If you are still looking for a good New Year’s resolution this January, I’d suggest spending some time with a few saints … 365, to be exact. If your first thought is, “That sounds boring,” then you don’t know saints.

For the last few years, I’ve been reading a short life of a saint each day of the year. It has been a practice that has had me traversing all the centuries of the Church’s history, an adventure that has been almost always inspiring and occasionally shocking.

Of course, we all know the stories of a few saints — St. Patrick and St. Nicholas, perhaps — though much of what we think we know may be more legend and pious tradition than fact. Knowing only the holy card version is a disservice to the very real flesh and blood women and men who preceded us and from whom we can learn so much.

The real stories of the saints are a reminder that history is always messy. The past is no over-simplified golden age disconnected from what we are experiencing today.

At a time when the Church challenges our own rulers on abortion, immigration, and the death penalty, there are endless examples of the saints resisting the authorities. Take St. Ambrose. In the 4th century, both Church and state were divided by the Arian heresy, pitting would-be emperors against one another. St. Ambrose was an esteemed defender of orthodoxy, but also a beloved leader negotiating a maelstrom of competing interests. At one point, his people had to fill a church to protect him from being seized by imperial troops. Exemplifying grace under fire, he taught the people hymns as they outwaited the soldiers.

Church-state relations figure prominently in many stories. The Church calendar pays tribute to the many brave priests and laity in Great Britain who were killed for refusing to renounce their Catholicism during the reigns of Queen Elizabeth and King James. The tortures were cruel and executions drawn out and painful.

Saints often goaded the consciences of the powerful. St. Peter Claver was a Spanish Jesuit in the 17th century who went to Colombia, where he ministered to the Africans that Spanish slave traders were bringing at the rate of 10,000 a year. St. Peter called himself Slave of the Africans and tried to care for those who survived the brutal conditions on the boats.

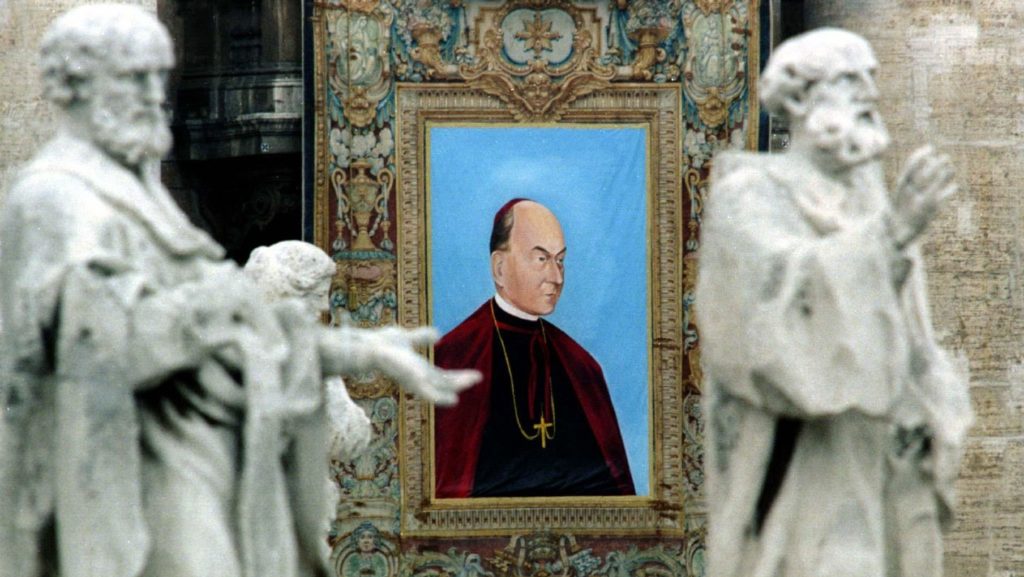

In the 20th century, many saints were martyred by fascists or Communists. Blessed Vilmos Apor, who lived in the first half of the 20th century, was born in Romania. He was a bishop who understood early the evil of Nazi ideology. “One cannot tolerate antisemitism,” he wrote to a fellow bishop. “What Jews are undergoing is genocide.” When Russia occupied Romania after World War II, he sought to help the many refugees. On Good Friday, 1945, he was defending a young woman from harassment by drunken soldiers, and they shot him.

Blessed Maria Stella Mardosewicz and 10 other religious women in Poland were executed by the Nazis after they sought to save the life of a priest. Ukraine’s many martyrs, remembered on March 5, were killed over a period of 38 years by both Nazis and Communists.

In the saints’ lives we see examples of strong women who were not afraid to speak truth to power. Take, for example, Blessed Mary MacKillop, who lived in 19th-century Australia. Her commitment to education, care for the sick, the homeless, and unmarried women at times meant she locked horns with Church authorities. She is “an obstinate and ambitious woman,” one bishop said of her. She “battled lifelong opposition to her work,” a biographer wrote, and was even excommunicated for a short while.

Our own St. Katherine Drexel, who grew up in Philadelphia into a family of bankers, lived from 1858 to 1955. Despite her wealth, she was tremendously dedicated from an early age to the care for Native Americans and, later, African Americans. Inheriting her family’s great wealth, she traveled throughout the country, using her money to start schools, missions, and orphanages, including what was to become Xavier University in New Orleans.

What characterized many saints was their charity and concern for the poor. What we now might call the social Gospel was alive and well from the earliest days of the Church. Unlike the rich young man in the Gospel, many saints were willing to sell everything and even to beg in order to support those in need.

In our cynical and depleted age, 2025 may be a good year to be inspired daily by men and women who met the challenges of their age and bore witness to the faith.

Where to start? Two resources I use are “Butler’s Saint for the Day,” by Paul Burns (Liturgical Press, $34.95) and “Voices of the Saints” by Bert Ghezzi (Loyola Press, $19.95). Most recently Bishop Robert Barron’s Word on Fire Press has published “Voices of the Saints: A 365-Day Journey” ($34.95).