Sam Maloof, Southern California master woodworker, is known as a pioneer of the post-WWII Studio Craft movement.

Born in 1916 to Lebanese immigrants, Maloof was the seventh of nine children. The family was raised in Chino.

With neither college degree nor formal training, he was known for creating a 2-D design on paper and a 3-D design in his brain.

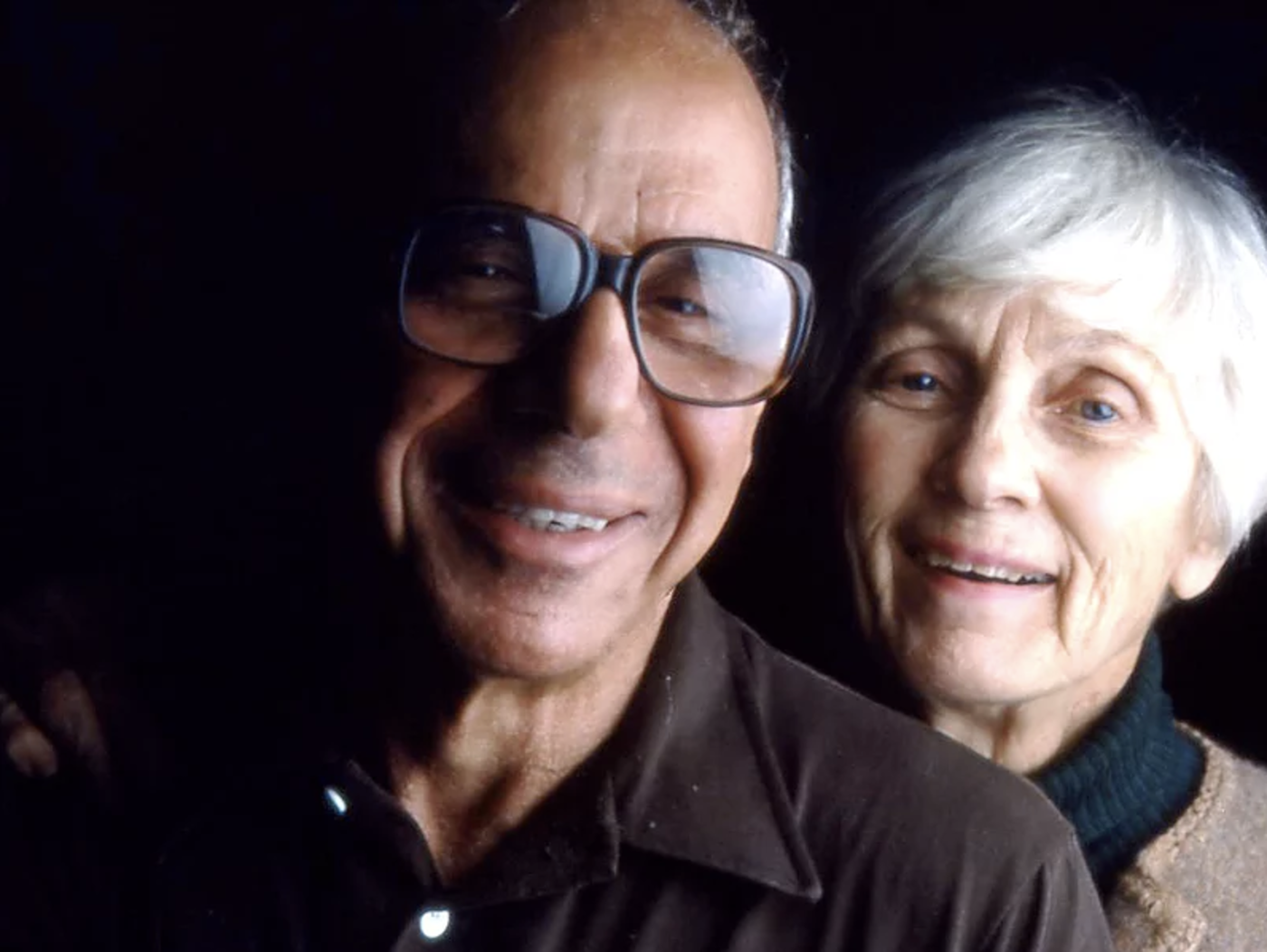

His wife of 50 years, Alfreda, was not only his business manager but the heart and soul of his vocation. “Her faith and love sustained me,” he said. She died in the fall of 1998.

