A journalist’s account of her relationship with her father weaves in and out of physical — and emotional — borders

For journalists who cover the U.S.-Mexico border, it is sometimes easy to forget that the story of “la frontera” is best told not in the language forged by international boundaries, barbed wire, or cross-border commerce.

It is a tale best told in terms of people, flesh-and-bone human beings who live on both sides of the border and whose lives spill out on both sides of the line.

These border dwellers include Jean Guerrero, her sister, mother, and father.

San Diego-based journalist Guerrero is, in her day job, a reporter for a local public television station who covers the border and finds herself neck deep in stories about ordinary families facing extraordinary challenges.

Guerrero also writes. She’s not a television person who writes, but a writer who does television. Her writing is good enough to have earned her a Masters of Fine Arts in creative nonfiction, and good enough to have gotten her a writing job at the Wall Street Journal in Mexico City.

Her writing is good enough to have produced a critically acclaimed first book about the tortured relationship with her father, “Crux: A Cross-Border Memoir” (Penguin/Random House, $16), and good enough to have won the 2016 PEN/Fusion Emerging Writers Prize.

And her writing is good enough to have started the prologue to her book with this strand of silk:

“I’m sorry, Papi, Perdoname. I know how much you hate to be pursued. You’ve spent your whole life running. Now the footsteps chasing you are mine.”

And to have ended it with this:

“Octavio Paz says the Mexican is the son of ‘nothingness.’ He comes of contradictions coalesced, of crucifixes and demons, of conquistadores and priests, of Cortes and Cuauhtemoc. The modern Mexican is masked mobility, fleeing from and searching for his ouroboros roots. If you succeed in catching him, you’ll find a fiction. Unmask him and you’ll find time stretching back a thousand years. …

“I’m sorry, Papi. Perdoname. I know how much you hate to be pursued. But the past has swallowed me. All roads before me lead me straight back to you.”

The Guerrero familial narrative is strewn across the border. For many Americans, the boundary separating the United States and Mexico is a closed gate. For the Guerreros, and the millions of people who live along the border, it’s a turnstile.

People come and go, every day and all day long. To work, to play, to dine in restaurants and go shopping. There isn’t a wall high enough to stop the free flow of international commerce.

If President Trump had succeeded in building his big, beautiful wall on the U.S.-Mexico border, it could be decorated with a mural telling the story of this family.

