Death is perplexing. Someone we love is with us in all the rich complexity of his or her personhood one moment; the next moment their body is a lifeless husk. It’s all, ultimately, incomprehensible. And yet, while humans have always wrestled with accepting the awful finality of death, we have had no trouble knowing when it occurs.

Today, however, due to technological advances in critical care, even knowing when death occurs has become a bewildering thing.

As if end-of-life decisions weren’t hard enough, the difficulties increase exponentially when a child is involved, and the natural desires of parents (and their rights) come up hard against the sad reality of death.

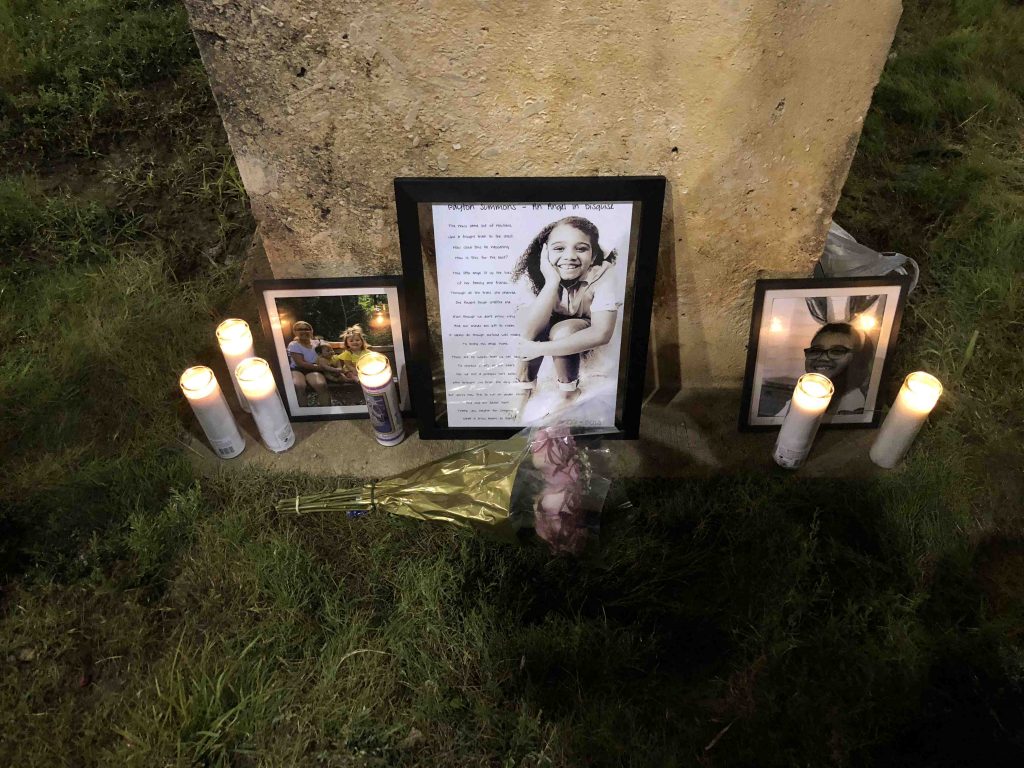

A Texas family recently lost a child after having been caught for several agonizing weeks in both the essential perplexity of death and the difficulty of accepting its occurrence. Payton Summons was a 9-year-old girl who went without warning into cardiac and respiratory arrest, perhaps from a tumor affecting her circulatory system.

Doctors put her on ventilatory and cardiac support, keeping her heart pumping and her lungs moving oxygen. Unfortunately, tests determined that all Payton’s neurological function had ceased. This prompted a declaration of brain death and a plan to remove the machines.

Her family, however, refused to accept the diagnosis. They insisted their little girl was still alive. A court imposed a restraining order against the hospital, giving the family 12 days to find a new facility before the hospital could discontinue mechanical ventilation. Finally, even as it was being supported, Payton’s heart stopped beating.

This Texas case echoes in some ways recent well-known events in England in which parental rights were trampled. There, toddler Alfie Evans was deliberately allowed to die, despite the objections of his parents and an offer of further treatment from a Catholic hospital in Italy.

But the Payton case is substantially different. By all scientifically and ethically accepted measures, Payton, although breathing with assistance, was brain dead. Alfie, by contrast, was reported to be in a “semi-vegetative coma.” He breathed on his own when taken off the ventilator. Alfie was on life-support. Payton was not.

In Catholic hospitals, a deeply reasoned philosophy that cherishes every life until its natural end protects the lives of the unborn, disabled, terminal, and comatose. It’s this ethic that prompted Bambino Gesu hospital in Rome to offer to care for Alfie.

In the case of Payton, however, even a Catholic hospital, informed as it is by an intensely life-affirming ethic, would act no differently than the hospital in Texas.

Catholic end-of-life ethics hold that the competency to determine death belongs to medical science, which uses four neurologic criteria to make the call: unresponsiveness, absence of cerebral reaction to pain, lack of brainstem reflexes, and inability to breathe.

The Church accepts the medical assessment that the patient has died and, from a religious perspective, that means that the soul has flown. Ceasing ventilation and cardiac support is not the cause of death. It’s simply a recognition or acceptance that death has already happened.

Of course, the situation was dreadful for Payton’s family. To be told that Payton was dead, while she was breathing with assistance and looked not so different than nearby ICU patients who are in comas but alive — to be told that it was time to “pull the plug” — was a terrible thing. A terrible and perplexing thing.

Most non-medical people do not understand the definition of brain death, and most people are not ethicists. These are complex issues, shrouded in fear and misunderstanding. The media adds to the confusion with irresponsible reporting about hurried organ donations and a general ignorance about brain death’s diagnosis and meaning.

The media also use imprecise language about patients who were brain dead having had “life support removed, and then died.” It is, of course, impossible for a dead person to die again.

Cook Children’s Medical Center in Fort Worth has a sterling reputation, and diagnosis of brain death, especially of a child, is not given lightly in any hospital. One can be certain that the tests were done and redone, in hopes that some positive sign might be found.

Payton, sadly, had died, and her family should have moved down the hard path of acceptance. Parents have the right, and duty, to demand the best medical care for their sick children, even when hopes of recovery are slim.

But there is no reason to continue intensive care for a person who is no longer with us, no matter how beloved.

Of course, every feeling person that contemplates the reaction of Payton’s family will be sympathetic.

To go from cheerful, humdrum family life to the antiseptic world of the ICU with a catastrophic diagnosis in one short day is enough to bewilder anyone. And, then, to face the perplexity of death — the death of a beloved child — is to enter into tragedy, completely unprepared.

Dr. Grazie Pozo Christie grew up in Guadalajara, Mexico, coming to the U.S. at the age of 11. She has written for USA Today, National Review, Washington Post and the New York Times, and has appeared on CNN, Telemundo, Fox News and EWTN. Her Angelus column, “With Grace,” earned a Catholic Press Association award for “Best Regular Column: Family Life” in 2018. She practices radiology in Miami, Florida, where she lives with her husband and five children.

SPECIAL OFFER! 44 issues of Angelus for just $9.95! Get the finest in Catholic journalism with first-rate analysis of the events and trends shaping the Church and the world, plus the practical advice from the world’s best spiritual writers on prayer and Catholic living, along with great features about Catholic life in Los Angeles. Subscribe now!