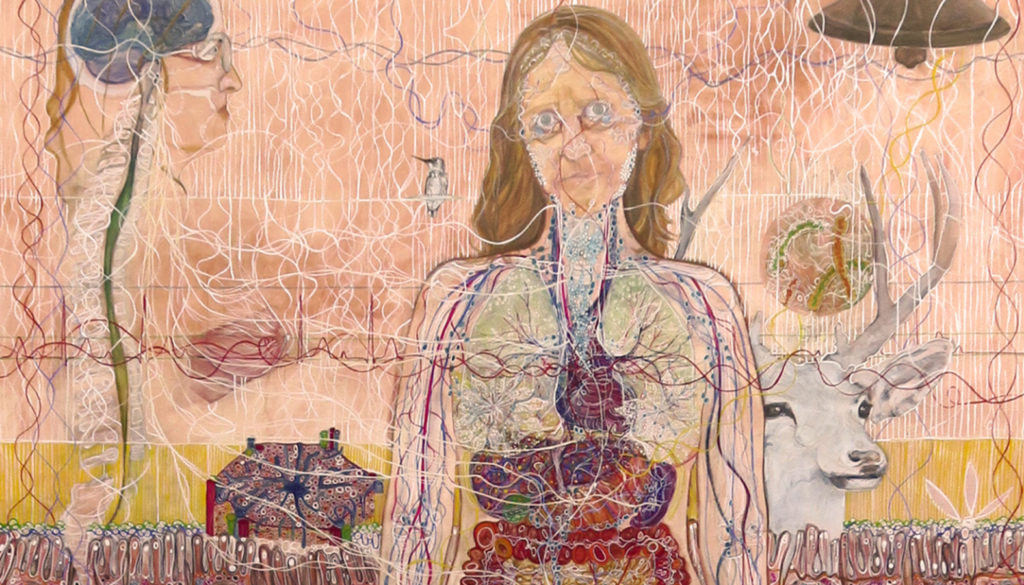

Phoenix-based artist Monica Aissa Martinez is fascinated by the intricacies of the human body. Her current project, “Nothing in Stasis,” comprises a series of large-scale paintings of family and friends that explore the confluence of body, mind, and spirit. If you happen to be in Arizona, the Tucson Museum of Art is hosting an eponymous exhibit through April 23. But not to worry: You can also view the “Nothing in Stasis” collection on her website.

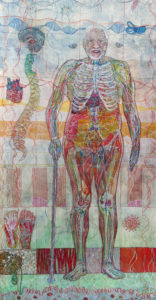

At first glance, the paintings vaguely evoke those life-size anatomical posters from high school biology class with the various systems — digestive, nervous, reproductive — mapped out.

But there the resemblance stops. In place of the featureless faces and soulless internal organs from high school, Martinez’s paintings are intricate, whimsical, detailed, colorful: gold, seashell pink, blood red, pale blue, spring green.

They incorporate flowers, ferns, fruits, vegetables, animals, symbols, myth. They’re emotionally intimate. They evoke a sense of wonder, mystery, and awe. They consider emotional, physical, and spiritual suffering.

Martinez reflects upon the concepts of feminine and masculine, horizontal and vertical, reason and emotion. Her work is steeped in the interconnectedness of all living things.

Created with, among other materials, casein, graphite, gesso, gouache, and ink, the paintings run the gamut from new life to deterioration to death. They incorporate the geographical landscape of our memories and hearts: the streets of our childhoods; the food that whispers “home”; the ways that our “unhealthy” habits also define and shape us as fully fleshed-out human beings with compassion for our fellows.

These are portraits done with infinite tenderness, thought, concern, and care. They depict the interior of the body as the body interacts and responds to the world around it, minute by minute. They take into account that the body both inhabits and undergoes the world: is buffeted, assaulted, wounded; is subjected to interior and exterior disorders, including our own compulsions, fears, and aging.

The full-scale works include portraits of Martinez’s mother, her father, her husband, herself, a niece, and a nephew’s daughter. Altogether four generations are represented.

Her women are sturdy, strong, questing, joyful. Of “Portrait of Sara, Head in Profile, Arms Akimbo” (2017), she observes: “Leonardo da Vinci says: The human foot is a masterpiece of engineering and a work of art.”

“Portrait of Elisa, 2017-2022” depicts Martinez’s mother moving through five years of life after a diagnosis of aortic stenosis. “These days I refer to my life-size anatomy studies as narratives, consequently mapping her story continues. I add to the life-size portrait of mom — Matrilineal Lineage — a heart.”

“Portrait of Roberto, A Patrilineal Study,” dates from 2015. “Next time it shows, it will be a little different.” That was in part because Martinez’s father was beginning to exhibit signs of Alzheimer’s. He died of complications from COVID-19, just three weeks after Martinez’s brother Chacho — also memorialized here — succumbed to the disease as well.

“Constellation,” completed between 2020 and 2022 after her father passed away, includes more than 30 small studies of brain-related forms.

“My work is influenced by medical and scientific illustration (including Leonardo) as well as mystical and spiritual teaching,” notes Martinez.

“Portrait of Hailey, Newly Born” (2021) limns a baby in the womb, born during the pandemic. In shades of pink and dark red, Martinez has painstakingly painted the mother’s spine, a pair of baby footprints, and the umbilical cord. The infant’s little head is turned expectantly, as if listening to faraway music, her arms are drawn protectively to chin and — lo and behold — her own tiny anatomical systems are fully formed.

“Amy and Reed birthed a baby girl last month,” reads the accompanying commentary. “Not only were people social distancing, but hospitals were setting up new guidelines. Would Amy deliver alone? Would Reed be allowed in the delivery room?”

“Hailey entered the world on April 8, 2020, at 2:38, weighing 7 lbs. 13 oz. I guess she took control of things, making sure mom and dad were together during her delivery.

“It was a good time to be reminded that truly we have no control and also that life continues.”

While creating the series, Martinez also recorded her process in a series of blog posts that blend poetry, philosophy, and humor.

Lawson, a male toddler, is shown struggling to stand for perhaps the first time. Adult hands, one on each side, grip the little boy’s, trustingly upstretched for support. The scene “represents a particular truth to me,” Martinez notes: “Change is constant.”

“Portrait of Sophie, Trisomy 21 Study” (2017) depicts her friend Amy Silverman’s youngest child, born with Down syndrome. “I have drawn the contour of Sophie’s complete body. And as I go from part to part, I can’t help but wonder how the 21st chromosome affects each and every one of her organs.”

Without being overtly religious, these are works that draw the viewer to consider the sacredness of the human body and the mystery of all creation. Like icons, they invite deep, sustained reflection.

As museum curator Debra L. Hopkins observes, “Martinez is the magician/alchemist striving to distill impurities and transmute her subjects into gold, creating alternate worlds of cosmic scope and microscopic intimacy.”