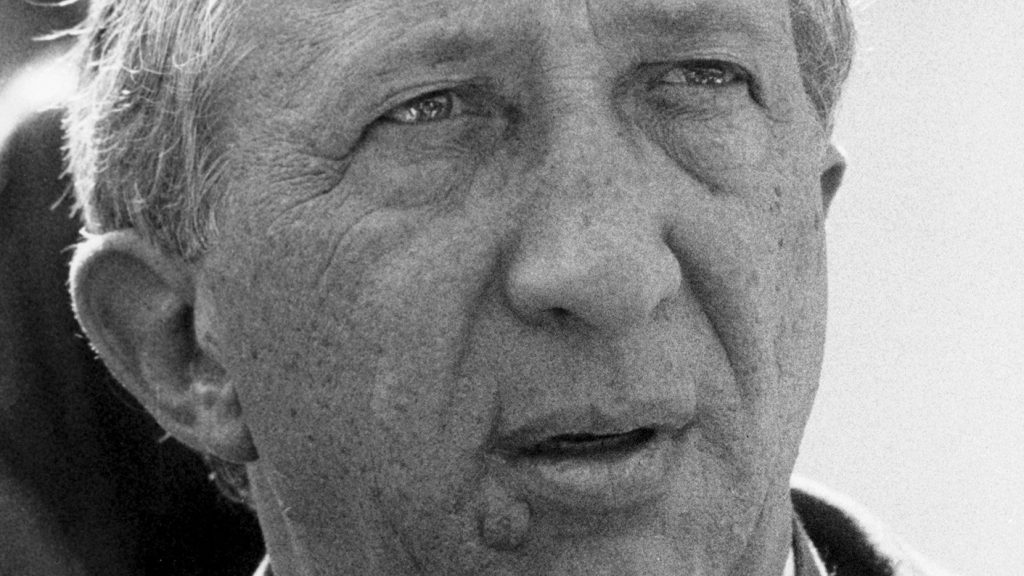

ROME — Were he still alive, Italian Father Luigi Giussani, founder of the Communion and Liberation movement, would be 100 years old on Oct. 15. Ever the realist, it probably wouldn’t surprise Father Giussani a bit to discover that his community today remains a mix of light and shadow, of great promise and, honestly, no small amount of heartache.

The heartache, at least, is relatively easy to spot.

Two years ago, a women’s group called “Memores Domini” (“Remember the Lord”), which is part of the broader Communion and Liberation constellation, essentially was placed into receivership under the Vatican’s Dicastery for Family, Laity and Life, allegedly for being slow to adopt requested reforms.

Last year, Spanish Father Julián Carrón abruptly stepped down as the leader of Communion and Liberation after having just been reelected, after new Vatican rules imposed term limits on the heads of lay movements, which some saw as directed specifically at the “ciellini” (“members of CL”). At the time, it seemed reaction within the movement was split between members who never really cared for Father Carrón, who’d been hand-picked by Father Giussani as his successor but whom some regarded as overly “soft,” and by other members who resented the Vatican intrusion.

In June, a letter from Cardinal Kevin Farrell to Communion and Liberation’s leadership was revealed, accusing the group of fostering “a climate of distrust of the Church and resistance to its indications; a strong personalism; internal divisions and manipulative logic; [and] a broad dissent regarding the interventions and decisions of ecclesiastical authority.”

As if all that weren’t enough, Roberto Formigoni, a former governor of Italy’s Lombardy region and probably the highest-profile “cielino” in the country, was recently in the news again for being granted a sort of work release to teach Italian to foreign nuns to serve out the rest of his jail term following a 2019 conviction in a bribery and corruption case involving a hospital in Milan.

In other words, it’s been a bit of a tough run for the disciples of Father Giussani over the last few years.

Founded by Father Giussani in 1954, the original idea of Communion and Liberation was to foster an ardor for evangelization and the engagement of culture, animated by Giussani’s emphasis on faith as an encounter with Christ. His classic book, “The Religious Sense” in 1966, was an attempt to argue that reason in its broadest sense, meaning critical reflection on experience, leads one naturally to God and to Christ.

Father Giussani attracted many admirers over the years, including the future Pope Benedict XVI, who preached at Father Giussani’s funeral Mass in 2005, and whose own personal household is served by four women from “Memores Domini.”

Yet Communion and Liberation also came to be seen as a beachhead for conservative Catholic sentiment and resistance, which made it something of a loyal opposition in Milan during the years of Cardinal Carlo Maria Martini and his progressive leadership. That reputation followed Communion and Liberation into the Pope Francis papacy, and it didn’t help that early on a prominent Italian bishop and former top aide to Father Giussani, Archbishop Luigi Negri, was quoted as calling a couple of the new pope’s episcopal appointments “disasters” and praying for his early death.

(Negri initially refused to comment, then denied saying anything about Pope Francis’ death, then said he’d been taken out of context and misunderstood. He asked for an audience with the pope to explain himself, but the meeting never occurred before his death on New Year’s Eve in 2021.)

The perceived tension between the pontiff and the movement has produced headlines such as this one, from Italy’s Il Foglio in June of this year: “Why does Francis not love Communion and Liberation?”

Yet despite it all, the movement founded by Father Giussani today is present in more than 90 countries around the world. Its major annual event, a meeting in the seaside Italian city of Rimini, is still the highlight of the Italian political and cultural calendar — this year it was attended, among others, by outgoing Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi, who used it almost as a platform for his valedictory address.

Communion and Liberation also operates the Banco Alimentare, one of Europe’s largest charitable operations and private food banks, as well as a related Banco Farmaceutico, and is also the inspiration for Avsi, a multifaceted charity with more than 2,000 staff and a network of more than 60 organizations. There are also dozens of schools around the world inspired by the pedagogical and educational insights of Father Giussani.

Over the course of this year, Communion and Liberation also has a series of major events planned to commemorate the centenary of Father Giussani’s birth.

A famous story has it that in 1971, Father Giussani met the storied Swiss theologian Father Hans Urs von Balthasar, who was delivering a series of spiritual exercises for university groups related to the movement. As the narrative has it, Father Giussani expressed admiration to Father von Balthasar for his intellectual accomplishments, to which Father von Balthasar supposedly responded, “Yes, yes, but you have created a people.”

That was especially high praise coming from Father von Balthasar, who had tried his hand at founding a movement himself, the Community of St. John, but it never really got off the ground.

Indeed, Father Giussani has created a people. Admittedly, it’s a people covering some rocky ground right now, and perhaps with some course corrections to execute.

But it’s still a people with major accomplishments to its credit, and full of the promise of more to come — and one has to imagine that Father Giussani, with his emphasis on the clear-eyed acknowledgment of experience, probably wouldn’t be surprised by any of it.