Public shaming, scolding, and snitching aren’t punishable by law, but everyone knows betraying a friend is a dastardly moral crime.

In Dante’s “The Divine Comedy,” the final, ninth circle of hell is reserved for those who betray, in descending order: their family, their country, their guests, and their masters, mentors, and friends.

The worst of the worst is to condemn a friend to death for money.

Thus, the last tier of the lowest circle is where Judas Iscariot resides, mired in icy slush, eternally consumed by Satan himself.

As Catholics, we’re called by moral law never to betray our loyalty to Christ and his Church — and it would seem, by extension, to our friends.

In the “Catechism of the Catholic Church,” at Section 1735, however, it carves out implicit exceptions for, say, torture or threats of death: “Imputability and responsibility for an action can be diminished or even nullified by ignorance, inadvertence, duress, fear, habit, inordinate attachments, and other psychological or social factors.”

Heroic souls who hold out regardless do exist.

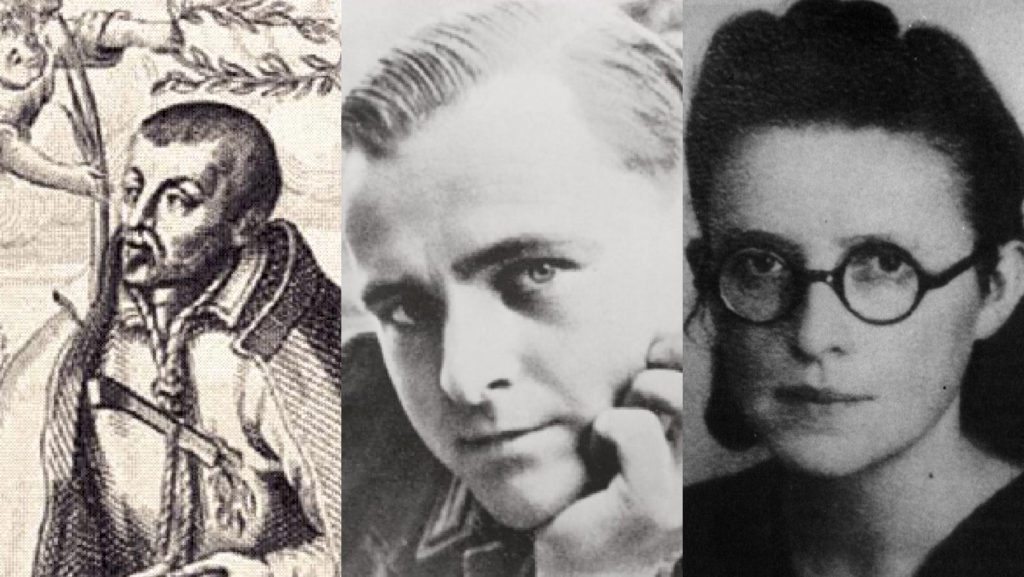

St. Robert Southwell (1561-1595), a Jesuit priest, for example, was canonized in 1970 as one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales.

At war with Catholic Spain in 1585, Protestant England passed the Act against Seminary Priests and Jesuits, essentially making Southwell’s very presence in the country a crime. Richard Topcliffe, a notorious priest-hunter and torturer (or one of his men), raped and seduced prisoner Anne Bellamy and manipulated her into arranging Southwell’s capture.

Arrested in 1592, he underwent frightful torture 10 times over the course of four days at Topcliffe’s hands, during which he steadfastly refused to betray his friends.

He then spent a month at the squalid Gatehouse Prison, after which he was transferred to the Tower of London for three years.

He was tried for treason and found guilty in February 1595. Before being hung, drawn, and quartered, he was said to have made the sign of the cross with his manacled hands, prayed for the queen, quoted a passage from Romans 14, and at last recited the “in manus tuas”: “Into Thy hands, Lord, I commend my spirit.” He was 33.

Servant of God Willi Graf (1918-1943), a German student under Nazism, was arrested for his involvement in the White Rose resistance movement and, after refusing to betray his friends under torture, was guillotined.

Born and raised in Saarbrücken, Graf served as an altar boy at St. Johann’s Basilica, and at age 15 recorded a Bible verse that would prove prophetic: “Be doers of the word and not hearers only, deluding yourselves” (James 1:22).

As a medical student at the University of Bonn, he was jailed for three weeks on a charge of illegal (i.e., Catholic) youth activities.

In Munich, he met like-minded students Alexander Schmorell and Hans Scholl, founders of the White Rose resistance movement. Their highly dangerous activity consisted of printing anti-Nazi leaflets and leaving them in telephone booths, mailing them to professors, and distributing them to other universities.

On Feb. 18, 1943, Jakob Schmid, a janitor at Ludwig-Maximilian University, spotted Scholl and his sister Sophie distributing leaflets and turned them over to the Gestapo. They were guillotined on Feb. 22.

Graf was arrested that same night. On April 19, he was convicted of high treason and sentenced to death.

He first spent six months in solitary confinement where, in spite of extensive interrogation and psychological torture by the Nazis, he never revealed the name of a comrade. He was beheaded at the age of 25 on Oct. 12.

In his diary, he had once written: “To be a Christian is perhaps the hardest thing to ever become in life.”

Servant of God Stefania Łącka (1914-1946), a journalist and teacher, was born to a family of peasant farmers in southern Poland. She graduated from a female teachers’ seminary in 1933, was active in the Marian Sodality, and — the action that would spell her doom — from 1934 to 1939, wrote and edited for Nasz Spraw, the weekly publication of the Diocese of Tarnów.

On April 16, 1941, the Nazis arrested Łącka and several of her associates. Under torture in prison, she refused to reveal the names of other team members.

She was transferred to Auschwitz in April 1942 and soon fell ill with typhus.

After recovering, she was assigned to the camp infirmary, where access to inmate files allowed her surreptitiously to remove a number of names from the crematorium lists. She was able to write to the families of others.

For the infants she couldn’t save, before they were killed along with their mothers, she baptized as many as she could, in secret and under penalty of death.

Such was her fortitude, kindness, and faith that she came to be known as “the earthly guardian angel of Auschwitz.”

At the conclusion of the war, Łącka was liberated and made her way home.

Weakened, however, by malnutrition, physical abuse, and the emotional trauma from her years in the camps, she died of tuberculosis on Nov. 7, 1946, at the age of 33.

Only God can judge actions forced by extreme duress.

What we do know is this: If those who betray a friend are relegated to the lowest circle of hell, then those who shed blood for their friends surely reside in the highest circle of heaven.