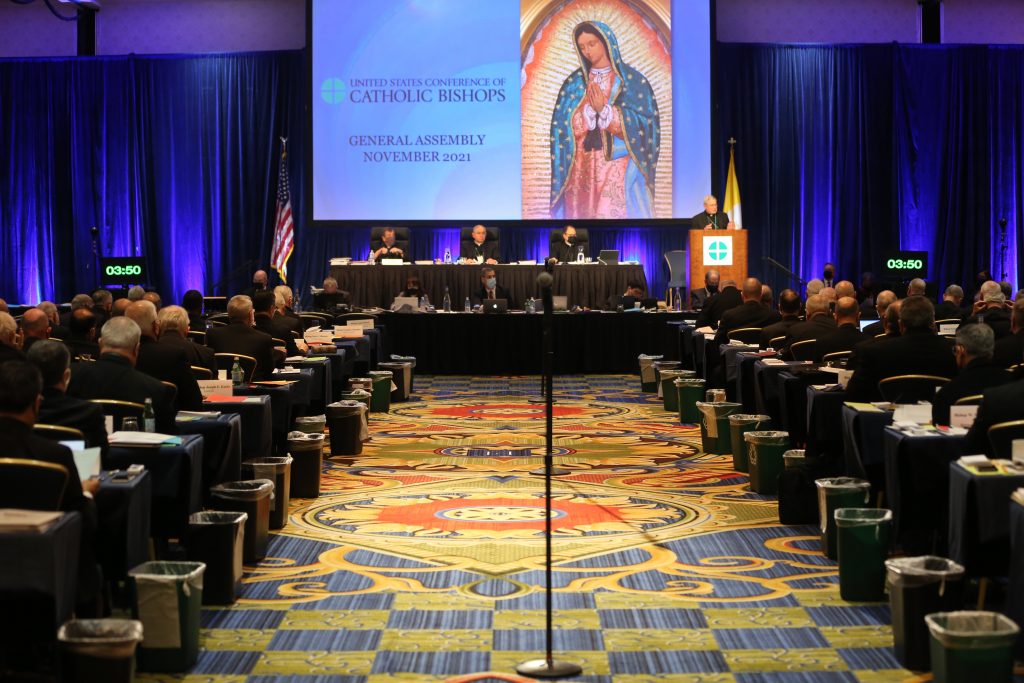

In mid-November the American bishops, gathered in general assembly, will choose a successor to Archbishop José H. Gomez of Los Angeles to serve a three-year term as president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. A new vice president and chairmen of several conference committees also will be elected during the meeting.

Except by the bishops themselves plus a handful of habitual bishop-watchers, the USCCB elections will probably not be much noted. But there are several issues of major importance for the future of the Church that need to be on the bishops’ agenda, and the results of the upcoming vote could go a long way to determining whether they make it there.

Three issues in particular stand out.

First, giving new direction to the Church’s involvement in pro-life issues in the wake of the Supreme Court decision last June overturning the 1973 ruling that legalized abortion.

While the ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization was a huge pro-life victory, but far from being the end of the struggle, it marked the start of a new phase for which the pro-life movement was apparently not well prepared.

What now? Fifty years ago the bishops adopted a Pastoral Plan for Pro-life Activities that provided guidance to dioceses in advancing the pro-life cause while hoping for what Dobbs has now accomplished — returning the abortion issue to the states.

In the post-Dobbs world the Church’s response needs to be comprehensively pro-life, including support for women with problems in pregnancy, tax relief, and other assistance for struggling families, rational gun control, immigration reform, abortion laws that have broad public support, and educational efforts that counter pro-abortion propaganda with attractive, fact-based messaging.

Second, exploring and explaining the meaning of synodality in a synodal Church.

Writing in America magazine, Father Louis J. Cameli, a coordinator of the synod process in Chicago, cited the “immense formational task” required to prepare people for this new ecclesial environment.

He couldn’t be more right. Many lay Catholics aren’t ready for the role abruptly being thrust on them by the Church’s current movement toward synodality. Without serious remedial action, it’s possible that — as seems already to have happened in Germany — synodality will fall prey to a minority eager to manipulate the process on behalf of their agenda.

Third, sketching elements of a master plan for allocating institutional and human resources in the new era of closures and contraction in which the Catholic Church, like other churches and religious groups, now finds itself.

Over the past half-century, the bishops’ conference has issued innumerable statements about all manner of political and social issues, but it has yet to address the crisis now confronting the Church. Indeed, it was almost a novelty for the bishops two years ago to launch a “Eucharistic Revival” project to address the decline in faith in and appreciation for the Blessed Sacrament (a problem that polling had already identified a full 30 years earlier).

Now American Catholicism is in a multidimensional crisis that includes steep declines in priests, students in Catholic schools and religious education, couples entering Catholic marriages, and infant baptisms, the slow-motion disappearance of most women’s religious communities, and much else besides. Cold comfort indeed that non-Catholic churches in America face similar issues.

I don’t expect the USCCB to wave a magic wand and solve these problems. For canonical reasons, many can only be addressed at the diocesan level. But the episcopal conference has a role to play in information sharing, planning, and coordination. November would be a good time to start.