ROME — In a deeply polarized environment, the Democratic Party nominates a veteran Roman Catholic senator to challenge a Republican incumbent who makes much of his religious support, especially from evangelicals and conservative Catholics.

Because the Democrat is both Catholic and pro-choice, bishops are faced with a hard choice of how to register disapproval without seeming partisan, while the wider American Catholic world engages in a nasty to-and-fro about whether such a candidate can ever be supported.

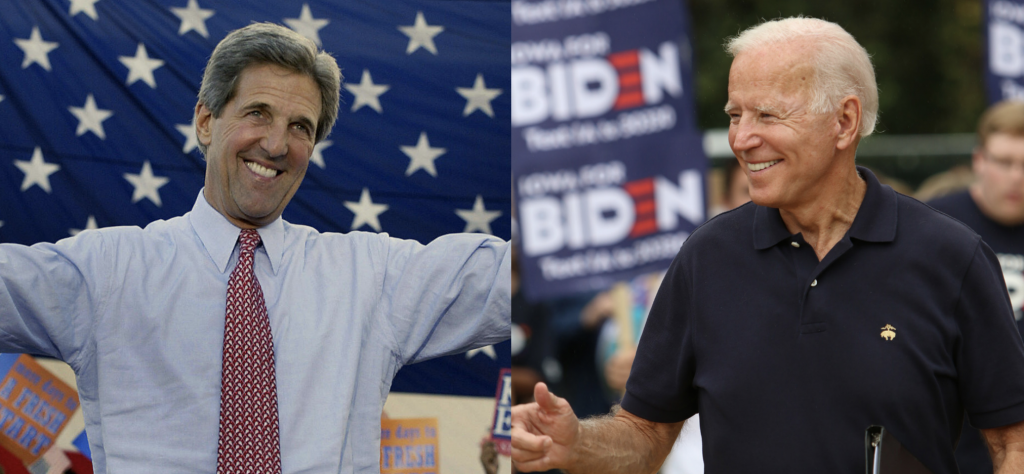

That could easily be a description of this year’s Trump vs. Biden race, but it actually refers to the situation 16 years ago, when the Democrats nominated Sen. John Kerry of New Hampshire to take on President George W. Bush.

Looking back at that 2004 campaign and its repercussions for the Church offers a reminder both of how much has changed since then, and also how much hasn’t.

By 2004, an entire generation of American bishops were shaped by the ethos of St. Pope John Paul II’s papacy, which included a robust commitment to the pro-life cause.

As it became clear in spring 2004 that Kerry would be the Democratic nominee, a few American bishops began announcing — sometimes on their own, sometimes in media interviews — that should Kerry present himself for Communion, he would be refused.

They included Archbishop Raymond Burke of St. Louis, who would go on to serve in the Vatican and then emerge as one of the “dubia” cardinals questioning Pope Francis.

Critics of denying Communion said it politicized the Eucharist and risked making the bishops look partisan, which would simply make it harder to build consensus around the pro-life position. When the U.S. bishops gathered for their spring meeting in Denver, it was clear the controversy would loom large.

In advance of the meeting, then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, then the Vatican’s doctrinal czar, wrote a letter to the head of an ad hoc committee the bishops had created to ponder the problem: Cardinal Theodore McCarrick of Washington, D.C., who would go on to be expelled from both the College of Cardinals and the priesthood over charges of sexual misconduct and abuse.

McCarrick didn’t present the text of Cardinal Ratzinger’s letter to the bishops, leaving the impression that while Cardinal Ratzinger had expressed cautions and general principles, he had not directly insisted on denying Communion. In the end, the conference couldn’t reach general agreement and left it in the hands of individual bishops.

One month later, veteran Italian journalist Sandro Magister published the full text of the Cardinal Ratzinger letter, the heart of which was that if private efforts to dissuade Catholic politicians from positions contrary to Church teaching fail, and “the person in question, with obstinate persistence, still presents himself to receive the holy Eucharist, the minister of holy Communion must refuse to distribute it.”

There were accusations that McCarrick had deliberately misrepresented Cardinal Ratzinger, though Cardinal Ratzinger later wrote a letter applauding the document the bishops adopted at Denver, which McCarrick touted as a sort of exoneration.

In the end, there was no general policy among the U.S. bishops and both sides in the debate claimed victory.

Sixteen years later, what hasn’t changed is that there still is no uniform standard about when to deny Communion, meaning a bishop or priest genuinely wondering what to do doesn’t have crystal-clear guidance.

The Cardinal Ratzinger letter was never rescinded, but a letter from a Vatican official to the head of an ad hoc committee in one country’s bishops’ conference isn’t terribly far up the food chain in terms of teaching authority, and it’s not clear the same position would be expressed under this papacy anyway.

What also seems the same is the dilemma facing ordinary American Catholics, some of whom feel as disenfranchised in 2020 as they did in 2004.

In 2004, a vote for Kerry bolstered the pro-choice position, while a vote for Bush felt like an endorsement of the war in Iraq; now, a vote for Biden still strengthens the pro-choice camp and arguably rewards the Democrats for driving the pro-life camp out of the party, while a vote for Trump is, well, a vote for Trump.

One thing different now is that the cast of characters from 2004 won’t drive the discussion. As Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, and at 93, the former Cardinal Ratzinger won’t be involved; Archbishop Burke no longer leads an American diocese or heads the Vatican’s supreme court; and McCarrick’s now isolated in a Capuchin friary in Western Kansas, ending his career in disgrace.

The bigger difference, however, is the pope under whom the debate is unfolding.

Pope Francis is a man of dialogue rather than open confrontation, especially with politicians, and most of his bishops’ appointments are cut from the same cloth.

Further, the precedent set by the 2016 document “Amoris Laetitia” (“The Joy of Love”), that someone objectively in violation of Church norms may nevertheless receive Communion after a careful process of discernment, suggests caution about definitive declarations in any particular person’s case.

There’s also a much broader sense under Pope Francis of what counts as a “pro-life” issue. While the pope is sternly anti-abortion, calling it a “horrendous crime” and a “very grave sin” in 2016, he’s equally emphatic that respect for human dignity and life must also include the environment, migrants and refugees, war and peace, and other matters.

If bishops are going to start denying politicians Communion for not being “pro-life” enough, therefore, it’s hard to know where it would stop.

As a result, it seems unlikely the stage is quite set for a repeat of 2004. We may be spared a fracas among the American shepherds, in other words — but alas, that still won’t do much to help their flock figure out what to do themselves.