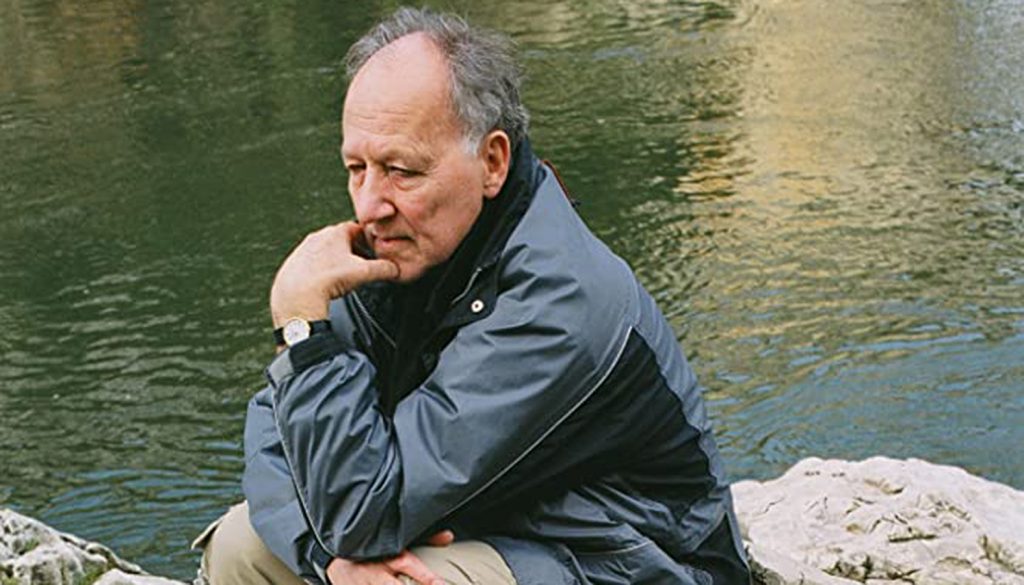

The German filmmaker Werner Herzog aims high. “I seek certain utopian things,” he says, “space for human honour and respect, landscapes not yet offended, planets that do not exist.”

I’ve written here of “Land of Silence and Darkness,” the 1971 documentary on the deaf-blind many consider his finest film.

He’s perhaps best known for “Aguirre: The Wrath of God” and “Grizzly Man.” You can stream some of Herzog’s other work on YouTube, including “How Much Wood Would a Woodchuck Chuck,” 1976 (World Livestock Auctioneer Championship), “Gesualdo: Death for Five Voices,” 1995 (Renaissance prince and sacred music composer who stabbed his wife and her lover to death), and “Herdsmen of the Sun,” 1989 (includes an unforgettable clip of Saharan nomadic Wodaabe tribesmen performing their mating dance to the strains of Gounod’s “Ave Maria”).

Herzog was raised in a remote German village in the Bavarian Mountains. His parents were divorced and his father was physically and emotionally absent.

“I was very much alone in my early childhood,” he has said. “I was quite silent and wouldn’t speak for days. … I was very dangerous, my character was peculiar; it’s almost as if I had rabies.”

At 15, he had a profound religious experience and, attracted by the “ritual, the unbroken tradition” in the Church, converted to Catholicism. He lapsed within a couple of years, citing “dogmas” and “church hierarchy.”

But in his single-minded devotion to “ecstatic truth” — and to the work he was born for — he remains Catholic down to the ground.

He knew from a very young age that film was his destiny and vocation. He worked as a welder to finance his first three short features and became his own producer at the age of 17.

He claims to have been bitten by rats in a North African jail. He once walked, so he says, from Munich to Paris in order to beg the iconic film historian Lotte Eisner, ill at the time, not to die (she didn’t).

To believe that his walking can prevent someone else’s death is not, he insists, megalomania. “Ultimately, [such acts] are great gestures. They are gestures of the soul, and they give meaning to my existence.”

He famously threatened to shoot the late German actor Klaus Kinski dead on the set of the 1982 West German epic adventure-drama “Fitzcarraldo” if he quit before the film was finished.

One senses the two found their match in each other, and Herzog later made a documentary about their fruitful but tortured collaboration called “My Best Fiend” (1999). “We had a great love, a great bond, but both of us planned to murder each other. Klaus was one of the greatest actors of the century, but he was also a monster and a great pestilence. Every single day I had to think of new ways of domesticating the beast.”

Herzog has strong opinions. He believes chickens to be the stupidest creatures on earth, perhaps evil. He despises the theater, museums, and yoga.

He has little use for film school or film theory. “Film is not analysis, it is the agitation of the mind; cinema comes from the country fair and the circus, not from art and academicism.”

He divides his time between Munich and LA, calling the latter a place of great substance and creative energy. “Things get done here.”

Still, “our grandchildren will blame us for not having tossed hand grenades into TV stations because of commercials. Television kills our imagination.”

For a culture as purportedly as advanced as ours, “to be without images that are adequate to it is as serious a defect as being without memory.”

He sees it as his sacred honor to create the images himself, by whatever means necessary. He thus unabashedly admits to staging scenes and writing dialogue for what purport to be documentaries.

“Bells from the Deep,” for example, his 1993 exploration of Russian mysticism, ostensibly depicts believers who lie down on a frozen lake and peer beneath the ice looking for the lost city of Kitezh.

“As there were no pilgrims around I hired two drunks from the next town and put them on the ice. One of them has his face right on the ice and looks like he is in very deep meditation. The accountant’s truth: he was completely drunk and fell asleep, and we had to wake him at the end of the take.”

As Herzog maintains, “I think the scene explains the fate and soul of Russia more than anything else.” Besides, are not drunks in their way, looking for a lost city, too?

When challenged in a recent New York Times interview, he replied: “I’ll make it very simple. My witness is Michelangelo, who did the statue of the Pietà. When you look at Jesus taken down from the cross, it’s the tormented face of a 33-year-old man. You look at the face of his mother: His mother is 17. So let me ask: Did Michelangelo give us fake news? Defraud us? Lie to us? I’m doing exactly the same. You have to know the context in which you become inventive.”