When Woody Allen was a standup comedian, he had a joke that always stayed with me. He said he had taken a speed-reading course, immensely popular in the early 1960s when this joke was conceived. Upon completion of the course, Allen told his audience the first book he tackled using this new speed-reading skill was “War and Peace.” After a perfectly timed pause, he concluded: “It’s a novel … about Russia.”

Words matter. “War and Peace” has 580,000 of them. Only about 25 years after Tolstoy’s masterpiece, American writer Stephen Crane wrote his great “war” novel, “The Red Badge of Courage.” It has 55,000 words. Both novels, in their unique way, speak to universal truths, even though you would be hard-pressed to find two more dissimilar books. And people are still trying to figure out exactly what the 209,117 words of “Moby Dick” actually mean.

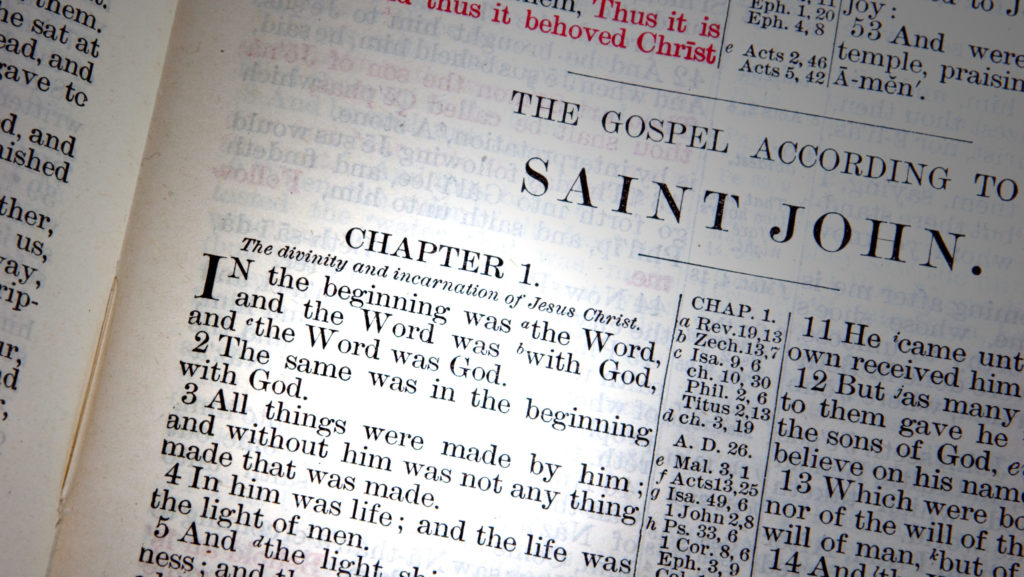

When it comes to holy Scripture, we have nearly 800,000 words to contend with, and if words were not important, the Gospel of John would not begin with: “In the beginning was the word.”

I did not take the time to calculate how many sentences all those holy words formed, but it is easy to see how we can get into the weeds, especially if we view the Bible as a solitary book rather than a collection of books with different historical, literary, and biographical content, written for different people during different epochs. In God’s time and God’s playbook, all of these books coalesce into a single body, in the same way as the Church is both many and one. But the mortar for the structure always was and always will be words.

Unfortunately, since the advent of the Reformation, words within the confines of holy Scripture have been reinterpreted and even altered to serve a specific agenda, rather than agendas formulated from authoritative words. This has resulted in a cottage industry of “new” revelations that heretofore the Church had somehow missed. And just as anyone with a Best Buy microphone and cellphone can be podcasting, just about anyone can become a biblical scholar.

This has all led to departures of orthodoxy ranging from “prosperity gospels” where God is some kind of spiritual Shark Tank benefactor, to taking the Book of Revelations and finding instructions on how to be counted among a specific number of chosen people who will be whisked away to safety when the forces of good and evil go medieval on each other during the end times.

But, praise God, the Church has been chiseling order out of confusion since the Council of Nicaea. The proliferation of personal interpretations of Scripture has not brought unity, and the division that it has sown is the proof of its error. Just as we rely on faith and reason in our spiritual sojourns, through the Church we rely on Scripture and her time-tested interpretation of said Scripture.

This can be heady stuff, but there is a remarkably straightforward way of explaining how imperative it is not to rely on our interpretations. It is an old grammatical exercise consisting of a simple sentence of only seven words. “I never said she stole my money.” It certainly seems simple enough, until we emphasize one word over all the others. Try the sentence like this: “I never said she stole my money.” That is something altogether different than if you said it this way: “I never said she stole my money.” You can play the home version of this game by emphasizing a different word in this sentence every time you read it and discover how many interpretations one can construct.

Jesus knew his creatures well, and even though he said things the evangelists admitted the apostles did not fully comprehend when they first heard them, he was also adept at being explicitly clear by using less, not more, words. Unambiguous simple sentence gems such as “It is finished” and “Feed my sheep” permeate the four Gospels.

But the ultimate gift Jesus bestowed on us came in another simple sentence with the same number of words as those found in the grammatical exercise. No matter what word you emphasize in this quote from Scripture, the meaning remains the same — and remains life-changing: “Take and eat; this is my body.”

Words to live by.