People who write about religion sometimes refer to something they call “getting to know Jesus.” But read a little further, and you may discover that what is actually meant is “getting to know about Jesus.”

There’s nothing wrong with that, of course. Learning things about Jesus and his times — what it was like growing up in Nazareth, how people lived and worked and worshiped, the big religious and political issues of the day, who the Pharisees and Sadducees were and what they taught — can be very helpful. But it isn’t the same as getting to know Jesus himself.

This is the difference between learning about someone and becoming that person’s friend. The information is interesting and may even be useful, but it isn’t friendship.

Suppose, then, that Jesus really wants to be friends with you. (As a matter of fact, he does.) How can you reciprocate? How can you be friends with him?

One way — a very important, indeed indispensable way — is by meditation and prayer. So is receiving the sacraments, especially the Eucharist, which is the Real Presence (“body and blood, soul and divinity” an old formula says) of Jesus himself. But there also is a third way, not to be neglected by anyone who truly wants to know Jesus. It’s reading the Gospels.

The Second Vatican Council says of the gospels that they “faithfully hand on what Jesus, the Son of God … really did and taught.” As material for a friendship with Jesus Christ they are, quite simply, unsurpassed.

Reading the Gospels with the aim of getting to know Jesus and being his friend is far removed from the way we read a newspaper or watch TV news — distracted, superficial, skimming the surface but not absorbing very much. But before we look at some practical suggestions on how to read the Gospels, let me say something about the gospels themselves.

As everybody knows, there are four that are recognized as authentic and reliable — the Gospel of Matthew, the Gospel of Mark, the Gospel of Luke, and the Gospel of John. The first three — Matthew, Mark, and Luke — are known as the synoptic Gospels (“synoptic” means they tell the story from much the same viewpoint). John’s Gospel, by contrast, proceeds according to another pattern and tells us a great deal that the others leave out.

Each Gospel is significantly different from the other three. Matthew’s Gospel emphasizes Jesus’ teaching — for example, it contains the fullest version of the Sermon on the Mount — as well as his fulfillment of Old Testament prophecies. Mark’s, the shortest, appears to be based on the preaching of St. Peter himself. Luke’s Gospel contains famous parables like the good Samaritan and the prodigal son, and supplies information about the birth and childhood of Christ, leading some to believe Mary herself was one of its sources. And John places special emphasis on Jesus’ divinity, while tracing his growing conflict with the religious establishment in Jerusalem.

Every Sunday a passage from one of the four Gospels is read during Mass, thereby giving most Catholics at least some familiarity with them. But this reading of excerpts taken out of context has its limitations. Let me illustrate that with a true story.

A man I know — a well-educated, lifelong practicing Catholic who had heard the Gospels read in bits and pieces at Mass for years — finally sat down one day and read the gospel of Matthew straight through from beginning to end. When he finished, he exclaimed to others, “You know what? It’s telling a story!”

Indeed it is. The story is about the life of Jesus Christ.

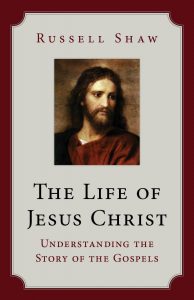

I had people like that man in mind in writing my book “The Life of Jesus Christ: Understanding the Story of the Gospels” (Our Sunday Visitor, $15.95). The book’s aim is to present the life of Christ in a single narrative that draws on all four Gospels while keeping commentary to the minimum necessary to understand the background of events.

This is hardly new. “Harmonies” of the Gospels, as they are called, have often been composed over the centuries as have many lives of Christ. And in modern times there have been some excellent movies and fictionalized accounts that flesh out the Gospels’ account.

The earliest “harmony” was produced in the second century AD by a Christian writer named Tatian and was widely used in the Church for a number of years. Unfortunately, though, Tatian apparently thought his work could replace the Gospels themselves. That definitely was not my aim — my small book is intended to help people read and understand the Gospels and the story they tell, not take their place.

Here, then, are a few suggestions for reading the Gospels as important aids in developing and maintaining a friendship with Jesus.

First of all, this should be something you do every day. I don’t suggest imitating the man I mentioned above by regularly reading one of the Gospels straight through from beginning to end. Five or 10 minutes a day are enough. But except in emergencies, that has to be a daily practice. At the rate of five or 10 minutes daily, you will cover all four of the Gospels several times each year.

Ideally, the best time to do it is early in the morning, before the predictable distractions of everyday life set it. Read slowly and thoughtfully. The point isn’t to see how much text you can cover in the allotted time but to absorb what you read. And although I caution against getting bogged down in Scripture commentaries, you will find it helpful to have at hand, for use as needed, a New Testament like the Ignatius Bible (Ignatius Press) or the Navarre Bible (Scepter Publishers), both of which contain good, helpful notes.

When you finish reading, spend some time — 15 minutes or so if you can manage it — thinking about what you’ve read and talking with Jesus about it. This is prayer, and it’s essential. A technique many people find helpful is to imagine themselves present at the events in the Gospel passage you read — a shepherd at the crib on Christmas, one of the crowd hearing the Sermon on the Mount, a servant at the Last Supper, or whatever it might be.

During the rest of the day, keep what you’ve read in the back of your mind and continue turning it over as time and circumstances permit. No daydreaming, though. Just a moment or two, then back to whatever you’re supposed to be doing here and now.

How important is reading the Gospels for someone who wants to know Jesus? An older writer says this: “For devout souls, each utterance, each act of the Master holds a special grace that facilitates the practice of the virtues. … This sort of reading is a meditation, a loving conversation with Jesus, and souls emerge from it determined more than ever to follow him who is the object of their admiration and their love.”

The language is old-fashioned, but the idea is eminently sound. If you’re already reading the Gospels like this, keep it up. If you aren’t, Lent is a great time to start. Books alone won’t make anybody friends with Jesus, but good books can help, and the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John are the biggest help of all.

But let me give the last word on the subject to the Beloved Disciple, St. John, near the conclusion of his Gospel.

“Now Jesus did many other signs in the presence of his disciples, which are not written in this book; but these are written that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that believing you may have life in his name” (John 20:30–31).