We can make time, waste time, call time, find time, lose time, and sometimes feel like time is on our side. In reality, time is not on anybody’s side. And as scientific endeavors in the realm of quantum physics keep progressing, the arguments are that stipulating time is strictly a human invention.

The Church has played her own role in helping us get a handle on time. Pope St. Gregory the Great helped put some order in our observations of celestial bodies with the same calendar we use today. It gives us chronological parameters to our finite human bodies as they travel through what appears to be time until we get to the point where we stop traveling altogether and time no longer matters.

In what might be construed as an example of having too much time on my hands, I read an article about time in Scientific American. I had to read the article three times before I was only mildly perplexed about all the theories whirling around about the concept of time.

According to the article, a lot of brainy people have tried to break down the concept of the passage of events with various degrees of success — and various degrees of successfully imparting what they discovered to untrained and parochial brains like mine.

On the fifth or sixth go around with this article —I’m not sure because I lost track of the time — a quote from a French philosopher named Maurice Merleau-Ponty provided an epiphany for me.

He argued that time itself does not really flow, and that its apparent stream is a product of our “surreptitiously putting into the river a witness of its course.”

This revelation seemed timely indeed, as it came on the heels of watching and reading all about the Eucharistic Congress in Indianapolis. Like so many things related to our faith, the more science discovers, the stronger the foundations of our faith become. And like faith, science develops over time, bringing a deeper understanding of the truth.

The Eucharistic Congress is over. Those who gathered in Indianapolis last month have returned home to the four corners of the country, and are going about their daily lives. But I am sure the vast majority of them will continue going to Mass — and by doing so, find themselves bending time in a way no science fiction writer ever imagined.

Scientific inquiries into the nature of time dovetail so seamlessly into the Church’s teaching on what the Eucharist is. Just as our minds should be astounded by the concept of time or timelessness, so too should our souls be stirred by Christ’s ultimate gift to his followers. First modeled for us at the Last Supper and coursing through our concept of time ever since, the Eucharist exists in all its glory, whether among 60,000 gathered in a sports stadium or where two or more are gathered in the humblest chapel tabernacle anywhere in the world.

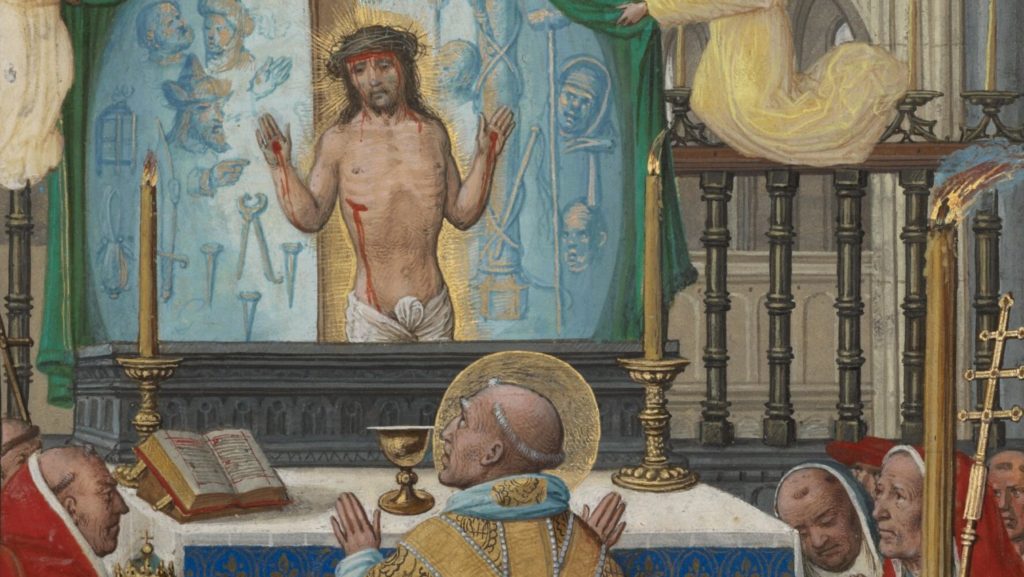

Every Mass is a re-presentation of Christ crucified, Christ resurrected, Christ present. We are not recalling something from the past, we are not looking to the future. Since God is not bound by time, neither is the Mass, in whatever form it takes.

At every Mass, those present are brought to Golgotha, where the one and only Passion takes place. The liturgical rubrics are the conveyance to this moment, and we join the angels and the few disciples who were there at the foot of the cross.

How can this be? I do not know. I do not know how the sun never runs out of hydrogen even though it has been burning several hundred million tons of it every minute for billions of years.

That sounds impossible, but it is true. I know the Eucharist is the body, blood, soul, and divinity of Jesus. That sounds impossible too. Certainly, a lot of people in the sixth chapter of John’s Gospel thought so. But Jesus was adamant, and his word is good enough for me.

There is a call to “follow the science” favored by many among the growing number of nonbelievers in our culture. I concur. But I would caution those who pronounce that phrase as an “answer” to the nonmaterial to be wary of what you wish for. For as we continue to follow the sometimes circuitous path of science, the “super” in supernatural racks more and more into focus.

And as the Eucharistic Revival showed this year, and will be shown once again next year when a nationwide Eucharistic procession completes its journey here in Los Angeles, God’s salvation is timeless, and so is the Eucharist and the souls that are drawn to it.