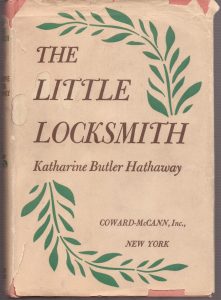

“The Little Locksmith,” a singular and mysterious memoir, was published in 1943 by a woman named Katharine Butler Hathaway.

The New York Times reported, “It is the kind of book that cannot come into being without great living and great suffering and a rare spirit behind it."

Hathaway herself called the book a “story of the liberation of a human being.”

Born in Baltimore in 1890, she spent the better part of her youth in Salem, Massachusetts. At the age of 5, she developed spinal tuberculosis. In an effort to avert kyphosis (colloquially, hunchback), her doctors strapped her for the next 10 years to a bed pulley-rigged with iron weights.

It was here that, unable to move her body or head, she honed the interior life of the imagination that would nourish and validate her later calling to be a writer.

Her family was cultured, loving, and creative (although, typically New England-ish, they were also extremely emotionally closed down, to the point that nobody once, ever, referred to her condition or uttered the word “hunchback”).

She developed a deep inner life of the imagination, encompassing both beauty and terror, that paved the way for her slow, painful, yet somehow sublime spiritual awakening.

Upon release from her bed, she was kyphotic anyway, deformed though mobile, deeply sensitive, deeply intelligent.

That she could feel passionately about an idea came, at 15, with the force of revelation. “Something had blazed in me, and from the blaze I discovered a new element in myself, a combustible something that would always blaze again in defense of the mystery and sacredness in things, and against the queer, blind, blaspheming streak in human nature which instead of adoring, must vulgarize and exploit and insult life.”

She was a “special student” for three years at Radcliffe, showed promise as a writer, underwent a kind of mental breakdown under the torment of unfulfilled romantic love, and in her early 30s, bought a house in the seacoast town of Castine, Maine.

It was a grand house, not at all the gnome-sized “thimble” she’d envisioned for someone of her size (she never grew taller than a 10-year-old).

But from the second she laid eyes on it, she saw in the house her destiny. She directed the workmen to clear the overgrown brick paths of weeds, re-install the beautifully carved old mantelpieces, switch out the “modern” three-paned windows to the traditional ten-paned variety, and repaint the original door a soft blue-green to match the shutters.

Her goal was to turn the house into a magical place where she could 1) write; 2) invite her nieces and nephews to draw, paint, dream, and play; and 3) transform the upstairs into a kind of mystic’s bordello, where men and women could come and, surrounded by tranquillity and beauty, indulge freely in the physical love she feared that, by virtue of her deformity, would be denied her.

The first goal at least was realized. She took writing as her vocation and devoted herself to it with monastic devotion, though year after year she had virtually nothing published.

She described Penobscot Bay, the light, the trees, the changing of the seasons with a poet’s eye.

“During the summers of my life,” she wrote, “it was my close-fitting, protecting shell which held only me alone. … Towards a sanctuary of this kind, or, I suppose toward any sanctuary which shelters the spirit and allows it to be free, a love develops which has a quality of deep and intimate gratitude.”

Off-page, she fell in love, married, and after 10 years left the enchanted house in Castine and moved to another in nearby Blue Hill, almost as beloved.

But “The Little Locksmith” is really the story of a conversion. Hathaway was never able to write two planned sequels. But in the epilogue, she charted the sequence of a spiritual awakening: First you look, and see beauty. Then you admire, which leads to gratitude, which leads to humility, which naturally leads to “a feeling of wonder and adoration toward the source of these miracles, the God who made them and put them there.”

Prayer “is the natural expression of those who are not so stupid and so rude as to have forgotten that they are guests. Those naïve, medieval people — and they exist always in every generation, usually obscure, unknown, and even ignorant — who begin and end each day in that most beautiful instinctive human attitude, the attitude of the sensitive, courteous guest of God, on their knees with the head bent down before an ever-present God toward whom their hearts open like drooping flowers or like radiant flowers — they are the only people who really understand admiration and gratitude.”

This is a memoir for people who have felt they might die of loneliness, or who sense that they are in some way mutilated, or who love the world but can’t quite seem to find a place in it. In other words, this is a book for all of us.

Hathaway died on Christmas eve in 1942. “The Little Locksmith,” which she called her “bread and butter letter to God,” was published the following year. It was her only book.