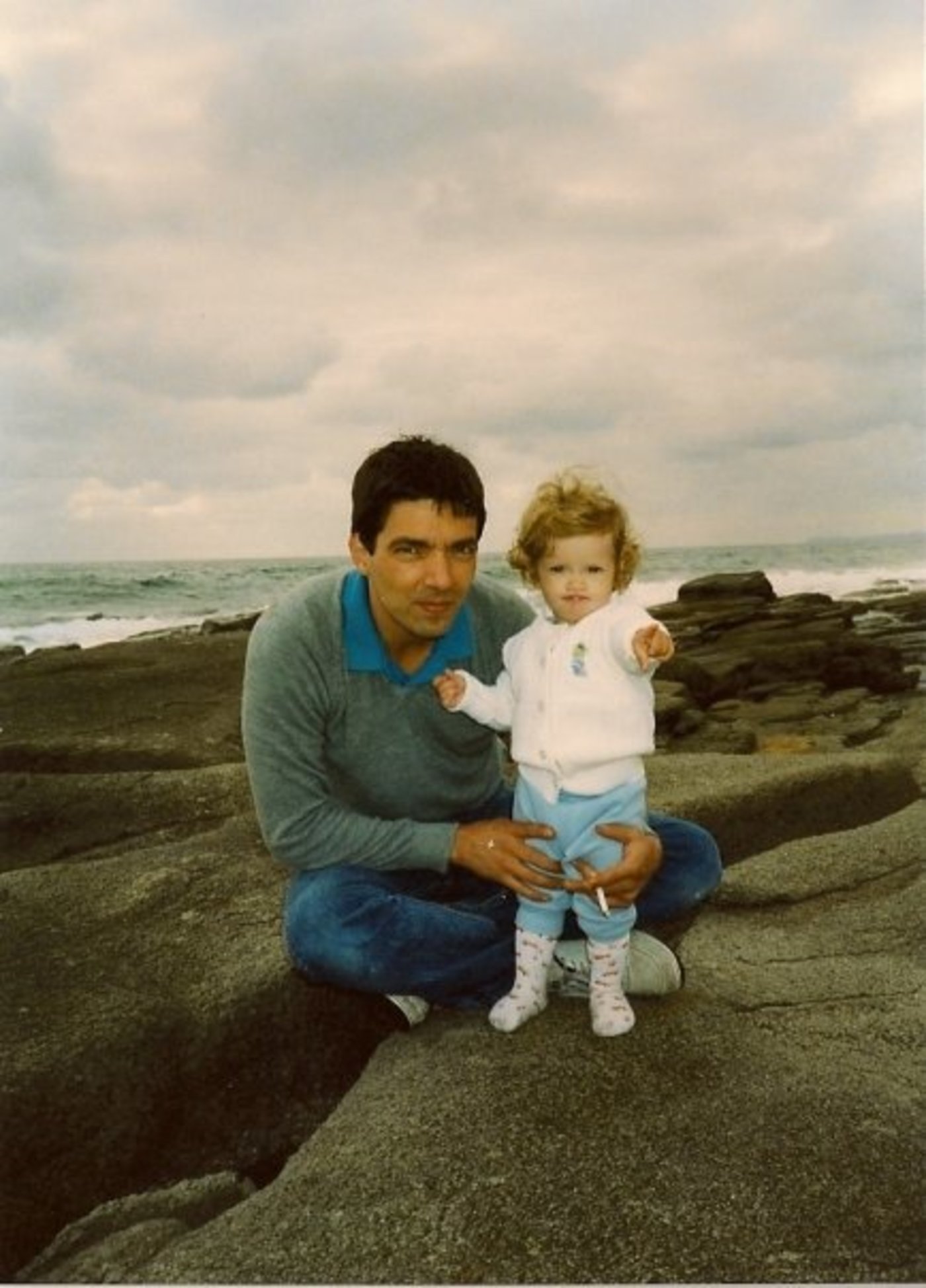

We can’t be sure who painted the picture. It could have been Jean’s mother and namesake, Puerto Rican-born Jeannette Del Valle, a physician who maintained a home and heroically raised two girls as a single mom without complaint.

Or it could have been her Mexican-born father, Marco Antonio Guerrero, a hard worker whose dreams got sidetracked by bad choices, marital infidelity, and mental illness — to the point that being a good husband and father was often beyond his capacity.

I asked Guerrero about the process of writing her book, which she started even before she began her MFA program.

“I knew it was going to be a complex book in which I would confront my lifelong obsession with my father,” she told me. “I knew it was going to be a tapestry of my family’s stories. But the MFA gave me structure and my mentors in the program kept my feet firmly planted on earth, making sure my magical inclinations didn't get the best of me.”

Guerrero originally thought the book would be about reconnecting with her Mexican heritage. It wasn’t. Not really, though it did bring on an epiphany or two along those lines.

“My story speaks to the diversity inherent in the Mexican-American experience,” she said. “There is no single Mexican-American experience. We are as diverse as America itself.”

She also thought she might discover that her father was this grand mystical figure whose wacky and wicked ways made sense in a greater scheme. But things didn’t work out that way.

“Writing this book as journalism helped free me of my father and his world of fantasy,” she said.

“In high school and college I thought of writing a work of fiction inspired by my father. When I moved to Mexico and discovered my family history was so rich with magic and mystery, I decided to write it as nonfiction. It was a great decision because it was necessary to the process of disentangling myself from my father.”

The disentangling has taken years. In fact, it seems — from reading the book and talking to the author — the process continues to this day.

Guerrero told me that her father attended a book signing in San Diego, but he sat in the back and hoped no one recognized him. And he hasn’t read the book yet, although one imagines he is immensely proud of his daughter for writing it.

