The Bible and Christian tradition are definite — heaven is for real and waiting for us. We’re just not quite sure what it’s going to be like

Heaven made the evening news in mid-April, when a small boy approached the pope and asked if his deceased father, an atheist, was in heaven.

The pope, addressing all the children of the boy’s parish, didn’t quite answer the question, but gave everyone the principles for thinking about it. “God is the one who says who goes to heaven,” he explained. And then he asked: “God has a dad’s heart. … Does God abandon his children when they are good?”

The Holy Father’s response was spontaneous, but an accurate summary of the Church’s teaching on the matter.

Skeptics scoff and say that heaven is the Church’s bribe to get good behavior out of reluctant Christians. A cynic of the last century reduced it to the promise of “pie in the sky when you die.”

But the truth is that the official Church has said surprisingly little about the matter. The Catechism of the Catholic Church offers a minimal definition and seven points (out of the book’s total of 2,865). Earthly concerns, such as “The Duties of Parents,” get far more attention. And the early Christians managed to convert the Roman Empire without dwelling much on heaven or hell.

Still, that schoolboy spoke for billions of people when he brought his question to the pope. We are a society preoccupied by retirement, pensions and elder care — providing for the future. But what comes afterward, and how should we prepare for that?

Heaven in the Bible

The Bible, like the Church, is definite in its promise but modest in its description of heaven.

Jesus said, “I go to prepare a place for you … that where I am you may be also” (John 14:1-2).

But the apostles ventured to say little about that “place.” St. Paul quoted the prophet Isaiah: “Eye has not seen, and ear has not heard … what God has prepared for those who love him” (1 Corinthians 2:9; Isaiah 64:3).

St. John is just as respectful of the limits of human language and imagination: “Beloved, we are God’s children now; what we shall be has not yet been revealed. We do know that when it is revealed we shall be like him, for we shall see him as he is” (1 John 3:2).

Pope Benedict XVI spelled out the difficulties of talking about heaven. We are finite creatures, always keenly aware of the passing of time. How can we begin to conceive of life shared with a God who is infinite and eternal?

“To imagine ourselves outside the temporality that imprisons us and in some way to sense that eternity is not an unending succession of days in the calendar, but something more like the supreme moment of satisfaction, in which totality embraces us and we embrace totality — this we can only attempt. It would be like plunging into the ocean of infinite love, a moment in which time — the before and after — no longer exists. We can only attempt to grasp the idea that such a moment is life in the full sense, a plunging ever anew into the vastness of being, in which we are simply overwhelmed with joy.”

When the mind encounters limits, it seeks metaphors. In Scripture we find heaven compared to a banquet (Isaiah 25:6, Revelation 19:9) — a feast where hunger is fed to perfect contentment.

The Bible also presents heaven as a city (Revelation 3:12 and 21:2). This means that it is a society, in which we will know the company of loved ones. Yet we will not suffer the grief and misunderstandings that trouble our relationships in earthly life (see Revelation 21:4). In heaven we will love, and be loved, as we cannot here.

An ‘argument from desire’

“At present we see indistinctly, as in a mirror, but then face to face. At present I know partially; then I shall know fully, as I am fully known” (1 Corinthians 13:12).

Though now we can only glimpse it, we can still be sure there is a heaven. It has, after all, been revealed by God, who cannot deceive. God took flesh in Christ in order to conquer death. He rose from the tomb, furthermore, as “first fruits” (1 Corinthians 15:20) that bespeak a full harvest. So we, too, will rise as he did.

If we are faithful we will take our place with him. All of this has been promised by God, and so we can hold it with certain faith. There are strong supernatural reasons, then, for our hope in heaven.

But there are also good natural reasons. Philosophers propose an “argument from desire.” We are built, they say, with certain drives, and each drive has its satisfaction. Hunger is satisfied by eating, thirst by drinking, sexual desire by sexual union and fatigue by sleep. These conditions are innate and universal in healthy people. The means of their satisfaction are widely available.

From this observation, the contemporary philosopher Peter Kreeft proceeds to a second premise. He notes that “there exists in us a desire which nothing in time, nothing on earth, no creature can satisfy.” And so he concludes: “There must exist something more than time, earth and creatures, which can satisfy this desire.”

And that something is called heaven — unending life with God.

C.S. Lewis made a similar argument in the book “Mere Christianity”: “If I find in myself a desire which no experience in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world.”

The desire for immortality is at least as common as the desire for sex. We would not experience it if its satisfaction were unattainable.

St. Augustine summarized the matter rather perfectly more than a millennium and a half ago: “You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our hearts are restless until they rest in you.” Heaven is, says the Catechism, “the ultimate end and fulfillment of the deepest human longings, the state of supreme, definitive happiness.”

