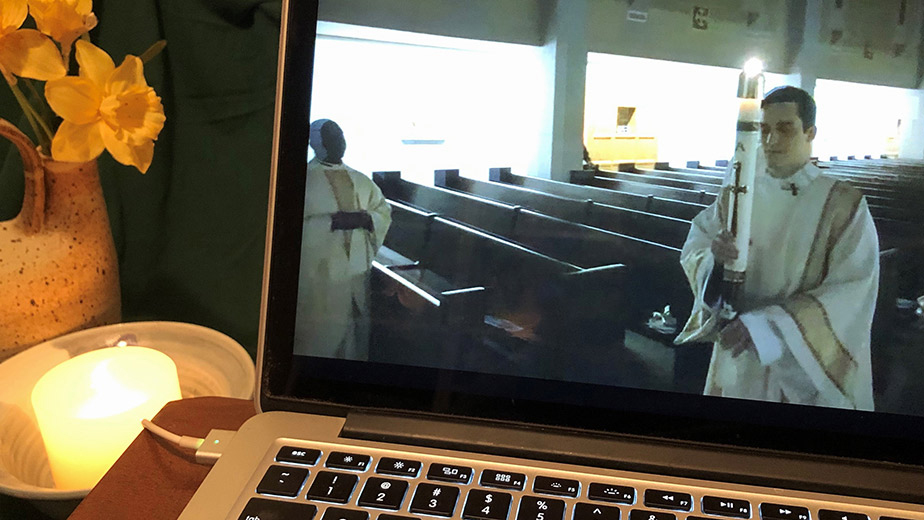

One of the blessings (which are many, if we all take the time to notice) was that my family was able to attend a family Mass. There must have been 40 or so brothers, sisters, nieces, and nephews gathered and our brother, the bishop, celebrated Mass for us. Before anyone calls the Department of Homeland Security, let me assure you the Mass we “attended,” of which our brother presided, was accomplished through the magic of Zoom.

The Mass was supposed to start at 11 a.m. It started closer to 11:15 as we waited for one of my brothers to acquaint himself with 21st-century technology. I realized when setting this up the week before that he might have an issue or two since he never quite acclimated himself to 20th-century technology.

Granted, attending Mass from the dining room table, hunched over a computer screen, was strange, but it was heartwarming to see so many of us in those little boxes on the top of the Zoom screen all gathered together to hear the word on Easter morning. We managed, even with the limitations of doing something sacred online, and stayed focused as our brother celebrated the Mass from his private chapel in his house 200 miles away. And as God as my witness, I did not mute his homily.

As lovely and spiritually uplifting it was to hear Mass from him, a sense of emptiness blanketed me during the consecration. That part of the Mass, that integral element of the whole purpose of the Mass, could not be transmitted to us. We’ll have to wait for 22nd-century technology, I guess.