It’s difficult for people today to understand what a monumental cultural impact the film “Gone With the Wind” had on the American imagination. So the scandal the film created when Clark Gable’s Rhett Butler tells Vivien Leigh’s Scarlett O’Hara, “Frankly my dear, I don’t give a damn,” is also lost in the fog of popular culture’s tenuous memory.

A lot of words were not said in films then that are now routine on “family” television shows. But the march toward a coarser means of communication seems to be picking up the pace lately.

Tough language is nothing new in politics. President Harry S. Truman was renowned for his pointed, sometimes salty, tongue. There is a story about Truman showing a Democratic women’s group around the Rose Garden of the White House and telling them how much manure it took to get the roses looking like they did. After the tour, one of the women quietly asked Mrs. Truman why she didn’t counsel her husband to use a more delicate word besides “manure.” The woman suggested “fertilizer.” Mrs. Truman turned to the woman and said something to the effect of: “If you knew how long it has taken me to get him to say ‘manure,’ you wouldn’t be asking me that question.”

Now, I hear members of Congress, on the floor of the House of Representatives, openly use the language of the street, or gutter, as the case may be, as if talking in a locker room. And before I went through a second draft of this column, I saw an ad campaign for a potential California gubernatorial candidate that had the candidate proudly using a compound word that had to be bleeped.

Bad language seems to be spreading. I use too much of it myself, and it is part of my Lenten journey this year to keep my tongue in check. This does not mean I plan to let loose like a merchant Marine on April 21, but I want to be better. I want to keep my baser nature in check.

God has put a 6-year-old in my house, in my car, in just about every other place I can be, as a kind of lunchroom monitor for my wayward mouth. For that I am thankful.

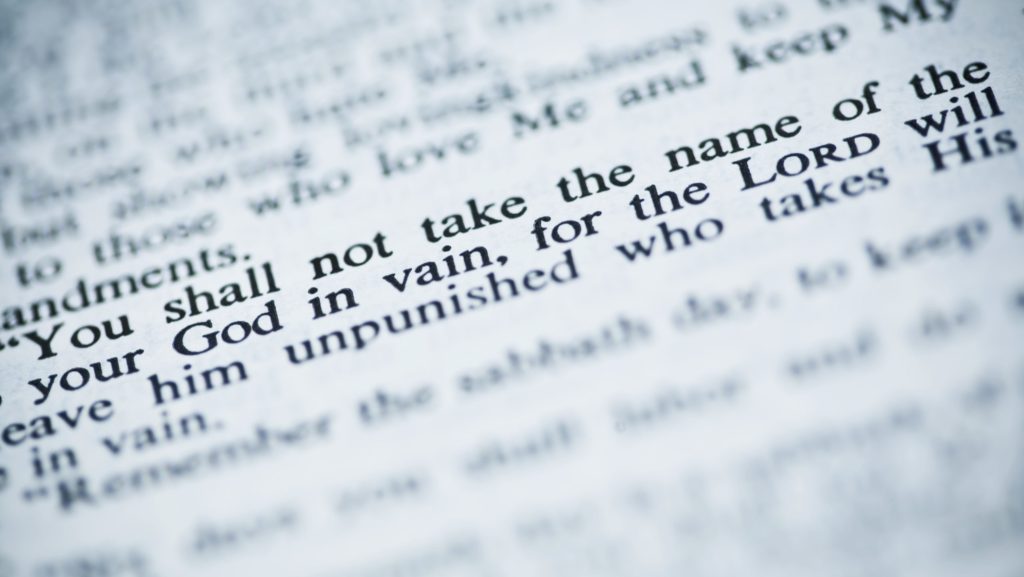

There is another form of foul language that has “blossomed” of late: the cavalier, everyday use of the Lord’s name. You hear it when someone is upset, when someone is elated, and when someone apparently just needs to fill the silence in a room.

I recently got up close and personal with just how pervasive punctuating sentences this way has become. I was in a room full of younger people talking about their viral video project, bringing attention to homeless services by creating vignettes based on a popular sitcom of the past. The video makers took on the personas and mannerisms of the sitcom characters. Some of the videos I saw were not half bad. One I did not see, though, had caused a problem: the Lord’s name was taken in vain, and someone who saw it online complained loudly.

None of the people in the room understood why this person was so upset. Several of them dismissed the complainer as some kind of rigid, uptight “church” lady.

I spoke up, telling them what they did was extremely offensive. All eyes were on me, and they were looking at me like I was from Mars. At that moment, I felt I was on Mars. You could almost hear the crackling sound of ice crystals forming on the office walls.

Reluctantly, the social media people agreed to reshoot their video, taking out the offending language. Of course, they did this by using the Lord’s name several more times.

These are good people. They are committed to doing good for others, and most of them put me to shame when it comes to corporal works of mercy. I felt isolated and validated at the same time, though. I looked like a fool, standing up for the Lord’s name.

Since then, I have followed the advice a good priest once gave me on how he dealt with people throwing the Lord’s name around, whether in a grocery store line, a gathering of friends, or even at a workplace. Upon hearing the Lord’s name, my priest friend would turn toward the sound, smile, and say a sincere “Amen.”