Heaven now

We speak of heaven colloquially as a “place” — television calls it “the good place” — but bodiless spirits don’t occupy space the way bodies do.

Heaven cannot be marked by a pin on any map of the universe, but that doesn’t mean it is merely a concept. We can speak of it only in metaphors, but that doesn’t mean that heaven is simply a metaphor.

St. Pope John Paul II said, “Heaven is neither an abstraction nor a physical place in the clouds, but a living, personal relationship with the Holy Trinity. It is our meeting with the Father which takes place in the risen Christ through the communion of the Holy Spirit.”

Heaven is our share in the life that is proper to God, who is pure spirit. When we point upward to signify its “location,” when we profess that Jesus “ascended into heaven,” we are signaling God’s transcendence of the world and time — and our hope to join him.

Heaven belongs to God alone by nature, and it is his alone by right. But in his mercy he has shared it with us. This is the deepest meaning of salvation: that we have become divinized, that we “have come to share in the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:4).

What is God’s by right he has given as a gift, a grace, from the moment of our baptism.

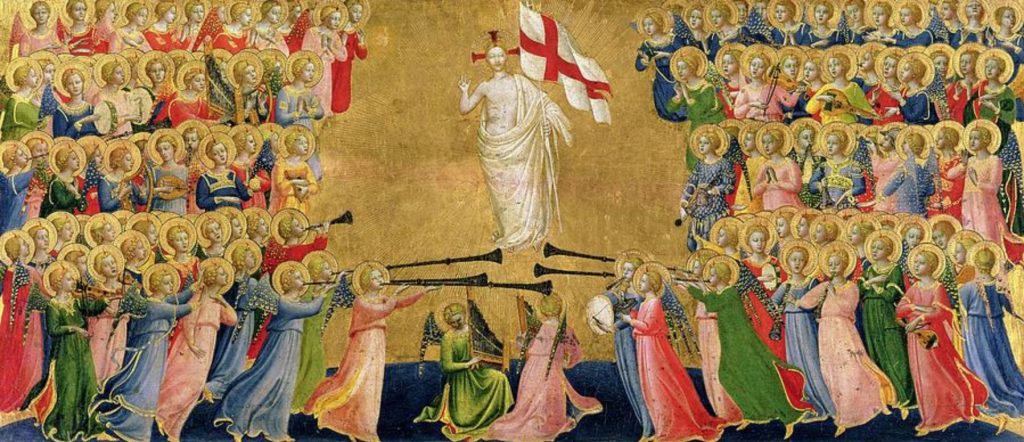

Thus it’s a mistake to think of heaven exclusively as “the afterlife.” We acknowledge the presence of all of heaven, for example — “all the angels and saints” — whenever we go to Mass. To live in the state of grace is to begin our heaven right now.

When we receive Holy Communion, we anticipate heaven. We receive God in all his glory, though we cannot see him or otherwise sense him as the saints do in heaven. Nevertheless, we are already sharing his life.

When we give ourselves generously in charity, we are living God’s life, because God is charity. “We have come to know and to believe in the love God has for us. God is love, and whoever remains in love remains in God and God in him” (1 John 4:16).

Everything in the life of faith — all of Catholic morality and piety — is designed to bring us closer to heaven while we’re still on earth. If we live faithfully, the transition should go more smoothly at the end; for our charitable deeds go with us (see Revelation 14:13 and 19:8), but “nothing unclean will enter” (Revelation 21:27).

If we go to our death clinging to our sins, we may still “be saved, but only as through fire” (1 Corinthians 3:15). That’s the mercy of purgatory, which makes us ready for the presence of God.

Heaven is a gift, a grace. It’s granted and given. But, like any gift, it must be accepted. It must be chosen and taken. God is love, and heaven is our share in God’s love. And love cannot be coerced or forced.

In his long discourse on the Bread of Life, Jesus said, “I will not reject anyone who comes to me” (John 6:37). And that is a perfect expression of our freedom. God does not receive us as cattle on a conveyor belt. He calls us, and if we respond he will not reject us.

If we respond, we come to know heaven, as a judgment and a mercy, a gift and a choice — as Pope Francis presented it to the little children who came to him in Rome.

Christ has “ascended into heaven.” He has promised to prepare a “place” for us, that we might be where he is, that we might fully accept our share in his divine nature. We live by that promise.

rn

rn

rn

Mike Aquilina is a contributing editor of Angelus News and the author of more than 40 books, including “Angels of God: The Bible, the Church and the Heavenly Hosts” (Servant, $16).

Interested in more? Subscribe to Angelus News to get daily articles sent to your inbox.