The Wende Museum’s Cold War exhibits offer a chance to explore virtue and values

“Wende” (pronounced “venda”) is a German word meaning “turning point” or “change.”

The Wende Museum in Culver City aims by use of the word to describe the “transformative period leading up to and following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.”

Admission is free. The museum is open Wednesday and Thursday for school and university tours only, Friday from 10 a.m. to 9 p.m., and Saturdays and Sundays from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

On offer are art, artifacts and history from the Eastern Bloc.

All is modern, sleek, clean, crisp.

Display boxes lining a side hall include “socialist realism” sculptures, diplomatic gifts, glassware and ceramics, and blocky Cold War radios and telephones that could have come straight from an episode of the ’60s spy-spoof TV series “Get Smart.”

Through August 26, the museum is featuring two principal exhibits.

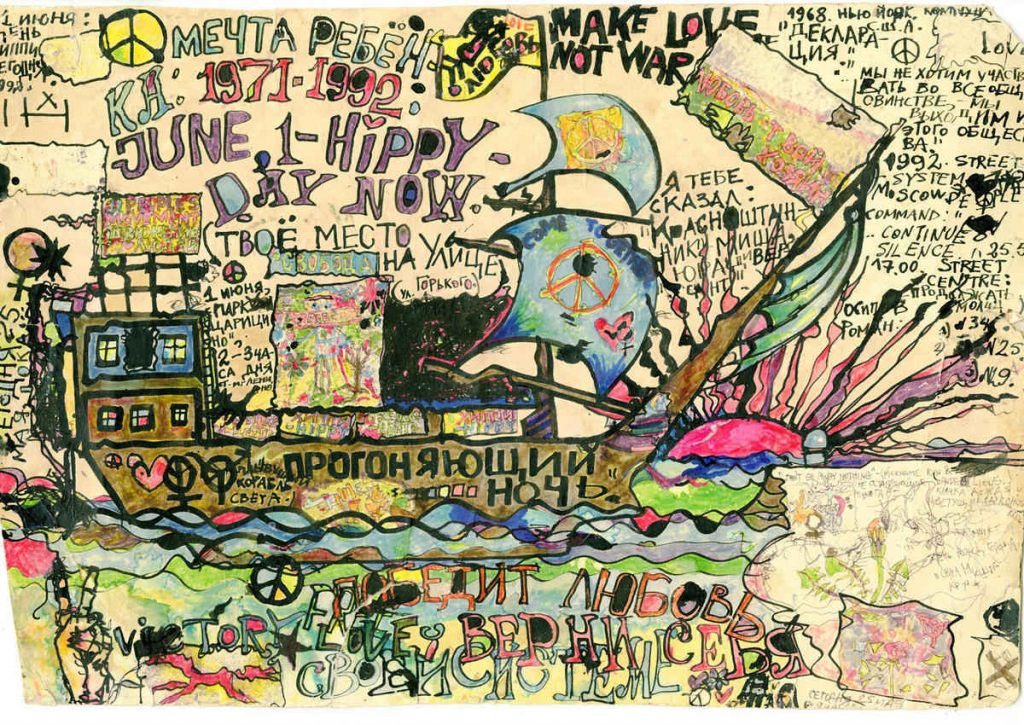

One is entitled “Socialist Flower Power: Soviet Hippie Culture.” Here I learned that, by means of a mysterious movement of the collective unconscious, in the late 1960s teenagers the world over — including those behind the Iron Curtain — spontaneously grew their hair long, donned patchwork bell bottoms, began smoking pot and paid idolatrous homage to the Beatles, the Doors and the Rolling Stones.

The other is called “Promote — Tolerate — Ban: Art and Culture in Cold War Hungary.”

The focus is on the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, which took place roughly between October 23 and November 10. The uprising, against the Marxist-Leninist government, began as a student protest and quickly spread to the general populace.

The contemporary frenzy for violent images, I’m reminded, is nothing new. LIFE magazine ran a photo spread that week, “Patriots Strike Ferocious Blows at a Tyranny,” that featured several Soviet-controlled Hungarian secret police officers in Republic Square being cornered and shot point-blank.

The Hungarian Army, also Soviet-controlled, mostly sided with the rebels. Elections were called for. Communist Premier Imre Nagy himself asked the Communists to leave.

After expressing an initial willingness to negotiate, Soviet tanks returned to Budapest on Nov. 4, 1956, in an effort to crush the revolution.

On November 8, Jonás Kádár established a new government conforming to Soviet ideology. The revolution of 1956 was now styled as a counter-revolution to the Communist Revolution, and its formerly lionized leaders were cast as fascists.

Mass arrests and denunciations followed. Thousands died and 200,000 more became refugees. Nagy was executed on charges of treason in 1958. Public discussion of the uprising was silenced for 30 years.

I had the dizzy feeling I often get when trying to follow the chronology of oppression, uprisings, wars and revolutions: namely, who, at any given time, were the good guys and the bad guys? And have the people who replaced the bad guys done any better?

In 1989, Nagy and other leaders who were executed because of their roles in the 1956 uprising were “rehabilitated” and reburied. “This milestone public event,” notes the commentary, “marked the end of Communist rule, and signaled the subsequent intrusion of Western consumerism together with the values of democracy and freedom.”

Left unexplored is the question of what, precisely, those “values” might be, and how we might best live them out.

In a performance called “Vigil” (1980), for example, a “neo-avant-garde artist” named Tibor Hajas voluntarily entered into a medically induced coma, lay down on the water-flooded floor of an exhibition space and exposed himself to a live current that could have killed him.

Such self-immolation, he held, would lead to the “total freedom at the fragile border between life and death,” as one reviewer put it.

I couldn’t help thinking of Servant of God Father Walter Ciszek, SJ (1904-1984), an individual whose response to the Cold War took a very different form.

A Pennsylvania native, Father Ciszek was ordained in 1937 and developed a passionate call to serve in Communist Russia.

He was arrested there on trumped-up charges of being a Vatican spy, held for five years in solitary confinement, then sentenced to 15 years of hard labor in Siberia.

In the sub-arctic cold, during lunch break, as often as he could, he celebrated a clandestine daily Mass.

In “He Leadeth Me,” he wrote of his fellow believers: “[T]hese men would actually fast all day long and do exhausting physical labor without a bite to eat since dinner the evening before, just to be able to receive the Holy Eucharist — that was how much the Sacrament meant to them in this otherwise God-forsaken place.”

Like Hajas, Father Ciszek stretched his body to its physical and psychological limits.

Like Hajas, he risked his life.

The difference is this: Father Ciszek and his men took their risk with eyes wide open. Under a totalitarian regime, they chose to become more, not less, fully awake, fully alive, fully human.

Father Ciszek survived. He was released in 1955, and in 1963, almost 23 years after his arrest, came home. He spent the rest of his life serving the parishioners he loved.

That total freedom at the fragile border between life and death Hajas so rightly sought is known as the crucifixion.