It wasn’t so much the look of poverty as she saw it a century ago in the teeming tenements of New York that outraged Dorothy Day as it was the smell. Many years later in her autobiography “The Long Loneliness,” she described it like this:

“The smell from the tenements, coming up from basements and areaways, from dank halls, horrified me. It is a smell like no other in the world and one never can become accustomed to it. I have lived with these smells now for many years, but they will always and ever affront me. I shall never cease to be indignant over the conditions which gave rise to them. ... It is not the smell of life, but the smell of the grave.”

Then Day added something startling: “As I walked these streets back in 1917, I wanted to go and live among these surroundings; in some mysterious way I felt that I would never be freed from this burden of loneliness and sorrow unless I did.”

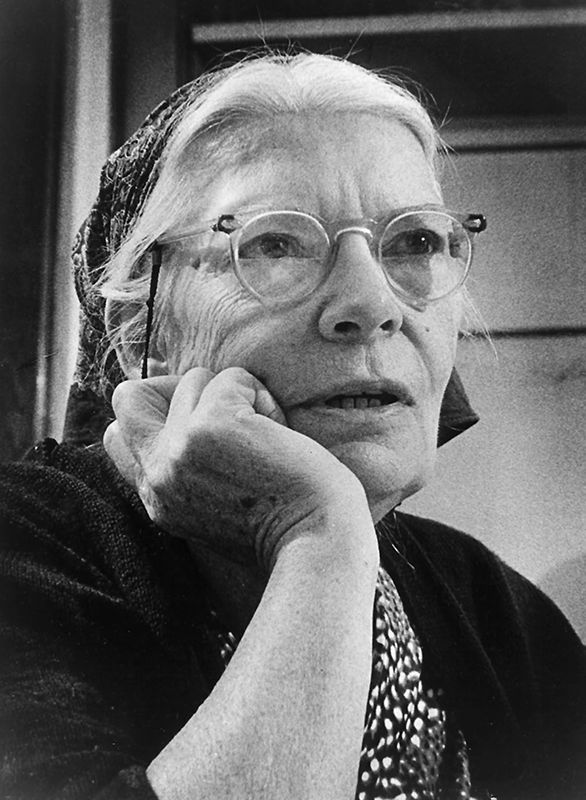

The future cofounder of the Catholic Worker Movement, whose cause for canonization as a saint has reached the stage of a canonical inquiry into her life in the Archdiocese of New York, arrived there in 1916 after dropping out of the University of Illinois. Only 18, she already had a burning desire to help the poor as a crusading journalist.

The New York Call was a good place for her to start. As the newspaper of the American Socialist Party, the Call was as open to advocacy as it was to reporting, and this cub reporter fit in from the start. Between November 1916 and April 1917 the Call carried 36 bylined pieces by Day, along with an unknown number anonymous articles by her as well.

Now the bylined items have been reprinted with an informative commentary in a volume titled “An Eye For Others: Dorothy Day, Journalist: 1916-1917” (Washington, Clemency Press). These pieces shed light on a largely ignored formative period in Day’s long, luminous life, showing her as a young woman who, in the words of compiler and commentator Tom McDonough, is “sarcastic, humorous, energetic and sardonic” — and never less than deeply committed.

This is apprentice work, yet with memorable flashes of passion and power. As in this, dated Nov. 30, 1916:

“In a two-room flat on 11th Street, a man of 48 lies wheezing and moaning all day. He cannot eat anything, because there is something the matter with his stomach and with his lungs, and every once in a while blood pours out of his nose and mouth. He could drink milk, but milk is now 10 cents a quart. And the only money that is coming into the house is the $5 a week that his wife earns in a restaurant as helper in the kitchen. …

“So, when the rent is to be paid, and when the doctor prescribes medicine for the sick man, the family must go hungry. They need coal now and some food. Today is Thanksgiving.”

Other sketches concern things like an angry picket line, a grim night court, an unsought wee hours cab ride with a lascivious taxi driver and other glimpses of the big city’s underside.

Day’s religious conversion then lay years in the future, but the makings of a woman of extraordinary courage and compassion are already visible in these early writings. Some saints are formed in castles, others in convents; Day’s houses of formation, it appears, were the fetid tenements of New York.

Russell Shaw, a contributing editor to Our Sunday Visitor, writes from Washington, D.C.