James Dickson Innes (1887-1914) was a British landscape painter of whom I learned while thumbing through “Pastures Green and Satanic Mills: The British Passion for Landscape,” by Tim Barringer and Oliver Fairclough. All the landscapes spoke to me, but Innes’, of a mountain in North Wales, made my heart stop.

The mountain in question is “Arenig Fawr” (“Great High Ground”) which, 2,800 feet high and twin-peaked, is located in a wind-blown, desolate spot in Snowdonia.

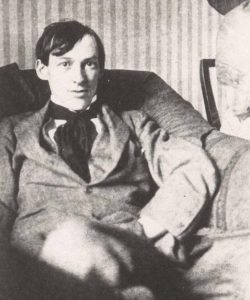

Born in Llanelli, Innes studied at Carmarthen Art School and the Slade. A colleague there noted that he “was of middle height, black haired and thin featured, handsome to many people ... there may have been something satanic in his look.” He was already dying of tuberculosis, having been diagnosed at 21.

Shortly thereafter, Innes traveled to North Wales and was captivated — obsessed might be a better word — by “Arenig Fawr’s” brooding majesty. He painted impulsively and passionately, almost as if he and the mountain shared a secret language.

His sensibility, talent, and bold, saturated colors — vermilion, citron, Prussian blue — were noticed by the far better known (and far more notorious) Post-Impressionist painter Augustus John, nine years Innes’ senior.

John ended up moving to North Wales himself, where he and Innes became friends, rented a stone farmhouse, drank, caroused, and tramped the cold, dank mountains. But above all, they painted. Their work was exhibited in New York in 1913, alongside that of Cézanne, Gauguin, and Picasso.

While John was robust, Innes was frail, with feverish eyes. Far from slowing him down, Innes’ increasingly poor health instead spurred him to drink more, carouse more, and especially to paint more.

He was rumored, knowing he was dying, to have buried at “Arenig Fawr’s” summit “Moel yr Eglwys” (“Bare hill of the church”) a chest of letters from a love who had spurned him. He was gone within six months, at the age of 27.

You can learn about Innes’ work and life through streaming the free BBC documentary “The Mountain that Had to be Painted.” The film features clips from fellow artists, scholars, and Michael Holroyd, John’s biographer. Painters especially feel an almost sacred connection to “Arenig Fawr” and simply want to stand where Innes stood when he saw and painted.

Innes’ dying-gasp output reminds me of some of the many other artists who wrote, composed, and painted while they were dying.

In “The Wild Places,” for example, British writer and naturalist Robert Macfarlane observes: “Between 1946 and 1948, [George] Orwell spent six months of each year living and working in Barnhill, an exceptionally isolated stone-built cottage set on the tawny moors of the northern tip of the Scottish island of Jura.”

Reaching the cottage required a 48-hour journey and a 7-mile walk. Orwell fished, swam, farmed, and kept a peat fire burning for warmth. There, he also wrote his most iconic book: “Nineteen Eighty-Four.”

“The price of this vision, though, was his life. For Jura killed Orwell in the end. His fragile lungs, unable to stand the island’s dampnesses and colds, succumbed to tuberculosis, of which he died in 1950.”

Franz Kafka penned two of his finest works — “A Hunger Artist” and “The Castle” — also while dying of tuberculosis. Nothing kept him from working, not the collapsed lungs that made him feel like he was breathing splinters of glass, not the tormented nerves that had plagued him all his life. “God doesn’t want me to write, but I — I must … and there’s more anguish in it than you can imagine,” he wrote to a friend.

Dennis Potter, the brilliant British TV writer (“The Singing Detective,” “Pennies From Heaven”) suffered his entire career from an excruciating condition called psoriatic arthropathy. He wore pajamas under his clothes to contain the clouds of flaking skin, turned in scripts splattered with blood and cortisone cream and, when his hand was too crabbed with arthritis to hold a pen, strapped the pen on and continued writing anyway.

Upon being diagnosed with inoperable cancer, he established a grueling, nonstop work schedule that not only enabled him to finish the last two works he’d planned, but to go on and write more.

Swollen with cortisone, her joints crippled, novelist and short story writer Flannery O’Connor worked fiercely through years of the lupus that would kill her at the age of 39. When her mother urged her to go to Lourdes, she reluctantly did, writing afterward to a friend, “I prayed there for the novel I was working on, not for my bones, which I care about less.”

Three weeks before dying, she wrote to a friend, “I’m still in bed but I climb out of it into the typewriter about 2 hours every morning.” Two weeks before: “I’m still puttering on my story that I thought I’d finished but not long at a time. I go across the room and I’m exhausted.”

We’re at the end of summer, on the cusp of the harvest season. Many of us experience a strange surge of energy this time of year, an archetypal urge to gather in stores for the winter before going underground, metaphorically dying, and emerging — we hope — “newly born,” in the spring.

Anyone can tear things down. It takes a hero and possibly a saint to create, to endure, to continue creating, to finish the race — even knowing that next year, spring won’t come.