I first came upon the painter Horace Pippin on a trip several years ago to Philadelphia’s Barnes Foundation, an art collection and educational institution boasting one of the world’s greatest collections of impressionist, post-impressionist, and early modernist paintings.

Albert C. Barnes (1872-1951), a wealthy businessman with cash to burn, in his 40s started traveling to Europe to study and collect art.

Barnes was irascible, eccentric, and passionate. He hung his collection according to his own idiosyncratic tastes, and left strict instructions in his will that the works were to be left exactly as he had arranged them upon his death.

The subsequent lawsuits, the 2012 moving of the collection to its current site on Benjamin Franklin Parkway (critic Jed Perl observed: “The Barnes Foundation, that grand old curmudgeonly lion of a museum, has been turned into what may be the world’s most elegant petting zoo”), and ongoing squabbles make for fascinating reading.

But way more fascinating are the works themselves. Renoirs alone number 181; Cézannes 69. The collection includes more than 4,000 objects, including Native American ceramics, jewelry and textiles, ancient Egyptian, Greek, and Roman art, and wrought iron.

In the early 1920s, Barnes became interested in the Harlem Renaissance. He purchased more than 100 African masks and sculptures from the French art dealer Paul Guillaume.

He also discovered the work of Horace Pippin (1888-1946), a self-taught painter from West Chester, Pennsylvania, who is today considered one of the 20th century’s foremost African-American artists.

Pippin came from a family of manual laborers and domestics. During World War I, he enlisted in the Army and in France suffered a right shoulder wound that resulted in permanent injury. Ever after, he would have to prop his right arm up with the left in order to hold a brush.

In 1920, he married Jennie Fetherstone Wade Giles, the couple settled in West Chester, and Pippins began to paint in earnest.

“Tell My Heart: The Story of Horace Pippin” features 119 of Pippins’ paintings. Essays by, among others, Judith E. Stein (“An American Original”), Cornel West (“Horace Pippin’s Challenge to Art Criticism”), Richard Powell (“Biblical and Spiritual Motifs”) provide cultural and artistic context.

His first works were scenes of war, the horrors of which had imprinted themselves upon Pippins’ psyche.

A black artist friend, Edward Lopez, observed of Pippin during those years: “At that time there were certain kinds of black men who I admired. … They had self-respect and [Pippin] had lots of self-respect. He knew he was strong.”

Early on, Pippin faced a crucial dilemma: Should he make race the defining feature, the organizing principle, of his art, and thus run the risk of the art becoming propaganda? Or should he honor his experience as a member of an oppressed race but paint from his experience of the human condition? Pippin chose the latter, steered his own course, and in the process achieved a freedom of spirit that many of us can only envy.

A 1945 photograph in profile reveals the soul of the man: Pippin gazes out at the world clear-eyed, dignified, noble, utterly sure of his purpose and place.

“It was as though he had clearly resolved to seek the benefits of self-esteem rather than critical praise in his ardent pursuit of the American Dream,” writes professor of art David C. Driskell. “He was comfortable being Horace Pippin, an artist with a different view of the world.”

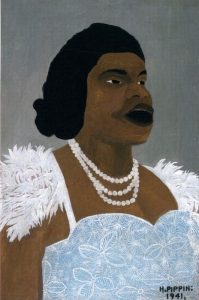

He did landscapes: trappers, fishers, squirrel hunters under brooding winter skies. He painted portraits of his wife, himself, and perhaps most famously of the singer Marian Anderson, resplendent in pearls, a blue strapless dress and a white feather boa. There were domestic scenes, still lifes, and depictions of racial violence.

He first came to prominence in 1938 when his work was included in the exhibition “Masters of Popular Painting.” His first solo show was in 1940 in Philadelphia. In 1943 he was invited to participate in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts’ annual exhibition and won the purchase prize with “John Brown Going to His Hanging.” In his lifetime he was included in several other major annual exhibitions at museums across the U.S.

Pippin, a member of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, also explored religious and spiritual themes. His “Holy Mountain” series (1944-1946) depicts scenes from the Old Testament.

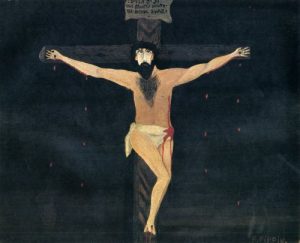

But his two best works may be “Christ (Crowned with Thorns)” (1938) and “The Crucifixion” (1943): the latter, Duke professor of art history Richard J. Powell notes, “conveys a Northern Renaissance-like sense of anguish and moral outrage.”

Christ’s chest hair makes him appear strangely human and vulnerable. A disembodied head of Satan leers from the lower left. Drops of red blood, against a near black background, fall one by one from Christ’s hands. The whole makes for a richness and depth to which the term “folk art” doesn’t nearly do justice.

“Pictures just come to my mind and I tell my heart to go ahead,” Pippin once said.

And in 1942, he told his friend Ed Lopez, “Ed, you know why I’m great? ... I don’t do what these white guys do. I don’t go around here making up a whole lot of stuff. I paint it exactly the way it is and exactly the way I see it.”