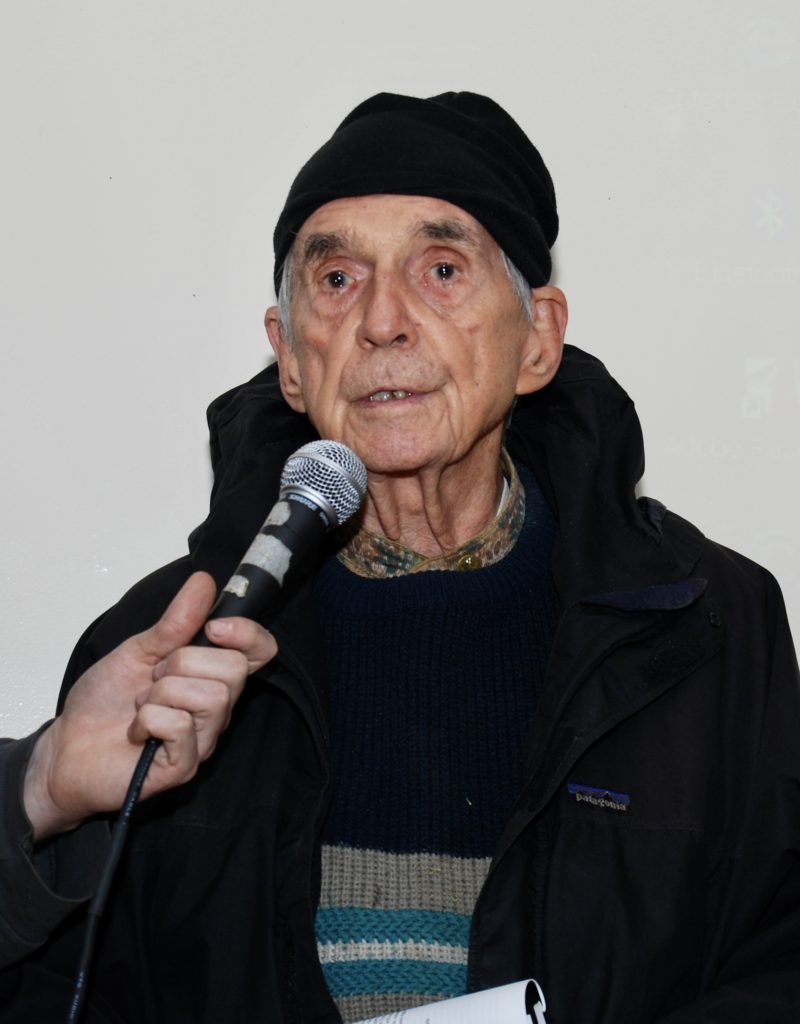

After his first arrest, the peace activist Father Daniel Berrigan, SJ, went into hiding. After four months, he was captured, but during those months underground, although a threat to no one, he was put on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list. There’s an irony here that did not go unnoticed. Someone put up a poster of him with this caption: “Wanted – Notorious consecrator of bread and wine. Disturber of wars and felonious paper burner! The fugitive has been known to carry the New Testament and should be approached with extreme caution. Disarmed and dangerous.”

Disarmed and dangerous! Corny as that may sound, it expresses the real threat to injustice, violence, and war. Disarmament is dangerous. Someone who is genuinely unarmed is ultimately the one who poses the greatest danger to disorder, immorality, and violence. Violence can withstand violence, but it can be brought down by nonviolence. Here are some examples.

In our own generation, we have the example of Father Christian de Cherge, OCSO, one of the seven Cistercian monks who were kidnapped and later killed by Islamist extremists in Algeria in 1996. His journey, and that of the other monks who died with him, is chronicled in a number of books (including some of his own letters and diaries) and in the awarding-winning film, “Of Gods and Men.”

Living within a small community of nine monks in a remote Muslim village in Northern Algeria, Father de Cherge and his community were much loved by that Muslim community and, being French citizens and enjoying the protection of that citizenship, their presence constituted a certain protection for the villagers against Islamic terrorists. Alas, the situation was not to last.

On Christmas Eve, 1995, they received a first visit from the terrorists with the clear warning that they had best leave before they would become its victims. Both the French and the Algerian governments offered them armed protection.

Father de Cherge, acting alone at first, against the majority voice in his own community, categorically refused armed protection. Instead, his prayer became this: “In face of this violence, disarm us, Lord.” His response to the threat was complete disarmament. Eventually, his entire community joined him in that stance.

Six months later they were kidnapped and killed, but the triumph was theirs. Their witness of fidelity was the singular most powerful gift they could have given to the poor and vulnerable villagers whom they sought to protect, and their moral witness to the world will nurture generations to come, long after this particular genre of terrorism has had its day. Father de Cherge and his community were disarmed and dangerous.

There are innumerable similar examples of other persons who were disarmed and dangerous. Rosa Parks, disarmed and seemingly powerless against the racist laws at the time, was one of the pivotal figures in ending racial segregation in the USA, as was Martin Luther King Jr.

The list of dangerous unarmed persons is endless: Mahatma Gandhi, Father Thomas Merton, Dorothy Day, Desmond Tutu, Archbishop Óscar Romero, Franz Jägerstätter, Sister Dorothy Stang, Father Daniel Berrigan, SJ, Elizabeth McAlister, Father Michael Rodrigo, OMI, Father Stan Rother, and Jim Wallis, among others. Not least, of course, Jesus.

Jesus was disarmed and so dangerous that the authorities of his time found it necessary to kill him. His complete nonviolence constituted the ultimate threat to their established order. Notice how both the civil and religious authorities at the time did not so much fear an armed murderer as they feared an unarmed Jesus.

“Release for us, Barabbas! We prefer to deal with an armed murderer than with an unarmed man professing non-violence and telling people to turn the other cheek! Give them credit for being astute.” Unconsciously, they recognized the real threat, someone who is unarmed, nonviolent, and turning the other cheek.

However, turning the other cheek must be properly understood. It is not a passive, submissive thing. The opposite. In giving this counsel, Jesus specifies that it be the right cheek. Why this seemingly odd specification? Because he is referring to a culturally-sanctioned practice at the time where a superior could ritually slap an inferior on the cheek with the intention not so much of inflicting physical pain as to let the other person know his or her place — “I am your superior, know your place!”

The slap was administered with the back of the right hand, facing the other person, and thus would land on the other person’s right cheek. Now, in that posture, its true violence would remain mostly hidden because it would look clean, aesthetic, and as something culturally accepted.

However, if one were to turn the other cheek, the left one, the violence would be exposed. How? First, because now the slap would land awkwardly and look violent; second, the person receiving it would be sending a clear signal. The change in posture would not only expose the violence but it would also be saying, “You can still slap me, but not as a superior to an inferior; the old order is over.”

Disarmed and dangerous. To carry no weapon except moral integrity is the ultimate threat to all that is not right.