His woodworking vocation was launched when, still single, he rented a bungalow and thought to replace the cheap furniture with pieces of his own that he fashioned from castoff plywood and red oak floorboards salvaged from railroad cars.

He and Alfreda Ward, a teacher and artist, married in 1948. He landed a job with designer Millard Sheets, head of the art department at Scripps College, but the pay was low and the couple started out with next to no money. Five years later they bought several acres, dotted with semi-derelict buildings, in the Alta Loma district of Rancho Cucamonga.

His first work area comprised an old shed and a chicken coop. Unable to afford even a router or band saw, he crafted his early works from the 1950s — a table with “tree branch” legs and a cork top, for example — almost exclusively with a lathe.

Through the years, he added rooms one by one to the house until there were 16 — and a spiral staircase.

His reputation also slowly grew, first throughout Southern California, then the country and finally internationally.

Notoriously gregarious, Maloof invited groups of friends and potential buyers over for dinner. Alfreda would cook, the guests could survey the furniture, and sales would follow.

In 1985, he won a MacArthur genius grant. That same year, the California Creative Arts League declared him a Living Treasure.

Over the course of 45 years, Sam and Alfreda raised children, planted trees, entertained, mentored, harvested vegetables from the garden, constructed studios, sheds, outbuildings, and made of their entire environment a work of art.

In the 1990s, the unthinkable occurred: proposed plans to expand the 210 freeway went straight through the property. After 10 grueling years of negotiations, the State of California declared the compound “historic” and in 2000, provided for the house and woodshop to be moved, piece by piece, three miles to a six-acre former lemon grove at 5131 Carnelian St.

The ordeal was devastating for the entire family, and Alfreda, possibly weakened by stress, died before the move was completed.

Today the Sam and Alfreda Maloof Foundation for Arts and Crafts maintains a gallery, gift shop, not-to-be-missed native garden and working woodshop.

The historic house, now a museum, is open to the public, by tour only, from 12 to 4 p.m. on Thursdays and Saturdays. (Sam built another separate house on the property as his living quarters).

The grounds, redolent of eucalyptus and sage, are lovely. The 10,000-square-foot house of weathered redwood vaguely evokes Japan.

Windows, some tall and narrow, some small and rectangular, are set high in the wall framing views of the mountains, making for a feel both private and outdoorsy.

Counters, window and door trim with expressed dovetail joints, benches, tables, hi-fi consoles, chairs, cradles — all are crafted in satin-smooth, caressable wood in tones of honey, chestnut, amber.

Maloof favored walnut and, for exotics, zircote and rosewood. He used neither nails nor hardware, and liked his beautifully polished joinery to show.

There are Douglas fir crossbeams above the doorways and small stained-glass panels, “soldered” with wood. Each hand-designed door and handle is unique to the house.

The drop-leaf dining room table, made in the 1960s, has matching low-back bench-style settees with padded black leather seats.

The music stand and armless folding chair Maloof designed in 1969 and 1972, respectively, for violist Jan Hlinka, principal violist of the LA Philharmonic, are here. Hlinka had one request: don’t make this chair for anyone else until I die.

A lover of textiles, Alfreda laid out Zapotec and Navajo rugs on the warm brick or wood floors. Also per Alfreda, the house was heated through the mid-1990s exclusively via woodstove.

The Maloofs also collected paintings, sculpture and, especially, ceramics, all on prodigious display.

But Maloof is perhaps best known for his rocking chairs: simple, structural, elegant. For more than 40 years, he continued to refine the style. His later chairs featured sensuous curves, as if accentuating the contours and beauty of the human body.

In the video that introduces the tour, Maloof is in his mid-80s, has just bought a Porsche convertible, and still works 10-12 hours a day. “I couldn’t put my name to a piece of furniture my hand hadn’t touched.”

He died at 93, in the home he loved. “Where am I going?” he reputedly asked on his deathbed.

A musician, however, may have had the very last word. Ray Charles, the blind singer-songwriter, once ran his hands over a Maloof piece, legend has it, and declared that it had soul.