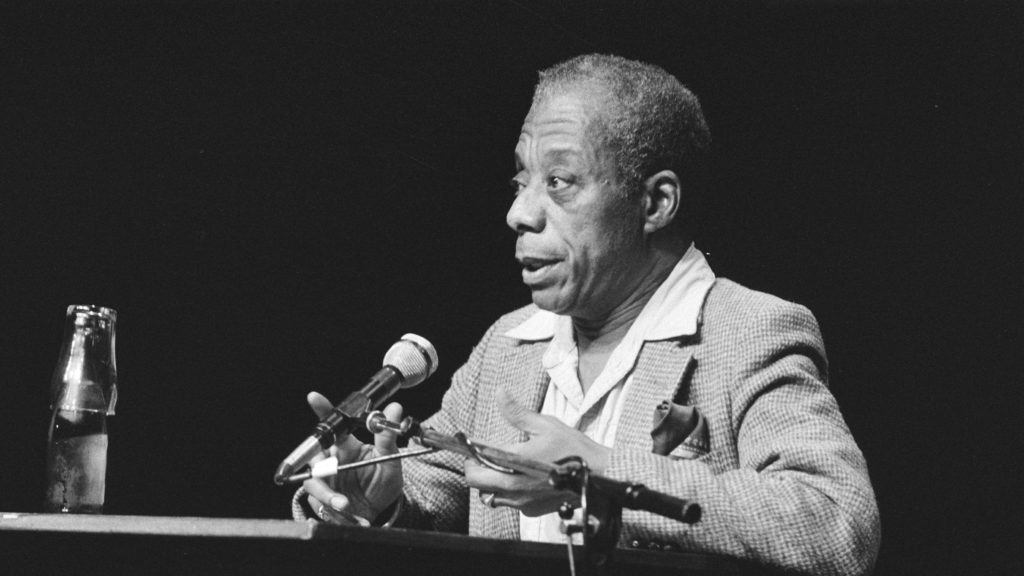

Recent assessments of the great American novelist and essayist James Baldwin (including a new biography by Nicholas Boggs titled “James Baldwin: A Love Story”), tend to emphasize his unconventional lifestyle and cast him as a kind of “woke” icon.

That emphasis turns a blind eye to the writer’s powerful critique of abortion as something the rich want to impose on the poor.

“The Devil Finds Work” is a 1976 book-long essay on American film that combines Baldwin’s personal experience as a movie-watcher and a wonderful criticism of our cinematic culture as developed from the 1930s to the 1970s through the prism of an African American sensibility.

There are several movies treated in the essay, all charged with symbolic resonance. But Baldwin’s take on the 1935 MGM movie “A Tale of Two Cities” (inspired by the Charles Dickens novel of the same name) was the one that most captured my attention.

Baldwin recalls that the end of that film, which takes place before and during the French Revolution, features a text from Scripture: “I am the resurrection and the life, saith the Lord: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall live, and he that believeth in me shall never die.”

The writer then admits: “I had lived with this text all my life, which made encountering it on the screen of the Lincoln Theater absolutely astounding.”

In the movie, Dr. Alexandre Manette, a prisoner in the Bastille, wrote a document about witnessing the callous killing of a young boy by a French aristocrat whose carriage races through a village.

Baldwin quotes Dickens, who in his book has Manette say: “We were so robbed, and hunted, and were made so poor, that our father told us it was a dreadful thing to bring a child into this world, and that what we should most pray for was that our women might be barren and our miserable race die out.”

Here Baldwin takes issue with Dickens.

“The wretched of the earth do not decide to become extinct, they resolve on the contrary, to multiply: life is their only weapon against life, life is all they have,” Baldwin writes.

He continues: “This is why the dispossessed and starving will never be convinced (though some may be coerced) by the population-control programs of the civilized. I have watched the dispossessed and starving laboring in the fields which others own, with their transistor radios at their ear, all day long: so they learn, for example, along with equally weighty matters, that the Pope, one of the heads of the civilized world, forbids to the civilized that abortion which is being, literally, forced on them, the wretched.”

Speaking of the “civilized” promoters of the destruction of life in the womb — before governments like our own began pushing an abortion agenda on the developing world – Baldwin says, “these people are not to be taken seriously when they speak of the ‘sanctity’ of human life… There is a ‘sanctity’ involved with bringing a child into this world: it is better than bombing one out of it.

“Dreadful indeed it is to see a starving child, but the answer to that is not to prevent the child’s arrival but to restructure the world so that the child can live in it: so that the ‘vital interest’ of the world becomes nothing less than the life of the child.”

Abortion was legal in the U.S. when Baldwin wrote those words. His talk about the resistance of the poor of the world to abortion applies more aptly now to the countries of Africa, where life in the womb is less threatened than in the United States. What Baldwin saw as the attempt of the “civilized elites” who wanted to coerce the poor to abort their babies has not stopped, although the methods may have changed a bit. Especially this is a problem for some minorities in the United States. The prevailing anti-values of the culture put pressure on minorities about abortion.

According to statistics from the Center for Disease Control, Black Americans make up 11.6% of the population but accounted for 41.5% of abortions in 2021. Hispanics, 19% of the population, accounted for 21.8% of the country’s abortions.

To put these statistics in other terms, of one thousand black women, 23.8 have had an abortion, of one thousand Hispanics, 11.7, and of one thousand white women, 6.6.

I was surprised to come upon an issue like abortion in a volume of film criticism from the 1970s, especially one by James Baldwin. Fifty years later it is still an issue, even after the reversal of Roe v. Wade. If we pretend to revere human life at all stages, we cannot be indifferent to the hecatombs of aborted children. It continues to be America’s tragedy and America’s sin. Tragically, Baldwin proved to be overly optimistic in predicting that the poor would resist the message of the “civilized.”

Recently I read the searing poem of Gwendolyn Brooks, an African American poet who won a Pulitzer Prize who was made Poet Laureate of the United States.

Titled “the mother,” it begins: “Abortions will not let you forget/ You remember the children you got that you did not get…I have heard in the voices of the wind the voices of my dim killed children.”

Baldwin was a genius essayist, but his work was much more coherent than his life, in which struggle and suffering rarely let up. Creative people are complicated and even self-contradictory. Now that he seems to be back in vogue almost 40 years after his death, his new biography will probably burnish his reputation as a rebel against traditional values.

But even through windows that have been cracked, there is a startling and important view sometimes. It is hard to hold Percy Bysshe Shelley’s dictum that “poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world,” but sometimes they are its conscience. Baldwin and Brooks both remind us that our complacency about abortion is a defeat for the truth and a victory for inhumanity.