This daughter-father relationship is more complicated than most, and the book doesn’t make it any less complicated. Before Guerrero could hope to define her relationship with her father, she first had to first define him. And that wasn’t easy.

“To label someone is to metaphorically imprison them within the boundaries of our preconceptions,” she said. “When I sought one answer to the mystery of my father, I was trapped in a self-fulfilling prophecy. If we stop thinking of people as categories, we start interacting with them as evolving humans.”

As Guerrero learned, interacting with family members is about taking the good with the bad and recognizing that even flawed individuals are redeemable.

“Once I accepted my father as a mix of contradictory things, both positive and negative, I realized I didn’t have to follow his path or reject him,” she said. “I could just accept him as this complex changing person, cherishing the gifts he gave me while letting go of the destructiveness.”

Guerrero also cherishes her mother, and many of those who gather at book events wonder why she didn’t write a book about that heroic figure in her life.

“The truth is my relationship with my mother is even more complicated than my relationship with my father,” she said. “And I don't think I could even begin to explore it through the page until I have children of my own. I discovered my feminism and the amazing strength of the women in my family –– and myself –– through my journey in pursuit of my father.”

Another theme running throughout this book is the concept of borders — both literal and figurative.

“My father was always crossing borders,” Guerrero said. “Between substance abuse and sobriety, between madness and sanity. My father as the ultimate migrant introduced me to the border as a metaphor. He gave me my impulse to push beyond the boundaries of the known.”

I wondered what others made of this, particularly those who — like Guerrero — grew up on the border, or who live there now.

“Readers who have reached out to me are moved by the fluidity of my life,” she said. “So many people growing up in the United States, especially along the border, don't believe they belong to a single or fixed world and have told me that the book gave them a space where they belonged: in a state of flux.”

I was curious about another relationship — between Guerrero and Catholicism.

“I was raised Catholic but quickly became suspicious of the stories I was hearing,” she said. “I no longer believe in the superiority of one religious text over all the others. I believe every religion has something beautiful and interesting to offer, whether it’s Catholicism or Sufism or Hinduism. But I do have faith in a greater power, which I can sense when I meditate.”

What about on a more personal level, I asked.

“My grandmother's Catholicism has always given me an aesthetic and emotional pleasure,” she said.

“When she blesses me with the sign of the cross, I feel safe and at peace. I talk to and think about God often, but I don't see God as an entity that commands and judges. I see God as an entity that communes and learns and expresses itself through us. I do feel God’s presence in my life constantly, especially when I’m writing, and I feel a sense of protection innate to its presence.”

It was only right to end the interview where it began — asking about her father. I wondered what the experience with her father — imperfections and all — taught her about the concept of redemption.

“My experience with my father taught me that when you ignore, repress, or hide from the mistakes you or your loved ones make, life becomes twisted,” she said.

“When I was a little girl my mother repeatedly told me to forget about my father. Obediently, I tried to erase him from my mind. So naturally, I eventually became obsessed with him. When I actually looked at him, and saw him, I was able to free myself of the prison of his patterns. That meant forgiving him. I could hold him accountable without throwing him away. I don’t believe everyone deserves forgiveness. But in my case, forgiveness was liberating.”

We can plainly see that. And when Guerrero was freed, so was her ability to tell a compelling story worth hearing.

Ruben Navarrette is a contributing editor to Angelus and a syndicated columnist with The Washington Post Writers Group and a columnist for the Daily Beast. He is a radio host, a frequent guest analyst on cable news, and member of the USA Today Board of Contributors and host of the podcast “Navarrette Nation.” Among his books are “A Darker Shade of Crimson: Odyssey of a Harvard Chicano.”

SPECIAL OFFER! 44 issues of Angelus for just $9.95! Get the finest in Catholic journalism with first-rate analysis of the events and trends shaping the Church and the world, plus the practical advice from the world’s best spiritual writers on prayer and Catholic living, along with great features about Catholic life in Los Angeles. Subscribe now!