ROME — As the world mourns the loss of Queen Elizabeth II, there’s a grand irony about the reaction, which carries important lessons for all other potentates, up to and including popes: The respect and love people felt for Elizabeth was almost inversely proportional to the amount of hard power she actually wielded.

Yes, technically power in the United Kingdom is exercised in the name of Her Majesty’s government, and yes, technically, Elizabeth also reigned as the sovereign in 14 other states that are part of the Commonwealth of Nations.

Yet as early as the Magna Carta in 1215, the real power of the British monarchy has been progressively limited, to the point where today it’s almost entirely symbolic and ceremonial. For her 70 years on the throne, Elizabeth never had to make a controversial choice on tax policy, never had to decide whether or not to go to war, never sentenced anyone to prison, and never decided whether to join, or to exit, the European Union.

All those choices were made by officials invested with what Harvard political scientist Joseph Nye famously called “hard power,” meaning the power of the state to coerce compliance, while Elizabeth’s stock in trade was “soft power” — the moral authority that comes from representing ideals, values, and principles, from projecting personal dignity rather than realpolitik.

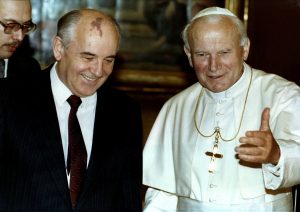

It’s intriguing to compare the spontaneous outpouring of grief at the death of Elizabeth to the somewhat more muted reaction to the loss of former Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev 10 days earlier.

Inside Russia, Gorbachev’s reputation is decidedly mixed, with many nationalists blaming him for essentially surrendering the Soviet empire. In the West, where Gorbachev’s stock always was higher — he even won the ultimate secular symbol of soft power, the Nobel Peace Prize, in 1990 — historians and politicians still give him mixed reviews.

Relatively little such ambivalence runs through the tributes now flowing in for Queen Elizabeth, because her legacy is largely unsullied by the inevitably compromised, and divisive, application of hard power.

Of course, this lesson also applies to the Vatican.

While English monarchs had become largely paper tigers by the 19th century, popes were still wielding absolute authority over their own dominion in the Papal States. There was a lay administration that took care of the nuts and bolts, but in practice life in the Papal States was determined by what disgruntled denizens referred to as “government by the priests.”

(As a footnote, it was the policy of the British government in the 19th century to support Italy’s unification drive, which would mean the collapse of the Papal States, but to do so only indirectly for fear of antagonizing the Catholic subjects of the United Kingdom. Including the populations of Ireland, Canada, Australia and Malta, Queen Victoria actually reigned over a Catholic empire far larger than the pope’s own.)

All that ended on Sept. 20, 1870, when Republican forces under King Emmanuel II poured through the Porta Pia, one of Rome’s traditional gates, and seized the city. When the dust settled, 49 Republican soldiers and 19 papal troops died that day, but the biggest casualty was the temporal power of the papacy.

Yet the truth is that the popes of the 152 years since have never been more internationally relevant, or popularly beloved. Despite possessing no real hard power, St. Pope John Paul II, for example, still managed to tower over his times — certainly the late Mikhail Gorbachev could have attested to the point.

Today, Pope Francis is a global icon and perhaps the world’s premier voice of conscience, for Catholics and non-Catholics alike, especially in defense of the poor, migrants, and refugees, and other marginalized groups.

In 1970, on the 100th anniversary of the breach of Porta Pia, St. Pope Paul VI gave a talk marking the occasion in which he called the loss of the papacy’s hard power “providential,” because it freed every pope since to play a more universal and humanitarian role in global affairs.

Indeed, a sure source of heartburn for any pope now is whenever they’re perceived to be trying to raise the ghosts of the Papal States.

Part of why the Vatican’s current “trial of the century” for financial corruption has proved so controversial, for example, is precisely because it seems a strange vestigial hangover from the past. In the Vatican’s system of civil justice even today, the pontiff exercises both supreme executive and judicial authority, in ways seemingly incompatible with modern standards of due process — not to mention, of course, the Catholic Church’s own social teaching.

Queen Elizabeth rarely made that mistake, exercising supreme discretion about anything that could be read as a political stance. When she did make statements, it was generally by example, such as the famous occasion in 1998 when Elizabeth unexpectedly drove Saudi Crown Prince Abdulla around her Scottish estate at a time when women weren’t allowed to drive in his own country.

One enduring lesson from Queen Elizabeth, therefore, is perhaps that the less hard power you possess, the more soft power you can amass. It’s a point the modern papacy began to assimilate a century and a half ago — even if it learned that lesson the hard way, literally down the barrel of a gun, and even if, in some particulars, it remains a work in progress.