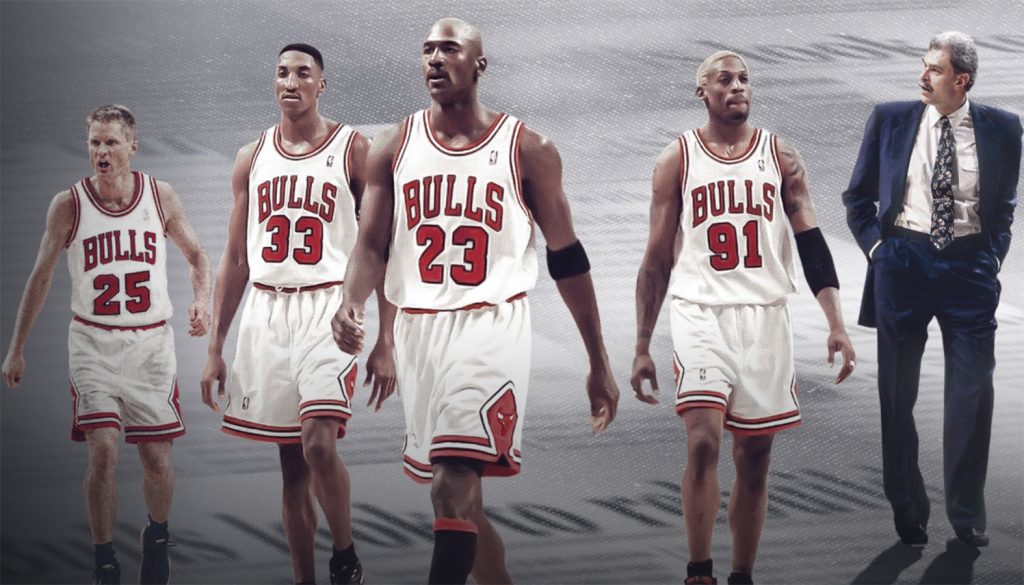

Being starved of any form of live sports, and after watching more than one replay of the 1988 Dodgers World Series game where Kirk Gibson hit the most stupendous homerun in the stadium’s history, I watched the ESPN 10-part series about Michael Jordan.

It was presented in documentary form, but a documentary it was not. How could it be, when the subject of the film had absolute control over what was going to be said and how it was going to be said?

It was as reality-based as the audience in a game show. In other words, it was orchestrated, choreographed, and molded for only one purpose: to tell the story as seen through the unbending eyes of the protagonist, Michael Jordan.

The first two definitions of the very word “protagonist” both serve to describe Michael Jordan’s role in these 10 segments of television: the leading character, or one of the major characters, in a drama, movie, novel, or other fictional text, and the main figure, or one of the most prominent figures, in a real situation.

In the year 2020 AO (Age of Oprah), where everyone is entitled not only to their own opinions but their own “truths” as well, Michael Jordan dominated the television screen during each segment of “The Last Dance” as powerfully as he dominated the basketball court in his prime. But in the aftermath, it became quite unclear where Michael Jordan’s truth stopped and somebody else’s truth began.

Jordan’s almost obsessive need to control every facet of the narrative had the opposite effect, at least on me. We got to see a side of Michael Jordan that I’m not sure he wanted exposed. Then again, even if that were the case, I don’t think someone as driven and as self-confident as Michael Jordan is would care all that much.

“The Last Dance” is another example of how it is nearly impossible these days to manage and perpetrate a legend. That is both a good thing and a bad thing. Maybe in a thousand years a new kind of mythic narrative will develop around the likes of Michael Jordan, but after watching the multipart, self-directed story of his career that was promoted as the real story behind the headlines, I was left with a distinct sense that I was being forced fed an image.

From reading other reviews and commentators about this series, the saddest thing I took away from it was that Jordan’s “win or you’re nothing” attitude was not seen as a defect, but something devoutly to wish for by a lot of people.

There is another ESPN series that has been around for a while called “30 For 30,” which takes an in-depth look into a sporting event, a sporting personality, or some other social event with a sports tie-in. Its latest offering deals with the famous cyclist Lance Armstrong.

Now I know nothing about the Tour de France, and frankly, that’s the way I like it. I have already jammed the limited brain space I have with too much football, baseball, basketball, and hockey to find room for any other sport. And to be honest, watching a bunch of guys ride their bikes, as pretty as the French countryside is, sends me looking at my streaming service schedule to see if there’s a cornhole tournament in Spokane I might be missing.

But the two-part Lance Armstrong “30 For 30” episodes do not require foreknowledge, or even the slightest interest in bicycle racing — got them covered on both of those points. One only has to have an interest in human nature to find it compelling television.

Like Jordan, Armstrong dominated his field. Unlike Jordan, Armstrong cheated his way to the top. Whereas Jordan’s intense sense of competitiveness and ego the size of a school bus reconstructs and remolds truth as he sees it in his television show, Armstrong, alas, is a mere mortal and must confront a faceless inquisitor of a filmmaker and answer questions that were not always to his liking.

I’m sure a body language expert could write volumes on the way Armstrong physically reacted to the less seemly elements of his once spotless reputation, now sullied by drug-doping accusations. Armstrong, unlike Jordan, has a scarlet “C” (for cheater) emblazoned on his chest.

But in another way, this “legend” is a mirror image of Jordan when it comes to maintaining his own version of his truth. It makes prisoners of them both. Facts are stubborn things and so is the real truth. There never has been, or ever will be a “her” truth and a “his” truth, but only the truth, and that is the only truth that will make one free.